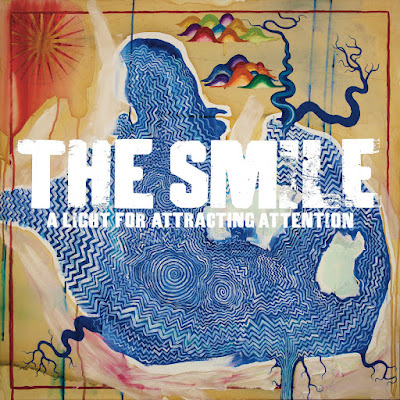

Album Review: The Smile - A Light for Attracting Attention

Am I the same person I was six years ago?

And this is not a question I have asked myself regularly, but I have found it is a question I have been pondering, off and on, as of late.

I have found myself thinking about the distance between who we are now, who we were at another specific point, and the time in between.

Six years ago, I still wrote for the newspaper—a job I would, somehow, hold onto for two years, and in May of 2016, I was three months away from finally finding my way out. Within the distance that has formed between whom I was then—stuffed in a cubicle and huddled in front of a small, antiquated computer, and who I am now, I can retrospectively describe my time at the newspaper as not the “worst job” I have ever held in my adult life; a more accurate description would be that it was a bad situation, overall, for me to have found myself in. There is a difference between being someone who likes to write, or can write, or touts themself as a writer, and someone who is a reporter, and has an interest in all the responsibilities that come with “reporting,” and the longer I found myself stuffed in a cubicle and huddled in front of a small, antiquated computer, the more I realized the responsibilities of the job were the thing that I was simply not cut out to do—or, at the very least, do well.

Am I the same person I was six years ago?

Six years ago, we still lived with a companion rabbit—Annabell. We had adopted her and her sister Sophie four years before that, and Sophie unexpectedly passed away in the winter of 2015. We would get another two years with Annabell—almost exactly two more years, before the slow and sad decline of her health that lasted from the beginning of April until the end of May of 2018, when we entered the beginning of a long year of living in silence.

Am I the same person I was six years ago?

My beard, a lot longer at this point because I did not interact nearly as much with the public, was still a blend of black, brown, and strangely, red hairs that covered the bottom half of my face; now, those browns and reds have been replaced with various shades of gray. The strange health problems I began having, more than likely brought on by how stressed out I was working for the newspaper, eventually went away—only to be replaced by different and much more severe health problems1 that will, more than likely, remain with me for the rest of my days.

I both am, and am not, the same person I was six years ago.

And I often do this—I associate a specific time in my life with an album, and as I have been thinking about the time and distance that forms between these two points, six years apart, from my own life, I have also been thinking about the time and distance that has developed between the release of A Moon Shaped Pool, the last studio album that (as of right now) Radiohead has released, and A Light for Attracting Attention, the debut full-length from the Radiohead-adjacent group The Smile.

*

And this would have been a joke I began making in more recent years, but there are times when it seems like Thom Yorke would rather do anything—score a film, release a solo album, start a whole new band—than write and record another Radiohead record.

I presume this is a well-known fact, or at least well-known for people who have spent almost 30 years of their life listening to the band, but Radiohead’s recording sessions—specifically from, like, OK Computer through Kid A and Amnesiac, were fraught with tension; as were the original session for In Rainbows, which were going so poorly at one point that someone within the band’s management suggested that, rather than continue to toil away in the studio on something that seemed to no longer be working, the group should simply break up.

A band like Radiohead has never cared what expectations might have been placed on them, and that shows in how, at least since the release of OK Computer, they’ve abandoned the idea of a predictable album cycle—five years passed between the release of the maligned, experimental The King of Limbs, and the arrival of A Moon Shaped Pool. In the space, and distance, that has formed between that album, and this new project, The Smile, which features two out of the five members of Radiohead—that band, as an institution, has opted to lean into the celebratory nostalgia that comes along with the milestone anniversaries of some of their most important work—releasing the impressive and comprehensive OKNOTOK reissue package in 2017, and the slightly less impressive and not as comprehensive Kid A Mnesia at the end of 2021.

Outside of Yorke’s penchant for staying busy through other creative projects—either on his own, or with other collaborators, almost everybody in Radiohead has also gone onto some kind of solo endeavor, save for the group’s subdued bassist, Colin Greenwood. His brother, lead guitarist Jonny, has become a go-to composer for film scores, and worked with the Indian music group Rajasthan Express in 2015; drummer Phil Selway also has dabbled in film scoring, and released two folksy solo LPs; and the band’s underrated and perhaps under-appreciated guitarist Ed O’Brien was the most recent to pursue a project outside of the group, recording the album Earth, under the moniker EOB, which was released shortly before the onset of the pandemic in early 2020.

I get the impression that the five members of Radiohead, along with their unofficial members—regular producer Nigel Godrich, and visual artist Stanley Donwood, do not hate each other. But nearly 30 years after the success of their angsty single “Creep,” I wonder what the dynamic within the band is like now—if, after all that time, it’s less “fun” and more like a chore or like work. Maybe it isn't easy to coordinate that many people's schedules with whatever other responsibilities or endeavors they respectively have. Perhaps some members of Radiohead, outside of the band, need to remain creative through additional projects, while others are completely okay with taking a break from performing.

Maybe six or more years need to pass between the band they were in 2016 and the band they might be whenever it is they reconvene.

Famously, especially the further in their career they’ve gotten, Radiohead’s music—specifically, I guess, Yorke’s lyricism—has become more and more fragmented and ambitious, where it is a challenge to know or surmise, what the meaning of a song is if there is one to be gleaned. However, if you listen to A Moon Shaped Pool through over-analytical ears, and understand the context around the album, there is a sense of both finality and uncertainty that looms heavily—it is speculated to be an album that, at least in part, is a reflection on the dissolution of Yorke’s marriage to Rachel Owen2.

And I mention A Moon Shaped Pool not only because of the space that has formed between its release, and today—the space that has formed in between who I was in 2016 and who I am today, or who Thom Yorke and Jonny Greenwood3 were then, and who they are now, but because, in working with jazz drummer Tom Skinner and pairing once again with Nigel Godrich as producer, this debut as The Smile seems, at times, to live underneath the shadow of A Moon Shaped Pool, at least musically speaking, all while attempting to outrun it.

This is neither a good nor bad thing—it is just an inescapable detail of A Light for Attracting Attention, and perhaps to an extent, something unavoidable that happens when two members of a long-running group launch a new project together. There are traces of familiarity throughout the album in the form of similar chord progressions, guitar tone and playing, and of course, the sound of Yorke’s voice. The group—taking their name from a Ted Hughes reference and, as Yorke put it, not “the smile as in ha ha ha; more the smile of the guy who lies to you every day,” spend the album’s run time working within a space they know well, while still trying to push themselves forward within a different identity—through moments of smoldering tension followed by dizzying and chaotic bursts of release.

*

The thing that is, perhaps, the least surprising is how effortlessly the group manages to blend specific elements in creating the aesthetic that runs throughout the album. Outside of the similarities to Yorke’s and Greenwood’s day job, Skinner brings an impressive heft and control of rhythm to his work behind the drum kit. At the same time, Greenwood’s dramatically composed and often sweeping orchestral arrangements punctuate the songs they are included in with a theatrical flair. Yorke’s long-running interest in electronic music can be heard in the warmth of the myriad vintage synthesizer textures and the jittery, frenetic energy a handful of these songs are built around.

The thing that is, perhaps, the most surprising is the album’s two most brash, ramshackle songs—the penultimate “We Don’t Know What Tomorrow Brings,” and the band’s debut single, which was released at the beginning of the year in slow rollout leading up to A Light for Attracting Attention, “You Will Never Work in Television Again.”

The word “punky” is the first word that came to mind when hearing both of those songs within the album's context as a whole—and across A Light’s 13 tracks, they are the only two constructed with that unhinged energy. They don’t sound like they are on the verge of falling apart at any moment, but there is a sloppiness and exuberance within each song—both within the music and the way Yorke sneers his way through the vocals, that is refreshing to hear.

“We Don’t Know What Tomorrow Brings,” tucked near the very end of the album, is like a final gasp or exhale before the slow-burning conclusion that comes immediately after—propelled forward by a thick, rolling bassline and unrelenting rhythm, the song rides a kind of post-punk energy while layers of buzzy synths cascade and ripple throughout.

Radiohead is not exactly a band whose sound you would describe with words like “snaring” or “ferocity”—in their early days, maybe, and the two most recent songs that come close would both be from the In Rainbows sessions (“Bodysnatchers” and “Bangers & Mash.”) And much like “Bodysnatchers,” which at times, seems like it’s moving just so quickly that it might get away from the band’s grasp, “You Will Never Work in Television Again” tumbles along with a kind of attitude where if it does go off the rails, the group wouldn’t care—because, at least in this case, maybe that’s the point. The bass guitar chugs along with reckless abandon while Skinner punctuates the emphasis of Yorke’s shouted lyrics with aggressive cymbal crashes.

And equally, if not more surprising than “Television”’s brazen arranging, are the song’s lyrics, which find Yorke crafting a narrative that appears to be about a Harvey Weinstein-esque media figure and the damage their abuse has caused. “Fear not my love, he’s a fat fucking mist,” Yorke begins, literally barking the words out. “Young bones spat out, girls slitting their wrists. Curtain calling for the kiss—from some nursery rhyme, behind some rocks, underneath some bridge,” he continues before making the song’s antagonist clear. “Some gangster troll promising the moon.”

“You sad fuck, you throw small change. Take your dirty hands off my love,” Yorke slurs near the song’s ending.

*

Across an album with so many different influences and aesthetics, the very notion of there being contrasts is expected—the way those contrasts are used, though, is impressive in their intelligence.

A Light opens with songs entitled “The Same” and “The Opposite,” and in just glancing at the tracklist, seeing those sequenced back to back garnered a chuckle in terms of The Smile’s apparent self-awareness—but I think that’s the point, or at least part of the point, in placing those songs next to one another.

“The Same” is among the songs on the album that relies heavily on layers and layers of warm synthesizer tones, and of those five or six songs, “The Same” is one of the most chaotic—creating a deliberately paced rise in tension and noise. Featuring no percussion, and just some subtle electric guitar accompanying in the mix, the different tones and sounds begin bouncing in, then continue to restlessly shift around and oscillate within the boundaries that the band has set, which continue to grow and create an ominous, swirling cavern of noise as “The Same” continues.

That glitchy, chilling opening is juxtaposed against Skinner's crisp, precise jazz drumming, which kicks off “The Opposite”. This tune slithers and writhes along to a deep bass groove and intricate, hypnotic electric guitar work, operating from within a tone that echoes with familiarity.

The Smile repeats this juxtaposition in extremes with the next two tracks—the wild “You Will Never Work in Television Again,” which careens into its conclusion like a car slamming into a brick wall, which is followed by the unnerving, creeping piano intro of “Pana-vision,” one of the slower burning songs on the album, and the first one to borrow heavily in its arranging and progressions from the sounds of A Moon Shaped Pool.

There are no places on A Light for Attracting Attention where The Smile is unsuccessful in creating a song, but it is the spots where things are unpredictable that are the most successfully executed and among the most memorable—like the wildly flailing exuberance of “You Will Never Work in Television Again,” which, by releasing it as the album’s first single, is not exactly an inaccurate representation of the project as a whole, but I truthfully was, at least until the next advance single arrived, hoping the entire record would sound that visceral.

As A Light for Attracting Attention moves into its second half, you can hear more of the dense and slippery textures that are similar to Yorke’s interest in electronic music and his output of three solo LPs over the last 16 years—but before the slithering rhythms and the walls of keyboards become more prominent on this album, a song like “Thin Thing” serves as a bridge between the thrashing chaos of a track like “You Will Never Work in Television Again,” and the more electro-infused and manipulated songs that arrive after the halfway point.

“Thin Thing” is powered by a dizzying display of guitar theatrics from Greenwood—there are no videos online yet of him actually playing the progression that opens the song, but enough YouTubers have, since the album’s release, wasted no time in trying to unpack just how the sound is being created—more than likely through the use of a delay pedal, while quickly plucking the strings and muting them with your palm to get that spiraling, bouncing effect; Skinner, from behind the drum kit, is able to find his way into the song shortly after it begins, while Yorke, in delivering his vocals, lets them become warped and distorted in various ways, at times losing control of the sound completely.

“Open The Floodgates,” in a sense, also serves as a bridge between Yorke’s interest in synthesizers and ethereal tones, and the more dramatic, slow-burning progressions from what could only be called Radiohead’s “ballads”—the sweeping, emotionally stirring, and piano-driven tunes, like “Pyramid Song.” “Floodgates” is surprisingly effective and beautiful in the way that the jouncing synthesizer tones weave themselves into the spaces form between the chords on the piano. It, like “The Same,” is without any percussive elements, and in a way, it is the antithesis of the chaos created within “The Same,” as all the keyboard layers converge into one another and create a cacophony; there is no collision on “Open The Floodgates”—just gorgeous and gentle drifting.

Of all the members of Radiohead to pursue solo endeavors, Yorke, famously, was the first, releasing The Eraser in 2006—to tour the songs from that album, Yorke formed the “supergroup” Atoms for Peace alongside Nigel Godrich and the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ bassist Flea—following the tour in 2010, the group spent an extended weekend jamming. Then Yorke and Godrich spent two years, off and on, editing and manipulating those sessions into an Atoms for Peace full length, Amok, released at the beginning of 2013.

Even in the similarities between Atoms for Peace and Radiohead (Yorke’s voice, mostly), it was easy to hear the apparent differences in the projects because Atoms for Peace, outside of a drummer, also included a percussionist, who provided additional rhythmic textures, and gave the album an “Afrobeat” kind of feeling.

Again, this time with Greenwood and Skinner, Yorke steers The Smile’s debut into Afrobeat influence on the kinetically energized “A Hairdryer.” The song opens with a simmering rhythm from Skinner’s kit, with muffled, cavernous reverberation off of the drum hits in the distance, which is among one of the more impressive production details across the board on this album. From there, “A Hairdryer” begins to swirl around with chaotic, conspicuous momentum that never lets up until there is a minute left in the song, when the percussion stops, and the song doesn’t come to a screeching halt, but dumps the listener into a wave pool of tension created by various sustained drones that continue to eerily build and ripple.

*

Someone lead me out of the darkness

I hesitate to refer to Yorke’s lyricism throughout A Light for Attracting Attention as taking a backseat to the instrumentation and dynamic arranging, because they don’t. Still, as heavily cloaked in ambiguity as they might be at times, his phrase turns can often subtly surprise, slowly lingering or resonating with the listener.

Perhaps the most surprising element of the lyrics on this album is Yorke’s utterances of profanity. “Somebody’s falling down,” he sings in “The Same.” “Somebody’s telling lies. Simple-ass motherfuckers with one mistake after another.” Then, shortly after on “You Will Never Work in Television Again,” he refers to the song’s vile antagonist as both a “fat fuck” and a “sad fuck,” which in the context of the song’s construction, only adds to the punky, brash energy of it all.

The winking, somewhat self-aware lyrics from “Open The Floodgates,” remind listeners of Yoke’s extremely dry, subtle sense of humor. In this case, it’s his take on what audiences and listeners might want, which might not be what they will get: “Don’t bore us—get to the chorus,” he croons over the mournful piano chords and twinkling synthesizers. “And open the floodgates—we want the good bits without your bullshit, and no heartache.”

As oblique as Yorke can be, there are hints or at least speculation that a lot of the song’s fragmented lyrics are politically inspired—the apparent humor in the title “A Hairdryer,” and reference to the “blue-eyed fox” could allegedly4 be a reference to either Donald Trump or Boris Johnson, while other songs, like “The Smoke” detail Yorke’s ongoing anxiety about climate change, as does A Light for Attracting Attention’s final piece, “Skrting on The Surface.”

“Skrting,” is perhaps the oldest song included on the record—a fragmented lyrical link within the song dates back as far as Radiohead’s writing and recording of OK Computer, and the song itself, was performed during Radiohead’s 2012 tour in support of The King of Limbs, as well as during the Atoms for Peace tour a few years prior.

While there are surprising flashes of hope or optimism in various pockets of the record, “Skrting on The Surface” is the starkest and bleak in its simply stated observations—and in being somewhat musically restrained, it is a slightly unceremonious and unsettling note to end on. “When we realize we only have to die, then we’re out of here—we’re just skirting on the surface,” Yorke reflects somberly. “We have only to click our fingers and disappear.”

His musing becomes more despondent as the song continues into its second verse, and the chorus. “We realize we are merely held in suspension ’til someone comes along and shakes us as the pattern lines cross our fingers like a web—do we die upon the surface?, he asks; then, in the end, as much acceptance as once can have. “When we realize that we are broke and nothing mends, we can drop under the surface.”

*

And perhaps it is the pensive, melancholic in me—A Light for Attracting Attention is an excellent, dense, and often thought-provoking album from beginning to end, but of the album’s 13 tracks, there were two that stood out immediately, for me, as its most delicate moments: “Speech Bubbles,” which arrives near the halfway point, and one of the last advance singles issued before the release of the entire album, the brooding and swooning “Free in The Knowledge,” both of which are the most pensive and melancholic of this set.

“Speech Bubbles” shuffles along somewhat gently, with Skinner’s lightly brushed percussion tumbling in and finding its place against an extremely mournful sounding organ drone. From there, dramatic strings creep in, as does the trademark Greenwood/Yorke electric guitar noodling, tonally reminiscent of both tunes from In Rainbows and A Moon Shaped Pool.

And this, perhaps, is the place to discuss Yorke’s voice, and how it has aged, and aged well, since the world at large was introduced to his otherworldly howl in 1993 on “Creep.” Now in his early 50s, Yorke’s voice still has a lot of the range it did in his youth, but you can tell that he uses the extremes it can reach with care. There are places on A Light, like “Speech Bubbles,” for example, where he rises to a higher register, but does so with reservation—his voice doesn’t break, exactly, but when he pushes it into this place, you can hear the fragility of it, and this creates one of the more honest and human moments on the record.

Allegedly about child refugees5, there is a sense of desolation and hopelessness as Yorke paints an ambiguous but incredibly evocative portrait with his lyrics on “Speech Bubbles.” “Devastation has come,” he begins in the song’s only verse. “Left in a station with a note upon6, now there’s never any place to put my feet back down…but I lie to myself,” he continues, “Anywhere I dare put my feet back down.”

And set against the gorgeous swell of music that envelops the song, there is even bleaker imagery in the song’s bridge, and its closing moments, as Yorke asks, “Who’ll find a cab in the pouring rain? Who’ll find a vein to put the needle in? How will I know you?”

If Yorke’s voice, and the way he can still impressively work with it, despite the apparent aging that has occurred as gracefully as it has been able to, becomes one of the more human moments on the record, it is the song “Free in The Knowledge” that is the most human, and stunning, of them all.

Opening in the similarly glacial way that Radiohead’s “How to Disappear Completely” does with a stirring undercurrent of strings, and a strummed acoustic guitar, “Free in The Knowledge” is, at its core, Yorke reflecting on mortality, or at the very least, what time does. And unlike “How to Disappear,” which continues to swirl for, like, over five minutes in a place of unnerving, gorgeous tension, there are shifts between resolution and minor dissonance throughout “Free,” like when the intro to the song moves into the first verse, then the verse moving into a noticeably different tone within the chorus, and with the devastating final lyrics.

And it is not that I wasn’t looking forward to the full-length LP from The Smile after the band began rolling out singles at the beginning of 2022—I was truly surprised it was arriving so early in the year7, actually, but it was the release of “Free in The Knowledge” as one of the final advanced tunes issued before the album in full, that solidified my belief and enthusiasm in the project.

Radiohead has been my favorite band since I was in junior high—and I will admit that their music isn’t always accessible to a casual listen. An anecdote I often think of, when sitting down with a Radiohead record and hearing something that still, after 20 or more years, moves me, and reminds me why they are my favorite, is when I was in college, seen regularly wearing a Radiohead t-shirt around campus, there was a young woman, two or so years younger, that made it a priority to antagonize me about what music I was listening to, or liked, and what band was on my t-shirt that day. She, apparently, believed that nobody actually liked Radiohead, and that they were a band that people just said they liked, or wore the t-shirt of, to make themselves appear more intelligent or like they had better taste.

The formation of The Smile is not exactly shrouded in mystery—how Tom Skinner became involved as the group’s drummer, though, I am uncertain. In the Wikipedia entry for The Smile, Greenwood is quoted as saying the project became a way for him and Yorke to work on music together, as they were able, during the early stages of the pandemic and lockdown in 2020, and the trio officially debuted as a band during their virtual “in the round” live performance filmed for the Glastonbury festival last year.

The pandemic, and the anxiety it has caused, does not weigh heavily over the songs that were recently written for the project, but it does cast a shadow here and there, specifically in the album’s opening track, and it is difficult not to take Yorke’s reflections on mortality and change from “Free in The Knowledge” as thoughts that are inescapable from rumination over the last two years.

“Free in the knowledge that one day this will end,” he begins. “Free in the knowledge that everything is change.”

The beauty in the song, or at least the humanistic fragility, comes in the way Yorke lets his voice rise and begin to shatter in places on the song’s chorus—“If this is just a bad moment and we are fumbling around, but we won’t get caught like that—soldiers on our backs…” And whatever kind of tenderness comes through in that reflection evaporates in the sobering and effacing lines that take the song to its ending—“I talk to the face in the mirror but he can’t get through. I said, ‘It’s time that you deliver; we see through you.’”

*

I left my job near the end of last year—the position that I held for over five out of those six years that formed in the space between whom I was in the spring of 2016, listening to A Moon Shaped Pool, and the person that I am now, sitting with and thinking about A Light for Attracting Attention.

Part of the thing that kept me at that job for so long—specifically within the last few months, was that I didn’t have any prospects for something new to jump directly into, and I grappled a long time with a lot of anxiety about the uncertainty of not knowing what was going to come next—and when that something was going to come along.

Once I gave notice, though, and word got out that I was leaving, a number of my co-workers started to ask me what my plans were. Outside of finishing my end-of-year writing and wrangling podcast guests for 2022, I told them I would focus on my mental health more than I already had been, and try to “be kinder to myself.”

But as the year ended, and another one began, what I found was telling people I was “kinder to myself” was bullshit, because the truth was, I had no idea how—no idea how to give myself any kind of grace, or cut myself a break with literally anything.

And the reason I even bring this up—and it might not have even been the first time I listened to the song, but there is a feeling that still resonates within when I hear Yorke’s voice stretch the syllables out and sing the line, “If this is just a bad moment,” because I think about all of my own “bad moments,” the bad days, or the sad days, or the grace I am unable or unwilling to show myself.

We are fumbling around.

I think about how everything is change.

I think about how one day, this will end.

I think about who I was six years ago, who I am now, and the spaces that form in between that time and distance and how, regardless of how similar or different I am now to who I was in the past, the thing that we both share, especially using these specific points, is we are both in bad moments.

The straightforward way out of this piece about The Smile is to say that if you are a fan of Radiohead, you’ll like this album—but that isn’t necessarily true. And it might be impossible—at least for me, to try to separate The Smile as being just an album—just another album by just another band, and not an album made by two people who also happen to be in my favorite band.

For the Radiohead fan—the casual one, or the one who doesn’t really listen but says they do to sound more intelligent than they are, or that they have better musical taste than they do, there are enough similarities between the two projects that will make it an appealing listen, but there are also enough differences between the two projects that some might not connect with it, or might turn listeners away completely.

I did not go into A Light for Attracting Attention thinking that I would dislike it, but I am surprised at how much I did, almost immediately like it as a whole—less glitchy and exponentially more thoughtful than Yorke’s post-Eraser solo albums, as well as his Atoms for Peace LP, it takes something familiar that someone like myself holds incredibly dear, but there are enough differences to make it a refreshing and often thrilling album to spend time with.

The last lines of “Free in The Knowledge” are, “I talk to the face in the mirror but he can’t get through. Turns out we’re in this together—both me and you.” It’s a little cloying—maybe more cloying than someone might expect from Yorke’s lyricism, but it is one of the few flickers of hope or optimism to be found on A Light for Attracting Attention—hope and optimism that are perhaps difficult to accept, but are needed.

1- Three years ago I was diagnosed with a bulging disc in my lower back. It’s the kind of thing that there is no “cure” for—much like depression, I guess. I am just supposed to find ways to manage it as best as I can.

2- For a long time, it was believed that Yorke and Owen were just long-term partners, but it was reported, at some point, that they had “secretly” married in 2003. They allege their separation was amicable, but there is something about their relationship ending in 2015, A Moon Shaped Pool’s big “divorce album” energy the following year, then her death a few months after the album’s release never really sat well with me.

3- There was no way for me to shoehorn this into the piece, but I recently read something about Jonny Greenwood being both anti-vax, and transphobic. I am uncertain if there is any truth to either of these, but these do not sit well with me either.

4- I say “allegedly” because this is speculation from the user-submitted annotation on Genius.

5- See above footnote.

6- I had a brief moment while writing this where I wondered if this lyric was about Paddington.

7- The album was finished as of early January, but according to the Instagram post updating folks on the fact that the album was, in fact, finished, it is mentioned the band had yet to decide the final running order for the songs. Because of “peak vinyl,” some smaller labels and independent bands are, in some cases, looking at almost a year turnaround to get LPs manufactured; however, it seems to be well known now that larger labels with more money to throw around are budging in line at pressing plants, so that “big” releases can arrive in a timely manner on vinyl. Even with there being a month between the digital release of A Light for Attracting Attention and the physical editions arriving, I am surprised at how quickly this album has materialized, and maybe more than surprised, I am possibly disappointed if XL Records muscled some indie label or band out of the way to make this happen sooner.