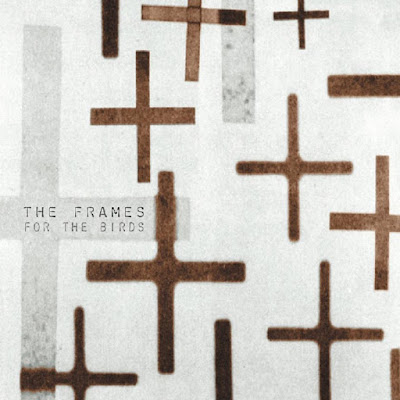

Dissimulate and Celebrate This Time We Had Alone - The Frames' For The Birds turns 20

Even though it was released in the spring of 2001, and is among the albums celebrating that milestone 20th anniversary this year, I do not associate The Frames’ career defining fourth full-length, For The Birds, with the year 2001.

I associate it with the summer of 2004.

That was the summer I turned 21—and as a birthday gift, my friend Kate gave me a copy of the book Radio On, published in 1997, and written by Sarah Vowell. In it, Vowell documents her experiences listening to the radio—alternating between rock stations, talk radio, and National Public Radio—for an entire year.

The book was written throughout 1996, and in reading it, it was the first time (to my knowledge) or at least the first time that I can really recall doing this—but while reading it in my sweltering dorm room—a hot, humid Midwestern summer spent living on campus between my junior and senior years in college—it was the first time I began thinking about where I was, or what I was doing in my life during the period of time Vowell had immersed herself in the airwaves and writing about what she heard and how it made her feel.

In 1996, I was all of 13, finishing seventh grade and going into eighth. My mother, barely a year outside of her divorce from my father, remarried—a friend of the family, who had lived up the street from the house I grew up in.

A friend of the family—and, for a number of years, was once a colleague of my father.

The man she remarried was around 20 years older than she was, and he had a handful of adult children—the youngest, at the time, was 21. And while reading Radio On, and thinking about where I was, and who I was, in 1996, I thought about something that I, somewhat surprisingly, often return to, which was how a few of his adult children were very kind, and very patience with their newly inherited teenage stepbrother.

The youngest, David, watched “Space Ghost: Coast to Coast” with me, late at night on Cartoon Network and introduced me to music I otherwise would have maybe never found on my own—or would have found much, much later in life.

One of the children in the middle, Audrey, and her partner, Eileen, were generous enough to let me stay with them for a week in Chicago while my mother and her husband were on their honeymoon.

I think about where I was, and who I was.

Self-released via The Frames’ newly formed vanity label Plateau, For The Birds is a collection of songs recorded on their own terms—compiled slowly through sessions in France, Chicago, and in their home country.

Thankfully ditching the flat, antiquated production and mixing of their previous two efforts, released via Trevor Horn’s ZTT imprint, For The Birds was, in part, recorded and engineered by the legendary Steve Albini, who was partially responsible for the way this record ended up sounding—capturing the band at their most raucous and visceral.

Not that albums like Dance The Devil or Fitzcarraldo were “funny” or meant to be light hearted, but there were moments where you could hear a slight sense of humor written into some of the songs—something that, in retrospect, it is very easy to recognize For The Birds is intentionally missing.

It isn’t necessarily a dark album in comparison, but in its visceral nature, there is a starkness to it, both musically, as well as lyrically.

It’s poignant, and thoughtful—then as well as now.

In April of 2001, I was a senior in high school, not even 18 years old yet.

I was beginning to mature, albeit very slowly, in my musical tastes—already a longtime fan of Radiohead, I was easing my way into artists like Jeff Buckley, PJ Harvey, and Portishead, but because I was still a teenage boy, you could still have found albums by Limp Bizkit in my CD collection.

I think about where I was, and who I was, and if I would have first heard For The Birds upon its initial release, in the spring of 2001, what I have been wondering lately, because of the three year difference between when it was released and the time period I actually associate it with is if I would have liked it at all.

There is a part of me that wants to believe I would have—2001 was also the year I was first introduced to the Red House Painters, and then later on, a few weeks into my freshman year in college, Pete Yorn and Sigur Ros.

But there’s another part of me that is not certain, and there is really no way to know. This passing thought is simply something trivial that I have been ruminating on—while ruminating on the album in question being two decades old.

I should, of course, be grateful that it came into my life when it did.

I was introduced to The Frames in the spring of 2004, and I first truly heard For The Birds a few months later, in my sweltering dorm room during a hot, humid Midwestern summer spent living on campus between my junior and senior year of college.

*

For The Birds begins as a gentle whisper that you never really want to end, and less than an hour later, it concludes in a writhing fit of cacophony with a hidden, instrumental track, arriving shortly after the smoldering swagger of “Mighty Sword,” the “proper” conclusion to the record.

“Is there a bad song on For The Birds?”

That was a note I had written down in somewhat long list of observations and ideas to consider while listening to the album now, in 2021, with one ear still firmly pressed up against the sound of nostalgia, but the other listening intently and analytically.

The answer to that question is both yes and no.

No, there is no bad song, per se, on For The Birds.

Even when the pacing falters slightly near the middle, and spilling into the second half, there is nothing that is deemed inessential to the record’s structure. And I stop short of calling it a perfect album, or a flawless album, because of those minor missteps. But it comes close, and if anything else, it’s timeless—the kind of blistering and urgent album that still sounds vibrant and vital 20 years after its release.

But even when it does lose its way slightly, the songs are all still very listenable, and even in those missteps, or tracks there are less successful, there is something beautiful to it all—within the very raw, very live sound that encompasses the album as a whole, there is an honesty, for better or for worse, that you can still feel the ghost today.

For The Birds is arguably one of the best Frames albums (their 2004 release Burn The Maps is also a strong contender as a whole, even with a few more missteps included)—it encapsulates the sound and momentum of a band that had been slowly working toward something much larger than themselves, and before that time, they were only able to show flickers or hints of.

In the spring of 2004, I watched the five members of The Frames step out onto the stage of the Barrymore Theatre in Madison, Wisconsin—the group’s principal songwriter and frontman, Glen Hansard, standing an even six feet tall, seemed towering and imposing at first, though that quickly dissolved once he began breathlessly and nervously speaking into the microphone with his thick, Irish accent, introducing a new, and at the time unreleased song, “Keepsake,” which would be included months later as the centerpiece to Burn The Maps.

Sprawling over seven minutes in length, this is an absolutely audacious way to open up your set—and it’s even more audacious move when you are the supporting act on a tour; the Frames were tapped as the opening act for Damien Rice. And Keepsake” repeats a trick that the group originated on “Santa Maria,” the explosive song buried near the end of For The Birds. These are songs that rely on a slow simmering sense of tension that builds, and builds, until it boils over in a powerful, all encompassing release that is almost, simply, too much to comprehend.

Aside from being “another band from Ireland” who were opening up for the very sensitive and earnest (and in retrospect, toxic) Irish singer/songwriter I was at the Barrymore Theatre to see, I knew literally nothing about The Frames before they came out on stage, but by the end of those seven minutes, before they even launched into any more of their wild, unpredictably energetic, and rollicking set, I was a believer.

And to the extent that I can be, I still am.

The Frames have been more or less inactive, for a number of reasons, since 2007—releasing one new song, “None But I” as part of their 2015 anthology Longitude, and occasionally playing a commemorative one-off show in their homeland.

And friends, here’s the thing—you can choose to lose faith in a band after they’ve called it a day, whether there was an official break up, or just becoming “inactive,” or you can continue returning to those moments that made you one of the faithful, allowing those moments to provide you a reminder of why you were a believer in the first place.

There exists a Venn diagram of why I am so attached to For The Birds.

In one of the larger circles is the fact that even if I hadn’t spent the last 17 years harboring some kind of emotional attachment to it, it is simply a beautiful and volatile collection of song that as someone committed to really listening to music, I can appreciate as a marvel and high watermark in the band’s canon.

In the other larger circle would be that moment after The Frames finished playing “Keepsake,” seven minutes into their blistering, charming, tightly knit set at the Barrymore Theatre, shortly before Easter in 2004. They were so good that they, honestly, upstaged Damien Rice, whose set was jumbled and disorganized the further it went on into the night. It would be that moment of becoming a fan, then spending the rest of the year immersing myself, as I was able to, in their discography.

There exists a Venn diagram of why I am so attached to For The Birds, and there is a place where those two larger circles overlap and form a convergence. And friends, that space is the summer between my junior and senior year in college—a hot, humid Midwestern summer and this is a period of my life that I don’t think I have ever explicitly written about before in terms of why it was, in fact, so important to me, but have, on more than one occasion, written about it with vagueness and ambiguity, referring to it as a “transformative” time for me.

During this span of time, For The Birds was one of the albums that I listened to almost non-stop.

*

What I realize now, 17 years after I first heard the slow, deliberate fade of the opening, instrumental composition, “In The Deep Shade,” and the torrential squalling of “Santa Maria,” is that For The Birds, at its core, is an incredibly restless album, both literally and figuratively.

There is heartbreak, of course, as there is with almost everything Glen Hansard has written since the inception of The Frames in 1990—but it isn’t a “breakup album.” Of the 10 non-instrumental tracks on the album, roughly half of those go into detail—sometimes, quite graphic detail—of either a relationship that has already ended (and ended very badly), or one that is just about to end, though one of the parties involved is unaware of what lies in the immediate future.

If I don’t get out of this town, something’s gonna break

Set against a bombastic drum machine and tumbling, folksy instrumentation, Hansard utters that line in “Fighting on The Stairs.”

And it isn’t a conceit, or even a through line for the album as a whole, but it does, as best as it is able to, articulate that restless feeling—indicative to the underlying, completely unspoken tension the band has woven into For The Birds. Similar to the soundscape of the album, and the explosive, raw sound of the band at this time—showing flashes of The Frames working toward something much larger than themselves, there is a very palpable, urgent, immediate yearning for something more, or greater in these songs.

Musically, and thematically, the first half of For The Birds is, perhaps, its most restless, and much like the band’s live performances, it’s unpredictable in the directions it takes you. Even now, two decades after the fact, and 17 years after I first sat down with it, the ebb and flow is still surprising, as well as admirable, since even under the constant shifting tonality, the band never lets these songs get away from them, even when it seems like it could all come crashing down at any moment. The stakes are high, and I think that’s what makes it so exhilarating, even today.

As the album begins to open itself up, what I’ve realized now, listening intently and analytically, 20 years removed from its release, is that within that musical restlessness found right out of the gate on the album’s first side, there is also a restless nature within the way Hansard juxtaposes is depiction of what I can only call now a “dangerous” kind of love.

Set against rollicking, jaunty, and hypnotic drumming, “Lay Me Down,” the first track on the album to feature vocals, sounds at first like a simple, earnest love song. And it doesn’t come through on For The Birds, because of the overall stark nature of the record, but Hansard is, or can be, very funny when he wants to be, and is a natural storyteller—his in-between song banter during the band’s live shows is infamous, though it is often tough to know where the joke, or exaggeration ends, and any kind of truth begins.

It seems heartfelt enough, yes, but over the gentle plucking, and very rootsy sounding violin work by the band’s only other original member, outside of Hansard, Colm Mac Con Iomaire, there is a dark shadow cast by the inspiration to the song. Hansard’s told myriad versions of the tale to different audiences across the last 20 years, but at its core, the surprisingly macabre story behind “Lay Me Down” involves an early relationship Hansard was in with who, I believe, he described as being a girl with Gothic leanings, and his decision to buy a burial plot for her as a gift.

This is then contrasted against the devastating sorrow of “What Happens When The Heart Just Stops.”

Of all the songs about heartbreak on For The Birds, I don’t want to say that “What Happens” is maybe not the most devastating, or harrowing in its depiction of a relationship’s ending, but it is the one that leaves a spectral chill in its wake, particularly because of the way Hansard lets the last syllable of the song’s final lyric hang as the instrumentation behind him comes slowly comes to a stop—“It’s so late, ’til you’re gone.”

And if “Lay Me Down” is a glimpse at a well intended, though “dangerous” kind of love or affection, “What Happens When The Heart Just Stops” is a hard look at when one person in a relationship is not willing to come to terms with the fact that it is, simply, over. There is a danger to that, of course, as well as a terrible toxicity I only realized in time—an element to this song, and a lot of this album (and a lot of music made by “sensitive” men, if we are being honest) that did not register when I was in my early 20s, but something too difficult to ignore the older I have grown, and the further away I have not so much distanced myself from bands like The Frames, or artists like Damien Rice, but there are levels to the way you look back at music you once held fondly.

You can leave it behind with a specific time period of your life, and think of it as something you “used to” listen to, or you can try to take it with you—it can either grow with you over time, and find new ways to be impactful in your life, or at the very least, you can appreciate it for what was, what it is now, and what it meant if there is no longer space made for it.

In an introduction to a live performance of the song, transcribed on the online community SongMeanings.net, Hansard is quoted as saying “What Happens When The Heart Just Stops” is about “over feeling” when you are in a relationship; in a different introduction, he claims it is about getting blackout drunk, waking up in your ex-girlfriend’s garden, and remembering that the two of you are no longer together.

“What Happens” is one of For The Birds’ gentlest sounding moments, even when it grows to a slight roar near its conclusion, before stumbling to it that final line. And even within that very apparent toxicity, the drama that unfolds at a deliberate pacing is always compelling.

That slow simmering tension and fragile masculinity in the wake of a break up is then contrasted against yet another dangerous kind of affection on one of the album’s most explosive and soaring tracks—“Headlong.” And if “Lay Me Down” was a mostly straightforward love song with a macabre sense of humor, “Headlong” is simply straightforward with its fondness.

Musically, “Headlong” is the first moment on For The Birds that shows the heights The Frames are able to take things to, and then what happens once they arrive there. Here, the caterwauling that sounds like it is almost on the verge of collapse as Hansard strains for his voice to be heard over the cacophony almost comes as a surprise—there isn’t really much of a sense that the band is really building toward something until just slightly before the song detonates in the face of listener.

Lyrically, 17 years after I first heard it, this is a tough one, because with one ear, I am still listening nostalgically to For The Birds, so a song like this, full of the sentiments that it is comprised of—“Tell me if you’re sure,” Hansard pleads in the moment leading up to the refrain, “And the precious, precious waiting I’ve endured—‘cause you’re all I’ll ever want”—takes me back to a hot, humid Midwestern summer spent living on campus between my junior and senior year in college, and the moments where, I, at the time, believed myself to be, much like Hansard, “falling headlong” for someone.

The way the band is able to control the eventual and gradual release of tension until it becomes too much is still an absolute marvel, and admirable to hear today, but the borderline obsessive, desperate feelings within the lyrics—still applicable of course for listeners in 2021, but the cloying nature of how they are written hasn’t aged well.

You can appreciate it for what was, what it is now, and what it meant if there is no longer space made for it.

*

There was a period of time in the mid-2000s where I was really interested in finding out what books my favorite musicians were reading. At the time, as their profile was slowly beginning to rise, Matt Berninger of The National would famously name drop books he was reading during interviews, as well as slyly working references to the books into National songs.

During a hot, humid Midwestern summer in 2008—the year I turned 25, I bought a copy of the book Ask The Dust from a Half Price Books. Written by John Fante, and published in 1939, the only reason I had even heard of the book (apparently Fante’s most well known work) was because of the numerous references to it1 throughout For The Birds.

From what I recall, it was not a great book, and its protagonist, Arturo Bandini, is an unlikeable character (modeled after Fante himself.)

“There is no answer in the dust,” Hansard waxes on “What Happens When The Heart Just Stops.” Coupling it with the near rhyme of, “And I’m missin’ you so much.”

“Will you come with me and we’ll ask the dust,” he asks on the very slow moving “Giving Me Wings.” And the song itself is not so much a literal interpretation of the novel, but rather a very pensive reflection on something that is over, and beyond repair. Even with its direct nods to Fante’s novel, the lyrics are Hansard at his most poetic and thoughtful, moving away from the dangerous affection and toxicity of the album’s first half, but musically, it is the first moment on the record that really drags the pacing down, perhaps intentionally, as here in For The Birds’ second half, perhaps mirroring the give and take of the way the album opened, The Frames quickly, and surprisingly, contrast this tone with “Early Bird.”

While some songs across the album find a way to precariously balance the sense of tension and release, a song like “Early Bird” is, from nearly the moment it opens after a whisper quiet intro, is all release, unrelenting and bombastic until the very end. And there is an exhilaration to the way band continue to dizzyingly stir blasts of squalling feedback—it can be a little much though now, in 2021; lyrically, Hansard directs the song to a place of heavy metaphor that can be difficult to unpack—in part, there is that feeling of wanting more: “I feel my wheels are turning,” he exhales in one of the song’s quieter moments. “I see the open road before us stretch, leading us somewhere past the hour.”

There is also that familiar toxicity; this time, accusatory and volatile—“Where did this come from?,” he snarls at an unknown antagonist as the song reaches a peak. “How long has this been going on?”

Because of the raw, in the moment, and “in the room” kind of production and mixing on For The Birds, it isn’t weighed down by a lot of, if any, slick effects or studio trickery; however, the very abrupt ending of “Early Bird” is the one song on the record that is the exception. I can only really think of one other song, off hand, that does something similar, and that is the intro to “I Have Patience” by cult-favorite singer/songwriter Mark Mulcahy, but “Early Bird” concludes with the track coming to a halt, and the sound of the tape in the recording studio being rewound. The suddenness of it adds to the overall jarring and surprising nature of the song, and reversed rushing sound proves to probably be as good of any way to lead into “Friends and Foe,” a song that pulls back the noise, dissonance, and explosiveness—retreating and returning to a place of brooding quiet and introspection.

For The Birds is full of moments that soar, but the skeletal arranging of “Friends and Foe” is the first time something swoons, and it’s one of few songs that gives the band’s violinist, Colm Mac Con Iomaire, a spotlight of sorts, as his dramatic, sweeping bowing almost forms a duet with Hansard’s rhythm guitar.

Lyrically, Hansard is not writing from as poetic of a place as he was on “Giving Me Wings.” There is a poetry to them, though, with the way he lets them tumble out, and they do not come from a place of bitterness, per se, but there is a strong feeling of resentment with the way he opts to reflect. “The arms that once held you have receded over time,” he observes in the opening lines; then, making it as clear as he can in the refrain. “And the little love I have for all my friends and foe—and the little lines we’ve drawn between us have taken hold.”

Though, in the final refrain, his sentiment shifts slightly—“And the little time we got to share was worth it, after all.”

*

Initially, I was going to surmise that For The Birds concludes with both an epilogue and an afterword, but I am uncertain if that is accurate.

Of all the songs on For The Birds, “Disappointed” is the most insular sounding—because of the strange, muffling technique worked into the way it’s mixed, which I feel makes it less successful than it could be, but also because it is simply just Hansard, alone, singing with his guitar.

It is one of the songs where he returns to that feeling of wanting something larger, but also is uncertain what that “something” might be. “The years, they get in top of you,” he muses in the song’s second verse. “And I’m just ambling on in this town. I can’t get out, and it drags me down. And these worse don’t really fit what I’m feeling.”

And it is one of the few moments where Hansard seems to have a less toxic moment of clarity in for the way he is surveying the end of his relationship. “How can I be mad at you?,” he asks. “You did what you did and you followed through. You were the one who always said, ‘Forget and move on.’’ He reiterates that he isn’t mad in the song’s refrain, but what he follows that up with isn’t intended to make anyone feel good—“I’m just disappointed.”

“Disappointed” is quiet, like an epilogue—something whispered after a raucous conclusion; and “Mighty Sword” is one last swaying, swaggering breath before the end—an afterward that seems like it is going to shift the perspective of Hansard’s loose, heartbroken narrative—“I may not know you as long as heaven permits. There will be distance,” he admits in the first verse. “And we’ll both have come to expect the wild ending of our dark and feathered friends.”

However, as there song slowly swings itself into the second verse, Hansard places himself in the role of being unwilling to realize that things are over: “You called me over and I’ll wait by your building tonight. But you may not bother, but it’s better than feeding the lie I am receiving. The message that I need to go. But I’m not leaving ’til one of us surrenders its soul.”

“Mighty Sword” isn’t a bad song, or even a bad closing track, but both it and “Disappointed” are diminished slightly, or seem overshadowed by the time they arrive because of the real climax—and arguably the real ending to For The Birds, which is the sprawling, disorienting, combustable, and truly cathartic “Santa Maria.”

There were a number of years where, when listening to “Santa Maria,” I wondered what, exactly, was happening with the rhythm guitar as the song continues to build and build. As a non-musician, I didn’t know there was such an easy explanation for it for the way the guitar sounds—not the tone itself, but the choppy way the guitar is delivered, I guess, for lack of a better description, creating a rhythm that is mostly steady, but often feels like it might be slightly off as the lightly brushed percussion and rumbling bass shuffle in behind it.

Outside of their opening slot for Damien Rice in 2004, I saw The Frames as a headliner almost exactly three years later, at an unfortunately poorly attended weekday night show in Minneapolis at First Avenue. Going on at 10:30 p.m., the group ended their somewhat disoriented set with “Santa Maria,” and I got my answer as to how Hansard creates that specific sound—he’s just slapping the strings with his palm. Partially muting it, but also letting it ring out.

If, on “Headlong,” the explosive ending to the song is a bit of a surprise, the fact that The Frames are working toward something big on “Santa Maria” should not come as a shock at all, based on how much time they spend building up the tension—the sound of the drum stick hitting the hi-hat becoming louder and louder, and the precision with which Hansard slaps the guitar strings to create that cutting pattern becoming more frenetic and looser. There is almost a sinister nature to it all as it simmers for nearly two full minutes before boiling over completely as the band sets the song on fire—dragging it down into another two minutes of chaos and walls of feedback.

It’s the sound of everything actually collapsing around you, but in that dissonance and noise, there is also beauty.

Maybe the most surprising thing about “Santa Maria” is the borderline deadpan, or void of emotion delivery that Hansard uses. From up until this point on the album, listeners should be well aware the power and range he is capable of, but even while the instrumentation is descending into a spiral of tumult, he remains uncharacteristically calm, allowing his voice to just be swept away in the swirling.

And in that calm demeanor he uses, Hansard makes the starkness of the song’s lyrics and heavy-handed metaphor seem even more ominous.

One of the meanings behind the depiction of desolation and heartbreak in “Santa Maria” that I was not aware of until recently is the death of influential Austrian expressionist painter Egon Schiele—his wife, six months pregnant, died from the Spanish flu in 1918.

He died three days later, and so yes, there is a very literal interpretation to the haunting lines in the song’s third verse—“The fever now consumes us both—in the fire now we will go.”

“Santa Maria,” though, is also about a ship. Or, specifically, a shipwreck where there was only one survivor—the Santa Maria De La Rosa, striking rocks off the coast of Kerry in 1588.

Serving as a metaphor for the difficult end to a relationship is not a stretch, or flimsy, exactly, but it is a lot, in terms of its weight, and it’s a kind of overly forceful idea that could buckle if tried by a less capable band, and the effortless, seamless way that Hansard blends both ideas into one stark, solemn tale is commendable—“Let me off of this boat,” he begins in a near whisper. “I’m sick of this ride. The world is heading ever southward and I can’t stay in here.” He then converges the two meanings before splitting them back out again. “And you’re lying awake, away on your side. The feeling comes in waves and burns us, and I don’t want to die.”

For The Birds, maybe due to its nature in leaning towards embittered heartbreak, is an album that feels, yes—it feels quite a bit, but it doesn’t ask a lot of larger questions, and therefore, is not in a position where it would need to answer them. “Santa Maria” is one of the few moments where there are questions with little resolve.

“Santa Maria—why did you have to go?,” Hansard asks midway through. And just before the song beings its slow, deliberate ascent towards madness, he asks one more question: “Why did you have to burn?”

There are no real answers, though, offered. Just responses that complete the rhyme.

*

There’s something still exhilarating about revisiting For The Birds now—it’s an album that I listen to somewhat infrequently, but still know so well. And there’s something about the idea of The Frames that takes me back to that night in Madison, watching them tear through their opening set—wild and unpredictable—the night that made me a believer. And friends, to the extent that I can be, I still am.

I describe the band as being inactive since 2007, save for their one-off, commemorative shows, mostly in their homeland, and the one new song they contributed to their 2015 anthology release.

Describing why there band has been inactive for 14 years is challenging.

I would say it begins with the film Once, but it begins a few months before the film was theatrically released in the United States.

Hansard, together longtime friend, Markéta Irglová, a pianist and singer from the Czech Republic, put out an intimate, somber record in 2006—The Swell Season. Both Hansard and Irglová were then cast as the leads in the musical Once, written and directed by a former member of The Frames—with songs from The Swell Season included within the context of the film. Most famously, the devastating ballad “Falling Slowly,” which won Hansard and Irglová an Academy Award at the beginning of 2008.

A large scale Swell Season tour ensued, and it was, apparently, during this time that the two became romantically involved—their relationship lasting until 2011, when Hansard released the first record under his own name.

Following the sudden, whirlwind success of “Falling Slowly,” The Frames were not exactly less of a priority for Hansard, but he, perhaps in retrospect erroneously, tried to combine both bands he fronted with mixed results. In the fall of 2009, he and Irglová released another album under The Swell Season name—Strict Joy, but in comparison to the simple accompaniment from their self titled effort, the songs included an expanded sonic palette thanks to the other four members of The Frames.

Various members of The Frames have contributed to Hansard’s solo canon, or have performed with him live in the decade that has passed since he launched a career under his own name. And The Frames could always return with a collection of new songs—beloved acts have inactive for much longer than 14 years.

The sudden, puzzling, and messy “end” of The Frames doesn’t damage the legacy of an album like For The Birds, because it captures a very vivid moment for the group. Anecdotally speaking, I would refer to them as a “cult act,” specifically in the United States, where it appeared, at least to me, that they were almost always chasing a larger or wider following, or attracting bigger audiences and more listeners, and were on the cusp of reaching it, but as “The Frames” it remained elusive.

And here’s the thing—you can choose to lose faith in a band after they’ve called it a day, whether there was an official break up, or just becoming “inactive,” or you can continue returning to those moments that made you one of the faithful, allowing those moments to provide you a reminder of why you were a believer in the first place.

For The Birds captures the moment of the band making the album that they wanted to, but had not been able to up until that point—of going for something much larger than themselves. And it’s returning to this album, whether infrequently or not, that keeps me, to the extent I am able to, believing now.

*

If For The Birds ends with both an epilogue and an afterword, then it begins very quietly, deliberately, and beautifully with a slow motion prologue.

Even after 17 years, it’s difficult for me to try and articulate the sensations that stir because of “In The Deep Shade,” and what makes it such a breathtaking, gorgeous, and wholly unique piece—not just as the opening track to the album, but in the band’s entire canon.

Because there, obviously, is nothing else like it on For The Birds, and there is nothing else like it—not even an attempt at another gentle, instrumental piece—on any other Frames record. And there is a part of me, a very small one, that wants to say that it almost seems out of place on the album just because it sets itself so far apart from the other 10 songs that follow—and even though it does appear, at first, to be a strange choice, it also makes complete sense—complete sense in the way that it’s an album full of possibilities; an album full of give and take, tension and release. It’s an album full of sharp contrasts and contradictions, so, with all of the cacophony, catharsis, and bombast that will eventually come—why not begin with something that almost doesn’t rise above a whisper?

I know very little about the mythology2, if there even is anything to mythologize, about “In The Deep Shade.” In the album’s liner notes, it is the only song that isn’t credited to “Glen Hansard/The Frames” for its lyrics, and music, respectively; instead, it’s attributed to Hansard, pianist Rachel Grimes, and the band’s guitarist at the time, David Odlum.

Grimes, an American, was a member of the “chamber music” group, aptly named Rachel’s, which disbanded following the death of founding member Jason Noble in 2012. I was about to say that I am uncertain how an American pianist wound up contributing to a song performed by a very Irish band, but there might be an answer, or at least part of an answer in the simple fact that in 1996, the group Rachel’s released their second album—Music for Egon Schiele.

I am often guilty of wanting too much of a good thing—I want books to continue long beyond their final page, or episodes of my favorite television program to run longer than the 28 minutes they are allotted. “In The Deep Shade” is another one of those things—at three and a half minutes, it is the kind of hypnotic, gorgeous, delicate swirling that I just become absolutely lost in, and could listen to all day.

What makes the song such an experience, though, is the way it deliberately unfolds—there’s a slow, rushing warmth to it all, with the quiet, repetitive flicking sound that you first hear, and the way that the understated guitar works itself into the mix, almost unable to be heard unless you are listening closely. But it is, of course, specifically the dramatic interplay between Grimes’ thoughtful piano playing, and the sweeping strings from Mac Con Iomaire that really make this more of a moment rather than just a song or even a “composition.” It’s the kind of piece that is not overly demanding, simply because it is so quiet and reserved—with Grimes and Cam Con Iomaire knowing how much restraint to practice on their respective instruments—but in its hushed nature, and arresting beauty, it does become something that deserves and demands attention.

It’s transformative—a piece that puts all the little details in the world around you into focus, and breathes life into you when you let it in.

*

On the April night in 2004, after Damien Rice finished his sprawling, disorienting encore, which at times seemed like it was going to go on longer than the actual proper “set” did, as I was being ushered out with the slow mass of bodies ambling their way out of the Barrymore Theatre, I quickly stopped at the merchandise tables to grab something from The Frames—I asked the woman behind the counter which one I should get, and she suggested their recently released live retrospective, Set List, which at the time, served as a sort of “best of” for the band. I am uncertain if there were any other CDs for sale, and if I would have chosen different had I been given a little more time, not wanting to keep the people I was with waiting any longer, and not wanting to hold up the crowd that was trying to make their way to the door.

I recently started wondering if For The Birds was for sale on the table as well, and if it was, should I have bought that instead? Would I have known?

I say that I first truly heard For The Birds later in the summer of 2004—mid to late July, probably, because for a while there, before I actually had a copy of the CD in hand, I had been listening to a very poor quality bootleg I managed to make for myself using my access to the college audio/visual office. My student work job for the summer was in the A/V department and my boss’ computer was wired in and out of myriad recording and playback devices, and at this time, you could stream a very low bitrate version of For The Birds off of The Frames’ website, and through some convoluted, somewhat time consuming methods, I recorded and burned onto a CD-R to tide me over.

I think about how for, like, a month of two, I was fine with a tinny, partially warbled version of the album playing on my discman, and what an eye opening experience it was the first time I actually heard the album the way it was intended—hearing it in my sweltering dorm room during a hot, humid Midwestern summer.

I still think about the summer of 2004, and even when the summer slowly faded into autumn.

I think about what I eventually learned when I was much, much older—something I wish I would have understood at the time, and was too young to comprehend, but what I eventually learned is that there is a huge difference between being “in love” with someone and actually “loving” someone—for the person that they are, not who you think they are, or want them to be.

I still think about the summer of 2004, and even when the summer slowly faded into autumn, then autumn’s descent into a long winter.

I think about that time, and how I was trying to get as tight of a grip as I could and hold onto something that I knew was fleeting.

Friends, I hesitate to say that I left For The Birds behind with a specific time period of my life, but it is closely woven into the fabric of memories and experiences from the time that I still think about, but am also very far removed from. This is an album, and a band, that I “used to” listen to a lot more than I do now—that is, in part, because of how inactive they have been, but also because, thematically speaking, the lyrics of Glen Hansard and his toxic, fragile masculinity have not aged well, and are not the kind of thing that resonates with me, now, staring down the barrel of 40.

Musically, though, as a whole, For The Birds is still a marvel, and listening now, it is still as impressive as it was when I was 21 and heard it for the first time, and I say without hesitation that it is among the ranks of albums that taught me how to listen to music—like how to really listen, and informed how I endlessly try to find the minuscule details within an album’s production.

I think there was a time when I tried to, maybe even subconsciously, take For The Birds and The Frames with me—but what I realized is that this music hasn’t exactly grown with me, and aside from the few thrills it still can provide, two decades later, it isn’t creating new ways to be impactful in my life now. But that is okay.

You can appreciate it for what it was, what it is now, and what it meant if you no longer have space made for it.

For The Birds represents a moment—both for The Frames, obviously, but also for me.

For me, it is a collection of songs that served as the score to what is a time that both surprisingly and unsurprisingly had an enormous impact on my life, and shifted the course my life was on at that time. They were songs that I didn’t look to for inspiration, or even guidance, but I found a sense of solace in them as the seasons continued to change.

For the band, it helped them on the slow journey to larger, international audiences (the opening stint with Damien Rice, also, certainly helped), but it also is a band finding the confidence within to make an album like this, on their own terms—finding the confidence to make this kind of a sound.

The sound of all of us figuring things out.

1- So this is just a quick anecdote that there was no way to fit into this piece, and also this piece is a lot longer than I thought it would be so hey apologies to anyone who was reading it and thought, “Damn, you could really use an editor,” and congrats if you made it this far to the fucking footnotes. In 2007, I put the German film Fitzcarraldo on our Netflix cue, specifically because The Frames wrote a song about it, using the conceit of the film as a metaphor—it’s also the title of their second album, originally released in 1995. The film is about a man who wants to bring opera to the natives in a jungle, and he tries to bring it to them by a large boat, which, at the climax of the film, he has to pull up a mountain. It’s not a good movie, and it is incredibly long and kind of boring, and for a number of years, my wife was very unforgiving of the fact hat I had wanted watch this and subjected her to it.

2 - For a number of years when I was really into The Frames, I tried to get a lot of my friends into them as well. In college it was easy—less so when you’re older and meeting people is challenging. I’ve more or less fallen out of touch with my friend Chris; he lives in North Carolina now and I actually had no idea he had moved there, which proves how good the both of us are at staying in touch. But I had introduced him to The Frames and we had gone to the very poorly attended show at First Avenue together in 2007. He told me a story once about “In The Deep Shade” that I don’t remember all that well but I think it involved Rachel Grimes being hesitant to play on the song because she needed to travel in order to record her part, and didn’t want to because of an ill family member who may have passed away while she was recording the song? I am uncertain where one learns about a story like this, because in my internetting about this album, I did not encounter this story.