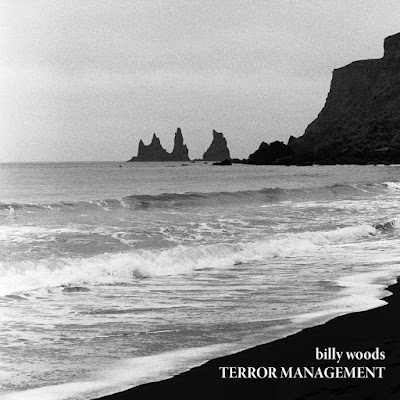

Album Review: Billy Woods - Terror Management

The outlook found on nearly every album from Billy Woods

could accurately be described as ‘incredibly bleak.’

Even before he released the jaw dropping, visceral, and stark Hiding Places earlier this year,

produced entirely by Kenny Segal, and even before last year’s dizzying,

cacophonic, and dark Paraffin—the third full length from Armand Hammer, Woods’ project with rapper and producer

Elucid—there has always been a long, ominous shadow looming over his output.

Terror Management,

a blistering, unnerving new collection of 18 tracks, is no different.

*

My wife recently joked that she and I are ‘the 1%’ simply

because we pay to have three different streaming services—Netflix, Hulu, and Showtime.

The latter is my choice, simply because I want to watch “Desus & Mero” and

am willing to spend $11 a month or whatever on it.

“Desus & Mero” returned recently from an extended

hiatus, and one of their first guests since coming back this fall was writer

Ta-Nehisi Coates, out on the promotional trail of his just released novel The Water Dancer.

During his interview on the show, Coates discussed how

hip-hop—specifically very lyrically heavy hip-hop—has influenced his work.

“These are some of the

greatest writers that we’ve got—period,” he exclaims, emphatically, before

citing both Black Thought from The Roots and Nasir Jones as examples.

And that’s the thing, isn’t it? The worlds of music and

literature are so compartmentalized that rarely, if ever, do people look at

songwriters the same way they look at a novelist, or an essayist. And even if

the zeitgeist lauds a songwriter for the way they work with words—it’s people

like Bob Dylan, or Joni Mitchell. And that’s the thing, isn’t it? That culture,

as a whole, is so dismissive of the thoughtful and clever power that is deeply

embedded into hip-hop.

Before anything else—before calling him a rapper, or a

producer, I would call Billy Woods a writer, and one hell of a storyteller.

Because that’s what he does—within the unrelenting, at times frenetic and

desperate delivery of his rhymes, are stories; stories that blur the line

between fact and fiction; and most importantly, stories that take you from

wherever you are while you are listening to his music, and they place you

within the images created by those words.

Very few rap artists working today have the gift that Woods

has, and that’s the ability to conjure and evoke—and while musically, Terror Management lacks the overall

cohesion in sound that Hiding Places had

because it was a co-billed collaboration with one, and only one, producer,

Woods’ uncanny, effortless ability to turn a phrase and take you with him into

those moments more than makes up for the at times scattered, and disjointed

production that runs throughout.

*

I stop short of saying that Terror Management, much like a lot of other, very recent rap

releases, falls into the category of ‘sound collage,’ but structurally, it has

little in common with what you may think of when you think of a traditional rap

record—across the album’s sprawling 18 tracks (though relatively short running

time of 42 minutes), the longest song included is just under four minutes; the

shortest is just over a minute; and it’s built, much like previous Woods record

(Today, I Wrote Nothing comes to

mind) around incredibly tight, concise bursts that never feel unfinished by the

time they reach a conclusion, as well as myriad, disembodied samples of dialog,

usually placed near the end of a song.

After short intro from an a piece of dialog spoken by Kurt

Vonnegut, there’s an awful sense of foreboding that descends onto the album, as

Woods repeats the unsettling expression, “World getting warmer—we’re going the

other way,” on the album’s opening track, “Marlow.” And it’s within the first

song that you get a sense for just how intelligent and how literate of a writer

Woods is. On Hiding Places, among

other things, he references Great

Expectations and Glengarry Glen Ross;

on “Marlow,” he spends the final lines of the song talking about Kafka’s “The

Metamorphosis.”

After short intro from an a piece of dialog spoken by Kurt

Vonnegut, there’s an awful sense of foreboding that descends onto the album, as

Woods repeats the unsettling expression, “World getting warmer—we’re going the

other way,” on the album’s opening track, “Marlow.” And it’s within the first

song that you get a sense for just how intelligent and how literate of a writer

Woods is. On Hiding Places, among

other things, he references Great

Expectations and Glengarry Glen Ross;

on “Marlow,” he spends the final lines of the song talking about Kafka’s “The

Metamorphosis.”

Literary flexes like this, sure, are impressive to drop into

your lyrics, but as the kind of listener who always wants to know more, by

doing this Woods, perhaps inadvertently, encourages you to investigate

references or source material you may not be familiar with—the title of his

album Today, I Wrote Nothing comes

from a collection of writing of the same name from Russian writer Daniil

Kharms; here, on Terror Management,

Woods references poet Jack Gillbert on

more than one occasion.

Similarly to the tone Woods helps set on Paraffin, there is a very noticeable

sense of immediacy and urgency running throughout Terror Management—it’s in the way he, very deliberately, delivers

his lyrics; it’s in the way he emphasizes specific words or lines, and it’s in

the way that he is able to convey a breathless, unrelenting feeling of

borderline desperation at times—these thoughts and these words need to get out there, and no one, save

for Woods himself, understands just how serious it is that he does this.

“Catch-22,

Catch-22—when I laugh, miss you worse,” he barks over the on the beginning

of “Great Fires.” Then, later on in the song’s second verse, “It was fine till everybody left—but it was

terrible for they did, like holding your breath…I remember how she waited for

me to say it; breath bated, we was on the phone—I wish I could have waited

inside that moment forever.” And this is just one example out of an almost

innumerable amount where Woods is able to do more than just make you hear these

lyrics—he pulls you into this scene with him.

It’s also on “Great Fires” where Woods creates a near mantra

with the song’s refrain—“Even good news

feel bad. I drink drinks too fast; I paid cash.”

Before this, on “Gas Leak,” he creates one of the bleakest

images on the record—“No Christmas this

Christmas—kitchen frigid, space heater in the room, Chinese delivered,” all

before conjuring terribly evocative, marginally ambiguous, and emotional

imagery: “I am an isthmus; my arm's length

is quite the distance; once distant future now day-to-day existence; my ex wife

is my mistress,” an idea that shows up more than once on Terror Management, and is mentioned at

least once on Hiding Places.

Musically, Terror

Management from beginning to end is kaleidoscopic, dizzying, and restless.

Because Woods has worked with a number of producers on the record, it never

settles—or really, refuses to settle, into a specific, cohesive sound; at

times, it can be the record’s fatal flaw, creating a disjointed, loose

environment—other times, it lends itself well to the overall sense of

unresolvable, unnerving tension stretched across every single one of these

tracks.

There are beats that are slightly more successful in their

execution compared to others, and when one of them works, it really works—the smoothed out groove of

“Western Education is Forbidden” provides a surprising juxtaposition against

Woods’ stark lyrical portraits; the unsettling stutter and slink of “Blood

Thinner” lays the ground for a haunted atmosphere where Woods, not as a

lyricist but as a performer, thrives with his animated delivery; and the

chaotic, abrasive dissonance in the double shot of “Dead Birds” and “Gas Leak”

creates a cacophonic peak as Terror

Management hits the halfway mark.

Woods’ lyrics, and his confidence and intelligence as a

rapper are without a doubt what makes the album work, even when it gets weigh

down aesthetically; however, it’s also the usage of dusty, at times mysterious

snippets of dialog that find their way into the conclusion of a number of

tracks—the one that stands out the most, perhaps because it is a dialog between

two people, is the sample included at the end of “Birdsong.”

Or, perhaps it stands out because it takes up nearly half of

the song’s three minute running time; it’s a fascinating, intense back and

forth between a man and a woman, presumably husband and wife, about the idea of

dreams, and authenticity.

“You got to fake it. Because we don't have dreams these

days. How the hell can you have a dream, for what? So, so everybody's jiving.

Well let's jive on that level,” the

woman tells this man.

“If I love you, I

can’t lie to you,” the man retorts.

The conversation ends with an exchange about the man’s

temperament with his white boss at work—and how his temperament shifts once he

returns home.

“I've caught the frowns and the anger. He's happy with

you. Of course he doesn't know you're unhappy. You grin at him all day long.

You come home and I catch hell, because I love you. I get least of you. I get,

I get the very minimum. And I'm sayin', you know, fake it with me,” she asks him in the end, before the song

ends with the repetition of one line—“Just the age for heartbreak.”

The inclusion of

these samples, usually found at the end of one song as it careens into the

next, seems to be in effort to compliment, or amplify, something from the song

itself—a specific image or an idea. In the case of the shadowy, and more than

likely very personal “Corn Starch,” the decision to end the song with a bit of

condescending dialog taken the 1974 Francis Ford Coppola film The

Conversation, provides a connection to an almost seemingly throw away line

that arrived shortly before the song ends—“Down the road, seen him lookin'

bummy outside the liquor store—Hurried past like I ain’t know him, somethin'

caught in my throat.”

*

Much like its predecessor, Hiding Places, released only, like, seven or eight months ago, Terror Management is a difficult

listen—though with enough time, it reveals itself to be a rewarding and complex

one as well. And much like its predecessor, it leaves the listener with no easy

answers, and possibly with more questions. Rap music doesn’t need to be, or have

to be challenging, but as a genre, it becomes more interesting when the performer

wants to be difficult or challenging—and pushes the boundaries of the genre to

dark, confrontational, realistic, and at times, very depressing places.

Terror Management

ends with “Stranger in The Village,” an unrelenting two minutes, musically

steeped in minor psychedelia, where Woods, at the beginning of the song,

announces that it’s his ‘European Vacation,’ before rattling off a sprawling

verse that references an obscure, unpublished book called Barracoon: The Story of The Last ‘Black Cargo,’ and ends the track

by saying, “Everything for sale except

the scale—that’s coming with me,” and possibly one of the darkest phrases

on the entire record, “You can’t pay with

money—I know what’s coming.”

The outlook found on nearly every album from Billy Woods

could accurately be described as ‘incredibly bleak,’ and while Terror Management ends in a less

unsettling way when compared to the final, visceral moments of “Red Dust,” the

breathless closing track on Hiding Places,

it still leaves the listener with holding onto something very heavy to unpack,

standing in a dark place, with little, if any, light to find a way out.

And Billy Woods, as a performer, and a writer, wouldn’t have

it any other way.