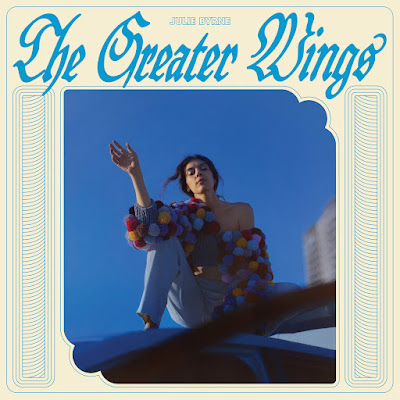

Album Review: Julie Byrne - The Greater Wings

And they are now, perhaps, not quite as idiosyncratic as they were a decade or so ago as a format, but cassettes, even within the incredibly minor and certainly novel resurgence they’ve had over the last few years, will remain firmly in a small niche—regardless of however many marquee name artists, like Lana Del Rey, or Taylor Swift, opt to release their most recent albums, for whatever reason, alongside CDs and vinyl, on cassette.

I am certain I have, at least in passing, written about “tape labels” several times in the past, or more than likely, elaborated to some extent on how I found myself wading further and further out into what was, to me, at the time, the somewhat surprising amount of tape labels that were active in, like 2011 and 2012, as well as the very idea of what I could only refer to as the cassette culture of this era.

It did begin innocuously enough with a one-off purchase, within the earliest months of 2012, from Bridgetown Records—based out of Southern California, the label itself had a run of roughly a decade, releasing the occasional 7” single, 12” LP, or a handful of CD-Rs—but a majority of the 100+ titles issued under Bridgetown imprint were put out on limited edition cassettes.

And this was at a time when I had an office job—and to fill my workday, and often in an effort to fill the quiet that surrounded the desk that I found myself at, I would spend parts of my afternoon combing through different genre tags, and sampling different artists on Bandcamp—one of the genres that I spent the most time exploring was “shoegaze,” and while I don’t think I would ever refer to her output with that description, browsing that tag did eventually direct me towards the self-titled album, originally from 2010, and its follow up, Sleeplessness, issued in 2011, from Charlotte Oleena, who released music under the name Sea Oleena.

Both albums had been collected onto one cassette, which had been somewhat recently released on Bridgetown Records.

Part of the charm, I would find, at least at first, with ordering from small cassette labels, like Bridgetown, was the personal touch the person running the label—it was always just one person—would take with what they put together to send off to you. Sometimes it was just the placement of odd or whimsical stickers on the outside of the bubble mailer itself—other times, it was a simple note of thanks, or a strange doodle on a scrap of paper, tucked into the package.

The head of Bridgetown, Kevin Greenspon, was, at this point anyway, someone who hustled extraordinarily hard for the label he was running—within the small envelope that Charlotte’s cassette had arrived in was a handwritten note that, yes, thanked me for the order, but Greenspon then, within the message, recommended I take a listen to another Bridgetown release—Ashes, from the haunting, spectral folk outfit, Reighnbeau.

Take a listen, yes, but the implications were, of course, that I would place another order from Bridgetown for additional titles.

Which I what I certainly did.

It started innocuously enough with a one-off purchase near the beginning of 2012, but within a few months, through artists issuing material on Bridgetown, and through Greenspon himself as a resource or connection, I began discovering just how many cassette labels were in operation, and then learning what I was able to about the very idea of cassette culture.

The labels themselves were always run by literally just one person, and honestly, it was usually, and maybe still is, a man in his 20s, and what was surprising to me, while I was being introduced to this new world of extremely underground music and of D.I.Y. ethos, was just how much overlap there was from label to label—someone who ran one cassette imprint would often play in a band that would release music as part of a split cassette (meaning two artists sharing one cassette, each taking a single side) issued through an entirely different label.

It was through Bridgetown Records, and this wading out into different labels, that shortly after its release through the imprint Solid Melts, I came across the debut EP from Julie Byrne—You Would Love It Here, It’s The Perfect Place For You.

There were a number of things that drew me to You Would Love It Here—the title, for starters, was, and still is, incredible, and it could be read as both sincere or cutting and sardonic. There was the cassette’s artwork, then, too—a yellow drawing of a strange figure riding atop an even stranger creature, Byrne’s name nowhere to be found on the cover itself, and its title stacked up in ornate dark blue lettering underneath the drawing.

There were a number of things that drew me to You Would Love It Here—the music was, and still is, alluring and compelling. Byrne was barely in her 20s when she recorded the material for the cassette—her voice, though, even when she was a much younger performer, had that otherworldly, haunting, and hazy quality to it.

Not nearly as smoky, or confident, as it has become over the last decade and within the songs from You Would Love It Here (and another EP released on cassette in 2012) retrospectively, both of these short collections can be seen, or heard, rather, as the sound of a new artist that was beginning to find her way—room for plenty of growth, or development, but Byrne arrived armed with a smoldering, haunting voice and a gentle way with the guitar, and an impressive amount of potential through both her way with words, but also a kind of spectral stoicism that you could feel deep within while listening.

*

For at least the last two years, and perhaps even longer than that, I have been, at the very least, acutely aware of my interest in the idea of a convergence—specifically, what happens when two things that are not drastically different, but different enough, begin to slowly collide into one another, with my fascination then being on whatever forms in that space between them.

This concept has been something I have used as a frame within music writing—a flimsy device that I have certainly overextended—as a means of unpacking an artist’s or group’s sound, or overall aesthetic, if they are perhaps influenced, or inspired, by two different genres or even contrasting extremes, then the focus being on those differences, sure, but what I find to be much more compelling is whatever will occur when the distance between those two things becomes smaller, and what is ultimately created within that convergence.

At some point toward the end of 2019—in late autumn, maybe, I had a conversation with a friend that we never really finished.

There never seemed like an ideal time to bring it back up, and certainly, too much time has elapsed now to try to do so, and there is a part of me that is certain she would not even remember the original exchange, or that she would even be willing to entertain my earnestness on the matter, but she told me she believed that grief and joy could coexist with one another, and that through her beliefs in that, she was trying to find that place, for herself, as a means of coming to terms with a grief she had been, up until that point, attempting to stay a step ahead of.

She isn’t the only person who subscribes to this—this place where there is a belief that these opposing states can coexist, and at the time of this conversation, I stop short of saying that I didn’t believe that it was possible, or that I simply just did not believe her, or her intentions in the conversation, but I had a difficult time understanding.

I think what I said was that I didn’t see how it that possible, and that even if it were possible, I wasn’t certain how I would ever be able to arrive at the place of that belief for myself.

At the time of this conversation that was never really finished, I thought that place—the place where, for me, grief and joy could coexist, or be in some kind of duality within my life, was something I would be perpetually trying to find, or reach.

That wasn’t the case, though, which comes as a surprise to me now. That kind of coexistence isn’t something I spend a lot of time thinking about at all now.

Grief, as a feeling, or a state of being, or as a somewhat tangible thing, is something that I have carried a lot of with me over the last decade, and because of that, grief, as a theme, or a suggestion, would eventually find its way into things that I would write—not always shaping pieces entirely, but shaping them enough, yes, and certainly informing how I was writing in ways that I had, perhaps, not anticipated it would.

It was certainly an idea that I wrote about, at times even at length, in 2022, and maybe there are hints of it in things written during the years immediately before that, but outside of the idea of a convergence, or a collision, of things within the space of contemporary popular music, I find that I spend a lot of time ruminating on—both in writing, and certainly outside of it—platonic love.

There are so many songs about love, or maybe more accurately, the emotional highs and lows that surround the idea of love—there are songs about unrequited love, or about tension and desire, or about the heartbreak and anguish that comes when the love, in question, has come to an end.

There are certainly so many songs about being “in love” with another person, but there are arguably fewer songs about loving that same person for who they are—for better and for worse, rather than the idealized version of them that the protagonist in a love song is chasing, or falling toward.

If there are arguably fewer songs about loving a person for who they are—the love is almost certainly of a romantic nature, because there are even fewer songs that are inherently about platonic love.

There is a possibility that I could be making more work for myself—not in the sense that I am looking for something, within contemporary popular music, that simply isn’t there, but I am looking at it closer, and finessing it enough, or interpreting it a particular way, because I do find that when I am listening to a song that doesn’t have to be a “love song,” but may have a romanticism to its writing, that I am analyzing its lyrics in a way to look, or rather, listen beyond the implications of romance, and to find where there could be, and often is, the hints of a different kind of love to be found.1

And I am thinking about the intersection, or the convergence, of grief and love.

When the distance between the two becomes shorter and shorter, and what forms within the center of this collision.

*

In 2014, Julie Byrne’s two cassette releases were reissued on vinyl under the name Rooms With Walls and Windows, through Owen Ashworth’s Ordinal Records, and the collection, though made up of material that had been previously released (albeit in a very niche and limited form) was viewed as her debut full-length, which did make writing about some elements of her 2017 effort, Not Even Happiness, a challenge, because the record was billed as her sophomore effort; and yes, technically it was, but given that it was a collection of new material, for me anyway, I took it as a proper debut, or at the very least, a reintroduction of sorts.

At the time of its release, part of the lore around Byrne and Not Even Happiness was about her nomadic lifestyle, or just how enigmatic she was being perceived as at the time. In the interim between Rooms With Walls and Not Even Happiness, among other things, Byrne had spent part of 2016 working as a park ranger in New York. Byrne was experiencing the world, as she was able, rather than simply just existing in it, as so many of us do, and there was a restlessness within her spirit at this time that certainly found its way into her songwriting, which you can hear echoing throughout her lyricism on Not Even Happiness—certainly in the song’s sweeping, gorgeous opening track, “Follow My Voice,” where she sings, pointedly, “I’ve been called heartbreaker for doing justice to my own.”

Following the release of Not Even Happiness, Byrne was, in a sense, still living a nomadic, enigmatic life—though, like the title of Not Even Happiness’ final track, “I Live As A Singer Now,” she toured to support the record throughout 2017 and 2018, and eventually relocated to Los Angeles, where she remained until 2020, when she opted to return to Chicago, a city she had once resided in before—now as a means of being nearer to her closest friend, collaborator, at times her roommate, and for a while after they had initially met a number of years prior, her romantic partner, Eric Littmann.

Littmann passed away unexpectedly in June of 2021, just as the duo had both intended on hitting the road together on a tour, and as work on a follow-up to Not Even Happiness inched toward completion. In her shock, and grief, over the loss, the album, still a work in progress, was shelved for upwards of a year before Byrne began revisiting the material.

Completed with the assistance of both Jake Falby and Alex Sommers, the large portion of the album, The Greater Wings, her first full-length in over six years, was apparently already written and at least partially recorded before Littmann’s death. And it is this fact that makes it a record that is, in the kind of mythology surrounding it, and the weight it holds, it is similar to Nick Cave’s Skeleton Tree—a record that was nearly finished at the time of his son’s accidental death, and regardless of when the lyrics were penned, for the listener, the shadow of that loss hangs heavily over every song.

Littmann’s passing, and Byrne’s still incredibly raw grief over the loss, can be found throughout The Greater Wings—a collection of songs that are exponentially more robust in their sound when compared to both Byrne’s humble, sparse beginnings from her cassette EPs, and even the maturation that she had found on Not Even Happiness. It is a dense, complicated record, both in its aesthetic, but also in its lyricism—Byrne, in her reflective, often tender phrase turns, intentionally offers no easy, or “right” answer to the larger questions of how one processes a monumental loss like this, but rather, makes a space for us to sit alongside her within the intersection, or convergence, of grief and love.

*

What I had forgotten, until recently, was that Not Even Happiness was released in January 2017.

The time of year that a record is released might not be that important of a detail for you, as a listener, and there have been times when the season a record has been released within has no real bearing on how I feel about it, or what I associate with it when I revisit it, but a number of the records, or songs, that I have held the closest and carried with me through my life, are connected to a particular month or season.

Not Even Happiness doesn’t feel like a “winter” record, even though it arrived into the world during the bleakness of January—it does, often, feel like a record that could find a home within literally any of the other seasons. It’s a record that sounds like autumn, within the huskiness of Byrne’s voice and the warmth of the acoustic guitar string plucks and strums.

It could be a summer record, too—in its gentleness, and a vague memory I have of listening to it in the car while driving home on a hot summer afternoon.

In turn, I am uncertain if The Greater Wings is a “summer” record, despite its arrival at the beginning of July. The summer, or at least the month of June, carrying weight for Byrne as it is the time of year when Littmann passed, but in its musical structure, and within Byrne’s poignant and often earnest lyricism, it’s a record that both could seem at home during any of the seasons, depending on the song itself, or the tone you wish to strike within your listening, but it is also a record that in its robustness and thoughtfulness transcends any connection to a specific time of year, or month, but rather, attaches itself to your life—your present and future certainly, but through the exploration of grief and love and what occurs at that intersection, it can find a way into the recesses of your past as well.

Byrne is now in her early 30s, and even in the years that she did spend simply traveling, or working as a park ranger for, seemingly, the experience of it all, there has been no shortage of growth in her sound, or the way these songs are arranged. Nobody could have expected, or should have wanted, her to remain working within the sparsity of her earliest material from well over a decade ago, and there was undoubtedly growth to be found, and heard, on Not Even Happiness, but the depth that the songs found on The Greater Wings has is astounding.

As an artist rooted in a more folk-oriented tradition, there is, of course, a lot of acoustic guitar on the record. It is, in fact, the first thing that you hear on the gorgeous, devastating, opening (also the titular) track, but it is not the instrumental focus the way it was for her in the past, as she has incorporated and embraced layers of lush sounding strings, textural synthesizer washes, the harp in a number of places, and the haunting inclusion of the piano, which is used incredibly well on the centerpiece “Lightning Comes Up From The Ground,” and on the breathtaking finale, “Death is The Diamond,” which is one of the song that Byrne penned after slowly finding her way back to working on The Greater Wings after shelving it for a year.

Structurally, like Not Even Happiness before it, The Greater Wings opens up with what is one of its absolutely finest, most stirring moments.

“The Greater Wings,” before it actually starts, opens with silence—or, rather, before Byrne’s fingers begin to glide across the tension of the acoustic guitar strings, there are roughly two seconds of the quiet, organic hush that can be heard throughout the song as it unfolds. A whooshing that is not explained or detailed in the liner notes that Byrne wrote for the album—giving “The Greater Wings” a very “in the moment” kind of feeling; like that sound is the wind, itself, or the sound of traffic coming from an open window, in a world just beyond, or outside of the one that is being created within the song itself.

The seemingly effortless build-up within “The Greater Wings”—the way Byrne hangs on during the rise and then rides out the gentle falling that the song is constructed around, is, outside of her unmistakable voice and the personal, observational writing she taps into right away on the album, what makes it as astonishing, and evocative of an opening track as it is. And within that rise and fall, the string arrangement within the song gives it a truly cinematic quality when the music begins to swell, just for a moment—a song that is less based on the idea of “tension and release” and more around the understanding of when things need to surge, or a slight rush needs to be felt, specifically here in the chorus, before receding and leaving Byrne to carry the verses along with a gentle contemplativeness.

With as intrinsically close as Byrne and Littmann had been, he had, in the past, been the subject, or at least the inspiration, of some of her writing—“Follow My Voice” was both about him and dedicated to him. So, in the songs that were written for The Greater Wings prior to Littmann’s death, I am uncertain how many of them would have been similar in terms of their sentimentality, and in the title track, Byrne has penned a song that is both, like “Follow My Voice,” about him, as well as a touching reflection and dedication to him, and his effect on her life.

“I drank the air to be nearer to you,” Byrne begins quietly at the top of the song, before slowly pulling the song into more evocative vignettes or moments of her life with Littmann, though poetic and fragmented in their description. “Music in the walls,” she continues during the first chorus. “You were in the moment with your life across the chord. Was this always, or never before?”

As “The Greater Wings” continues to swell, and then recede, in the third verse, Byrne perhaps blurs the line a little in her writing in giving a clear nod to Littmann—the blurring, or ambiguity, arriving in what could be a nod to the dynamic their creative partnership had, referencing the intensity and intimacy of their relationship as a whole, or maybe even a little bit of both, as she sings, “I hope never to arrive here with nothing new to show you, as so many others have.”

And it is not so much an in-joke as it is a subtle and very personal acknowledgment in the chorus that Byrne arrives at in the middle of the song, where she writes in more detail about Littmann’s work as a musician outside of their partnership. Littmann was a member of the instrumental collective Phantom Posse, and their last release (issued in 2020) was titled Forever Underground, which Byrne ruminates on briefly—“You’re always in the band, Forever Underground,” she sings delicately before pushing her voice into a higher range to soar alongside the gradual rise in the music around her. “Name my grief to let it sing—to carry you up on the greater wings.”

*

Something that I have come to understand about myself, for better or for worse, within the last few years is that I am surprisingly earnest and sentimental.

The sentimentality, or earnestness, can be a surprise, I think at first, because I think I can, and in the past certainly have, come off as regularly surly, or even caustic in some situations; and the earnestness, and sentimentality, I have found, hasn’t been received poorly exactly but it has also not been received as well as I would have hoped, or intended, or really reciprocated in a way that felt sincere.

Other times, the level of earnestness and sentimentality is matched, or even exceeds, in how it is returned to me.

And I mention this because there is, as you might anticipate given the personal nature and emotional heft of The Greater Wings, a level of earnestness and sentimentality that courses throughout, certainly, but there are specific phrase turns in certain songs that are very unabashed and open—Byrne, even in her earnestness, often weaves those sentimentalities into her poetic ambiguity, so it does become refreshing to hear when states theses kind of emotions plainly.

The Greater Wings’ second track, “Portrait of A Clear Day,” is less ornate in its arranging when compared to how the album opens, and Byrne’s acoustic guitar bounces along slightly—the song as a whole is much more steeped in the kind of folksy, or rootsy sounding material from her past, and like the album's title track, there is a natural, although cavernous sounding reverb, lightly coating both the smolder in Byrne’s voice, as well as her guitar playing, making it sound all so much larger in scope while it echoes off of itself slightly.

“Portrait” is a moment when, at least in its final breaths, Byrne does pull away from the use of these vivid, though intentionally vague, descriptions within her writing—but that doesn’t mean she pulls away completely, as she does use them enough throughout, leading up to the final exhalation.

“Beside you, I drank from the pitcher of life,” she begins. “Whispers as not to wake the land.” And the notion, or theme, of loss was certainly introduced the moment the album began, but it is within “Portrait” where Byrne begins to play with the idea of loss, and pulls it into different places—there is, of course, the grief that she is continuing to work through as best as she can, but here, it is where you can hear her writing from a place of longing. And not even a romantic kind of longing, exactly, or a “desire,” if you will, but rather the missing of a connection, or the need to reconnect with someone you care a great deal for.

You can hear that sense of longing in the final words Byrne sings in “Portrait of A Clear Day,” which is the first time on the album where she does step out from the more poetic nature of her writing, and is very open in her candor. “Your love filled me like summer ground,” she confesses. “Passed me like the rising sign—and I get so nostalgic for you sometimes.”

*

In its structure, I stop short of saying that, sonically at least, The Greater Wings becomes more experimental or, at the very least, more textured, the further you wade out into it, but there is a noticeable loosening of Byrne’s grasp on the folky, more acoustically oriented arranging, and in turn, you can hear her reaching out and beginning to wrap her hands around the low, rippling synthesizer tones—there are moments where she is able to build a space that will hold both of them, like “Flare,” which leans more into the acoustic instrumentation from her past, while a song like “Conversation is A Flow State” is firmly based in a warm, melancholic, electronic atmosphere.

“Flare” arrives after the halfway point of the record, as does “Conversation,” and the former begins with an intentionally slow build-up of a quivering, ethereal sound that grows in volume until Byrne herself, and her acoustic guitar, arrive.

Within “Flare,” Byrne, in her writing, as the gentle finger-plucked strings and synthetic moods swirl around her, as well as the gradual swelling of a string arrangement within the second half, does remain in the place of bittersweet longing and grief, and this is not to say that she, as a character or person, has been extracted from the narratives of the record, but this song, at least, is one of the places on The Greatest Wings where it feels like she’s referencing herself a little bit more.

“Drive with me,” she begins, in her slow-burning, lower register. “Never knew what I wanted, only how to let it go,” she continues. “The curves of the mountains rest in me. I find there are times I’m in touch with who I truly want to be.”

“Flare”’s second verse becomes even more evocative, if not more ambiguous, in the imagery she uses. “Meet me on the dance floor where I move in my own name,” Byrne coos quietly, before sliding into the chorus. “One more hour, gorgeous and wild. I could have done better, you’re not the only one,” she reflects. “I know you, I see your determination—remember our time for years to come.”

Sonically, “Conversation Is A Flow State” is one of the more inherently inward songs on The Greater Wings—again, like “Flare,” it opens slowly, and deliberately, with the building of a pulsating, chillier synthesizer tone that eventually fades away and makes room for the warmth of what is ultimately a melody played on something antiquated and warm in sound—not quite the sound of a Rhodes electric piano, but it gives “Conversation” a soulful, pensive feeling in how it all unfolds underneath Byrne’s musings.

With an album about grief, and loss, and the attempts to not even process it, or find a way “through” it, but just find a way in its wake, of course, the word “haunting” would, and could, be used to describe the project as a whole, but there is a specifically kind of chilling, and haunting nature to “Conversation”—mostly within the vivid imagery that Byrne conjures in the lyricism, oscillating between fragments that depict what appears to be pieces of both her love and relationship (in all forms) with Littmann, and then plunging herself into the confusion and anguish that comes with grief—sometimes all of it within the same breath.

“At dawn, you said that you cared for me without really asking who I am,” she begins as the mournful synthesizer tones tumble out underneath her voice. “You know, there are ways I relate to it—I let so few see me truly.”

The song takes a more shadowy turn within subsequent lyrics: “Did I get blood on the masterpiece?,” she asks pointedly at the start of the second verse. “I got blood on the sheets—it’s alright. Move my limbs toward sonic reach,” she continues; then, in the third verse, finding the space between surrealism, or metaphor, with imagery much more grounded. “Right then, your touch was medic. And maybe that is all it was. But conversation is a flow state,” Byrne explains. “When the energy opens up.”

I would, at no point, really describe much, if any at all, of Byrne’s canonical works as being “lusty,” but there is a surprising kind of lustiness, or sensuality, that comes through in the latter half of “Conversation,” as well as a sense of conflict, or a kind of unrest, between that sensuality, or lust, and the grief that eclipses The Greater Wings.

“I was burning too hot and alive,” Byrne sings, and repeats, and just before that, says, “Missing nights of feeling intricate—I miss getting the moment right”—sentiments that are, then, carried into the final verse, which is the most poignant or telling of the song as it continues to unfold itself slowly. “Permission to feel it—it’s alright,” she says, not really so much asking, but more of a declaration to herself. “Permission to grieve—it is alright. Healing can be heartbreaking—it’s alright,” she continues. “I am by your side.”

“Conversation,” like literally every song on The Greater Wings, moves at a very intentional pace—and since it is constructed around subtle synthesizer tones and shifts, the tempo is not exactly a quick one, but it for as subtle or quiet and reserved as it is, “Conversation” is unrelenting, in the way that Byrne continues to deliver these lyrics in something close to a stream of conscious, before breathlessly arriving at the conclusion, moments before the song comes to an end: “Time moves, there’s not much left to say. I’ll leave it on one thing I know—you’re a less I won’t forget. Your fear is not mine to hold.”

*

In advance of The Greater Wings, Byrne issued three singles—and while neither Byrne, herself, as an artist, nor the album as a whole, are, like “single” oriented, I did both appreciate that Byrne had returned with the rollout of new material after six years, and the chance to hear a little bit of the album before its arrival in full.

The title track was released as the second of the three, which conveyed just how serious and personal The Greater Wings was poised to be; and the final single, coming roughly a month before the release of the record, was the album’s simmering, tense third track, “Moonless.”

There were a handful of interviews, or profiles, on Byrne in the weeks leading up to the release of The Greater Wings, and in one of them, it details her picking up the piano, which is an instrument that has never, up until now, been featured very heavily if at all in her output, and on “Moonless,” both she and Littmann are credited in the liner notes as playing the instrument on the brooding, dramatic, and stunning track.

There are places throughout The Greater Wings where the album’s tone shifts into places that could be described as both eerie and chilling, and that is not the overall feeling that Byrne is often going for with her music, but she really goes for it, and succeeds, on “Moonless,” which in the slow piano progression and the way she plays with the natural tension and release of her voice in how she delivers the lyrics—at times, surprisingly similar or at least arguably reminiscent of the more reserved, somber songs from Grouper’s last two albums, as well as a hint of early Fiona Apple, though perhaps that has to do more with the use of the piano itself, and the timbre of Byrne’s voice.

“Moonless” works through a lot of different emotional states—like “Conversation Is A Flow State,” there is a little bit of a restlessness or lustiness, though not as obvious, and really only in the first few lines, which are among the album’s most evocative just in terms of how vivid of a portrait Byrne can create. “That night at the old hotel, I’d been learning you by heart,” she begins. “Voices rising through the smoke, tables caving in. I found it there in the room with you—whatever eternity is.”

That restlessness, or lustiness, does begin to shift into more of a frustrated desperation, though, in subsequent lyrics on “Moonless,” specifically in the second verse, and in the short, anguish-filled chorus. “What does it matter, the story?,” Byrne poses later on in the song. “If your absence remains, I feel it right here—what eternity becomes.”

“I’m not waiting for your love,” Byrne states in the chorus as the song’s swirling string arrangement begins to spiral around her with a cinematic quality, then repeats it again, creating a moment both stark and fragile that creates a juxtaposition of feelings, or highs and lows, that are found within any kind extraordinary close relationship with another.

*

Death to the old ways—but who am I without them?

Something that I have noticed about The Greater Wings the more time I have spent with it in the weeks since its release, and this is, like, not a fault of the album, but nearly every song opens with a very deliberate introduction—often short, and in a number of occasions, the tone, or composition of the intro has little to do with how the song will sound, or feel, once it actually “begins.”

If anything, it is somewhat refreshing, and as someone both listening for enjoyment (as much as someone can “enjoy” an album that is as emotionally devastating as The Greater Wings can be) as well as for analytical purposes, it is genuinely interesting in terms of structure—something brief, often quiet, that perhaps will swell, or build, in some way, as a means of taking a figurative breath before the song really begins the act opening up.

There is an instrumental break near the halfway point of The Greater Wings, and the second half of the record opens with what is, at least for me, the most lyrically poignant and striking track of this collection—“Lightning Comes Up From The Ground.”

And I had no doubt how affecting the album would be as a whole, but it was within this song that I did begin to grasp the seriousness, and the emotional gravity it is navigating with grace, and could begin to see the the space forming when the ideas of love and grief slowly begin to collide into one another, creating something that of course feels difficult or uncomfortable to sit within, but becomes a mirror held up to reflect portions of the human condition.

“Lightning” opens with a brief, shuddering wash of a low, synthesizer tone that does eventually blend almost seamlessly into the gentle finger-plucking acoustic guitar, creating a gentle, comforting drone that courses just underneath, and parts itself to allow the mournful, gorgeous, extremely subtle string accompaniment to slowly enter and punctuate when Byrne delivers the song’s titular phrase.

The song is certainly not the first place on The Greater Wings when Byrne is writing from an intersection of loss and longing, but I think this is the first time on the record where there is a rather visceral feeling of regret that hangs over all of it—perhaps it is the aesthetic of the song itself, because it is one of the more apparently bittersweet in simply how it is arranged, but it also comes from the way Byrne walks through these fragments, and how her voice allows specific words, or phrasings, to be extended out just a little more, with all of these elements coming together beautifully, sure, but in that beauty, there is a difficult to articulate the feeling of something awful that is nearly impossible to shake—of loss, and of love, but also of the things we do, or do not say to a loved one, and what it is like to now live in the moment knowing you will be unable to have the chance to.

In terms of the songwriting, and construction of “Lightning Comes Up From The Ground,” there are no real delineations between a verse or a chorus, but rather it is organized as one sprawling body that Byrne, gracefully, navigates through until the end.

“I wanna be a fantasy to you,” Byrne declares surprisingly and seductively in the opening line. “And I think that’s what’s going on here. Every time you come around—lightning comes up from the ground.”

There are some songs on The Greater Wings where the whole thing kind of works, or ends up hinging on a few lines, or a very specific phrase turn from Byrne, but the thing about “Lightning” is that in the unrelentingness with which it reveals itself where you wind up quite literally hanging, or in some cases, clinging and holding close to nearly every word.

“There’s no use to describe the sorrow of that time,” she continues. “I knew, even then, it was always meant to be the past. It was I who walked back and dragged it into the future; I who drove the road, and screamed into the night sky.”

It’s near the end of “Lightning” where Byrne utters one of the lines that did resonate with me the most, or that I saw a rather unflattering reflection of myself in the mirror she held up in front of me—“Death to the old ways—but who am I without them,” she asks, but it was the earnestness and sincerity of the third verse—a kind of fearlessness in a secret or a confession, that will stay with me the longest.

“That look is the most vivid image I have of you,” she sings, her voice gently coasting and wafting above the hypnotic acoustic guitar strings. “The voices in my blood alive with longing. I tell you now what for so long I did not say—that if I have no right to want you, I want you anyway.”

*

The thing about grief is that it doesn’t go away—not really, and there is no right or wrong way to do it, or any set length of time you “should” be allowed to do it for, but what I have come to have a much better of an understanding of over the last few years is that everybody carries their grief differently, and for different amounts of time.

I hadn’t thought about the coexistence of grief and joy in a long time, or the unfinished conversation around it, but I was reminded of this all recently in reading the book Faith, Hope, and Carnage, which is a collection of transcribed conversations between Nick Cave and writer Sean O’Hagan—it is ultimately a product of the pandemic, with Cave still feeling the disappointment of scrapping the tour he had planned in support of his moody album with the Bad Seeds from late 2019, Ghosteen, which was a meditation on the passing of his son.

Cave, himself, as a person and the persona he’s developed over his career, is objectively gloomy, or morose, but in that gloom, he’s also sharp and eloquent, which is apparent in how he converses with O’Hagan, and how even though at the time the interviews were conducted, when he was very clearly still stumbling through the grief of this loss, he has reached a point where he is not so much “at peace” with the passing of his son, or has come to terms with it, but has put in the work (his outlet with The Bad Seeds certainly helped) to grieve openly, but also to be reminded that in the face of death, or this kind of loss, that it is imperative to not let that open grief be all-consuming, and still look for the moments, or memories, however small or brief, of joy.

And friends, there is a flooding, or sorts, for me—perhaps for you, as well, if you are as familiar with grief as I have become within the last decade. The flooding that comes when you try to find that space where you have been assured that grief and joy can coexist. The flooding that comes because you still haven’t found it, and might never find it, and had ultimately forgotten all about it.

The flooding of sadness, or sorrow, that comes from the moment when you really feel, with the fiber of your being, the loss, and where that takes you; the flooding that continues when you try to push back against that with the fragments of joy that are clutched in your palms, which, I have found, is not always enough.

And those fragments cannot withhold the deluge when you, again, feel it with every fiber of your being.

And I no longer am as concerned with the coexistence of grief and joy as I once was, a number of years ago, not because I no longer believe that it is possible, nor is it because I no longer grieve. I think for some, it very well could be possible if they are able to find the balance where those two things collide, or coexist, I am just more confident now than I had been in the past that it is a balance I would be unable to strike.

The notion of platonic love most certainly found its way into things that I was writing about last year, and there is a high possibility that it had been a theme, however small or large, for a few years before that.

And in thinking bout this notion, I was reminded of both a quote from an essay by Hanif Abdurraqib about platonic love within the larger context of love, in all its forms, as well as something he had said recently to expand upon the sentiments.

Among other things that are discussed in the essay “Carly Rae Jepsen and The Kingdom of Desire,” which was published as a stand-alone piece online before it was collected within the fifth-anniversary edition of his book They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us, Abdurraqib talks about Jepsen’s song “Your Type,” from her 2015 album Emotion, and how, when introducing it at a live performance, states it is about being in “the friend zone.”

“Platonic love is vital, essential, and perhaps the one thing left in this wretched landscape that could save us all for a little bit longer than we deserve,” he wrote.

In describing the essay as a whole, or perhaps just elaborating a little bit more on the portion of the essay that quote, specially, has been extracted from, Abdurraqib implied we could, and should, treat platonic love with the same generosity and rigor as romantic love.

“There are so many ways to fall for someone,” he continued. “If you are at the edge of the cliff anyway, consider taking the leap. The ground might be soft enough to hold you and whatever comes next.”

The Greater Wings is, of course, an album that is about so much more than the intersection or convergence of love and grief, and what happens within the space of those two things slowly coming together, but I think what is more compelling to me now, and what is unpacked more thoughtfully, is how Byrne writes about the kind of love—the deep connection—that she had with Littmann.

And so much of this has been framed, at least at this point, as we head into the conclusion, around the idea of platonic love, because it is an album that is written, throughout, from a place of earnestness and sentimentality, which are things that we should not be so quick to downplay or not be receptive toward.

Because I am thinking about how in love, regardless of what kind, there is a fear, or an uncertainty, or an uneasiness, in how you talk about it, yes, but also when and how you share those sentiments with another. And the fear, or the uncertainty, about what will be said, if anything, in return when you tell someone that you do love them—the fear that it won’t be reciprocated, or received with the sincerity with which it was declared.

The fear, then, does keep us from the admission of love within this kind of close friendship.

If you are at the edge of the cliff anyway, consider taking the leap, because there will be a moment when you have become close enough to someone, and the two of you have been earnest enough with one another, and have become comfortable enough, and have opened up enough, that the fear, or uncertainty, has disappeared and the ground is soft enough to hold you both, and whatever comes next.

And I am thinking about the idea of platonic love, or at the very least, the kind of intrinsically close connection that people can share, because you can ultimately feel, or rather, hear, that kind of affection woven tightly into The Greater Wings. It is an album about love and loss, yes, and certainly where those two things are unable to outrun one another, and the parts of The Greater Wings that do take place within Byrne’s grief are certainly compelling and are often as beautiful as they are harrowing to hear, but it is the moments on the album where Byrne comes up for air, and reflects as she is able to on the kind of connection she and Littmann shared as creative partners or collaborators, as friends, and during the time they were romantically involved.

The album’s longest song, and perhaps its most chilling—both figuratively and literally, is its closing track, “Death Is The Diamond,” and the intro, or very deliberately paced opening, is slow and icy, with dissonant string instruments swirling and scraping, before the contemplative piano progression arrives and then tumbles out into the atmosphere.

Byrne, as a performer, has worked within sparsity or a kind of skeletal arrangement in the past, but “Death Is The Diamond” is the first time when you can feel a loneliness, and a longing, that is never going to go recede—it’s both gorgeous to hear the way she plays with these emotions in the soulfulness and melancholy in her voice, and how it echoes into the distance behind her, and with the way she presses her fingers down onto the keys of the piano—but it is also utterly devastating.

“Blue dawn of night, go on,” she implores in the opening line, which is delivered with a heightened sense of fragility in her voice. “I’ve been missin’ you now with my whole life.”

The thing about grief, or loss, is that there are often no answers provided in the end—easy, or otherwise. Sometimes, it leads to additional questions, but more often than not, at least in my experience, there are just a lot of things unresolved, or unsaid, and questions that are unable to be answered.

There is a reluctant acceptance you have to make, regardless of how much you might simply not want to, or reject the very idea of.

“Death Is The Diamond” doesn’t offer up any answers, but instead, it is Byrne attempting to find that reluctant acceptance as gracefully as she can.

“And if need be, I will carry your death wish,” she continues in the second verse. “Back into the arms of this rare life. My back to your back—this has been no easy religion,” she says. “Written, braided, lived, and tried.”

In its third verse, the song finds Byrne painting a portrait of her life, and love, with Littmann that is evocative through both fragmented imagery as well as an earnest declaration—“Sign on Caravan East reads ‘For You, Anything,’” she says, making a reference to a club in New Mexico. “I guess it’s a story so much greater than our own. Alive, moving through dusk. Alive, if only once—you made me feel like the prom queen I never was.”

The song’s chorus is where, as she is able, Byrne reluctantly concedes to the loss, and the grief. “Let the sun go down,” she pleads. “I don’t want to feel anything but the moving ground. Death is the diamond…I guess sometimes it doesn’t always happen when you’re tryin’, oh, but when you’re livin’, it comes on out.”

We remember, as we can, and how we can, the life. We try our best not to dwell on the loss.

There is this idea that grief and joy can coexist. And I did surprise myself, in sitting down with The Greater Wings, to realize that this was an idea that I had not thought about seriously in quite some time. Because the reality is, regardless of if I believe that those two things can coexist, and that there are people who find that place, or that balance, I am uncertain if I ever would.

And I think I’m okay with that now—more okay than I thought I would be with that kind of admission.

Within the intersection, or convergence, of grief and love, Julie Byrne is asking that you make space, as you are able, for her and the heartfelt reflections on The Greater Wings. Byrne returning to music after half a decade would have been welcome no matter what kind of album she wanted to, or in this case, needed to make, but this album is an enormous, confident, heartbreaking, and gorgeous artists statement—utterly flawless from start to finish, and within the space she asks you to make for her, and her memories of Eric Littmann, Byrne provides something that is absolutely transfixing and unforgettable.

1- It was going to be too difficult, or perhaps just distracting, to try and list these songs within this piece, but I am thinking of the different reads you can have on “Anything” by Adrianne Lenker, “You Said Something” by PJ Harvey, “Sing Your Heart Out” by Camp Cope, and arguably "Anywhere With You," by Maggie Rogers.

The Greater Wings is out now via Ghostly.