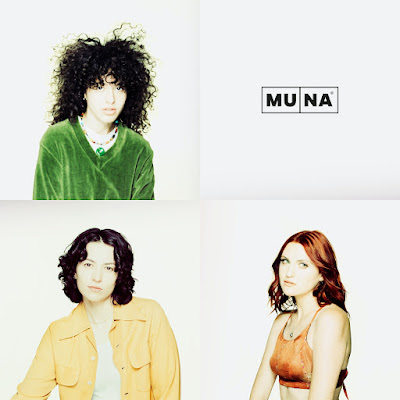

Album Review: Muna - S/T

And it has to be intentional, I think, the way Katie Gavin sings the word “dandelion” at the end of the second verse in “Kind of Girl,” right before the song effortlessly builds itself back up into the enormous chorus.

I am uncertain if it is regionally specific, or perhaps just the Illinois accent that I have not yet been able to lose entirely, but if I were to say the word “dandelion” out loud, I would, and have, pronounced it “dan da lion,” with an emphasis on the second syllable.

But in “Kind of Girl,” as everything begins to swell, Gavin, without hesitation in her voice, pronounces it as “dandy lion.”

I’m a girl who’s blowing on a dandelion thinkin’ how the winds could change at any given time.

And it has to be intentional—the way Katie Gavin sings the word “dandelion,” as is the intention behind how the entire song is structured—“Kind of Girl” knows just what instruments to use and when to bring them in—like the mandolin that makes an appearance in the chorus, or the dramatic inclusion of a string section—and it’s the kind of song that knows when its arranging should reach an emotional peak that is just on the cusp of becoming entirely too much, but never tips itself completely over the edge.

But what isn’t intentional, at least I do not believe so, is the effect Gavin’s pronunciation of “dandelion” has, because there is something inexplicably heartbreaking about it—it is not more heartbreaking than the song as a whole, however. But it is simply more heartbreaking than the pronunciation of a single word should be.

*

I have found that what interests me, specifically in music, and even more specifically—in writing about music, is what happens, or what is created, in the spaces that form when there is a convergence.

And I had not considered this kind of convergence before, until somewhat recently, when I was listening to the Maggie Rogers song “Light On,” from her major-label debut, Heard It In A Past Life, and understood it was the kind of song that cultivates feelings from two different places, and that the song itself is the space where those two things end up converging—musically, it is borderline triumphant at times, especially within the heights, the chorus grows to. Still, it’s also a song that, even in its verses and the moments that lead up to that anthemic chorus, is uptempo and dazzling to hear.

But the contrast comes in its lyrics, which are not exactly “devastating,” but it is an emotionally charged and highly personal reflection from Rogers, and how difficult it was for her to initially navigate her very sudden rise to fame, while trying to maintain a connection to those who were supportive in the past, and accept, however hard it might be to do so, if those connections might wind up being severed along the way.

“If you keep reaching out, I’ll keep coming back. And if you’re gone for good, then I’m okay with that,” Rogers sings with a mix of immediacy and desperation within her voice. “If you leave the light on, then I’ll leave the light on.”

I had heard the song “Light On” several times before I came to recognize what was happening—this specific kind of convergence and it was when I heard the next line in the chorus, that I had an understanding—“And I’m finding out there’s just no other way that I’m still dancing at the end of the day.”

And the understanding is of the notion of catharsis through pop music—and that a song like “Light On” exists in a space where you want to both flail around wildly to the music in the darkness of a dance floor, lost in a moment, and give in to the emotions you are attempting to outrun, and simply just cry.

Muna’s new self-titled album, their third full-length and first since linking up with Phoebe Bridgers’ imprint Saddest Factory, operates within this space—like, the album, across its 11 tracks and taken as a whole, is a perpetual give and take of extreme highs and lows, but there are also specific songs, or moments within songs that finds the trio working within that very idea of catharsis through pop music—the tension and release found within the urge to oscillate and sway to the music, and collapse in a heap on the floor sobbing.

*

Muna is entirely deserving of the success that they have found within the last year, following the announcement of their signing to Saddest Factory, the release of their undeniably infectious single, “Silk Chiffon,” which boasted a guest turn from Bridgers herself, along with the slow rollout of singles leading up to the release of Muna—but before last year, the group was not “unsuccessful,” per se. Still, it has taken time for Muna to arrive where they are now.

They were founded roughly a decade ago when the three members of the group—Katie Gaven, Josette Maskin, and Naomi McPherson, met while attending the University of Southern California. Per the group’s Wikipedia, McPherson and Maskin and already been playing music together (allegedly ska and prog rock) before they began collaborating with Gavin—the earliest results of which were distinctively pop-oriented.

After self-releasing an EP through Bandcamp and Soundcloud in 2014, Muna signed with RCA Records to release an additional EP in 2016, followed by two full-lengths: About U in 2017, and two years later, Saves The World. And in both the profile on the band and Muna that Stereogum published before the album’s release, and in the extremely backhanded review Pitchfork eventually ran, both state RCA had dropped the group following the release of Saves The World—with the group’s New York Times profile adding their relationship with the label ended during the early part of the pandemic as a “cost-saving measure.”

I get the impression that even with an opening slot for Harry Styles, an appearance at the 2016 Lollapalooza festival, and albums that did well enough upon release to have landed within the top 10 of the Billboard “Heat Seekers” chart, that RCA, as major labels often are, was at a loss on what to do with Muna in terms of actual support or promotion—so I am uncertain if they were ultimately grateful to be free from their deal, or if it was a tumultuous severing.

And I stop short of saying that there is irony found within Muna’s recent rise in popularity since connecting with Bridgers and her imprint—a subsidiary of Dead Oceans which itself is a subsidiary of Secretly Canadian, but it is very apparent that with more creative control and autonomy over their music—all three members of Muna are credited with producing and engineering the record—the group was able to make the album that they wanted to make right now in their career, which is ostensively the culmination of a decade’s worth of work, and a testament to the growth and development of the band’s sound and songwriting.

An absolute rollercoaster ride of emotions, the short answer about Muna, an album, is that even when it plunges you into difficult personal reflection or heartbreak, it is more fun than legally allowable.

*

In an unsurprising turn, Muna sequences “Silk Chiffon” as its first track, which some might view as an audacious move, or the group playing its hand entirely too soon. Because outside of placing it at the top of the album, there is a slight risk involved with including it in the tracklist, simply because of the nine months of life it has already had.

I am remiss that anyone out there has grown tired of hearing it, but within the way, music is consumed. With the unfortunate but almost unavoidable demands placed on artists to pump out new material to remain relevant continually, some listeners might not be as enthusiastic about going backward, albeit slightly, before pushing forward, and hear a song that they already know so well.

There is no shelf life to a song like “Silk Chiffon,” though, and with its inclusion on Muna, I am reminded slightly of my initial, and minor, concerns over Olivia Rodrigo’s “Driver’s License.” Initially released in January of 2021, it had taken on a life of its own by the time it was included on her debut album, Sour, which arrived in May. By the end of that year, when I was thinking about its impact, I wondered if it was a song I had, perhaps, burned myself out on and that it was not one of my favorites from the last 12 months—but I had not, and it still very much was.

With the life that “Silk Chiffon” already has been given—it, also, was one of my favorite songs of 2021; the fact that it is the opening track on Muna is like a warm, jubilant welcome by a familiar friend. In roughly three and a half minutes, it is bursting at the seams with a kind of rollicking, shimmering exuberance that I, as a listener, would never grow weary of listening to.

Late last year, when I was reflecting on “Silk Chiffon,” what I said was that no pop song should be this perfect; I still stand by that, and the first note I took when sitting down with Muna from start to finish was “Does this song have the right to be this bombastic and this flat out enjoyable?” And within the context of the album as a whole, “Silk Chiffon,” though in the context has some competition for the title of “pop music perfection,” and even if Muna does outdo itself time and time again throughout this record with the way they continually craft jaw-droppingly impressive pop tunes, “Silk Chiffon” still hits—it still hits just as hard as it did last year. It still hits because I do not actively seek out much music that one would consider “fun” to hear, but it’s the kind of song that puts an enormous smile on your face that you can’t rid yourself of. It’s the kind of song you can’t help but want to dance to once the hypnotic delivery of the “pre-chorus” rolls in, as Gavin utters the phrase, “Life’s so fun,” like a mantra—and I hadn’t even considered it until recently how audacious of a statement that was for the group to make during the times we are living in.

It still hits because no matter how many times you have heard it, you still want to shout the titular phrase, taking an enormous breath in-between the two words, when the song slides into its enormous chorus. And it still hits in just how effortlessly and breezily it captures the flirtatious nature of a new relationship, or simply when you are deep within the encompassing jitters of having a crush. Sapphic enough to get to the queer romance at the heart of the song, but universal enough in how its ultimately written that it remains accessible (both in its arranging and lyricism) to anyone who has felt compelled to body roll in time with the way Gavin playfully sings “Life’s so fun,” or to anyone who has experienced the jittery mix of anxiety and excitement if someone has turned around and given them that “you’re on camera smile.”

*

Muna headed into the making of their self-titled album with a “no filler” kind of mentality—“I just knew that my perspective was to make…an album of bangers,” Naomi McPherson is quoted as saying in an interview with Atwood Magazine. “If it doesn’t bang, it’s not going on the album!,” and for, like, almost the entire record, they stuck to this philosophy—and the thing about Muna is that, even in the moments when it is slightly less successful (there are two songs specific that come to mind, tucked into the back portion of the record) they are still extremely listenable; there’s no truly “bad” song the be found.

With the way the album is structured, jumping off from a massive opening like “Silk Chiffon, it’s clear that the trio is operating with an intelligence to have an understanding of the give and take a collection of songs like this needs to have—when to kick it up and become even more exuberant, or when to dial it back and create a simmering, often skittering sense of tension.

Once the record gets underway, there is the fascinating juxtaposition that occurs early on in between the album’s second and third tracks—the kaleidoscopic, hedonistic “What I Want,” which was released as the fifth single from Muna, the same day that the album arrived, and the third track, the glitchy, heavy, electro-infused “Runner’s High,” which is one of the most surprising and compelling moments on the record.

As a whole, Muna is not exactly a concept album, but the more time I have I’ve spent with it, it became clear how interconnected a lot of the thematic elements are, and how the album is constructed to tumble from one emotion to the next—often as a means of depicting the contrast between the two, and often with little, if any, breathing room from one to another.

There are myriad iconic, quotable lines throughout the record, some of which are dramatic enough to make you wish you still needed to set an away message for your AOL Instant Messenger; others are done with a real sense of humor. And one of those lines—the ones that will elicit a hearty, genuine laugh at how earnestly it’s delivered, comes in the chorus to “What I Want,” whereas she details the night of excess she’s seeking, Gavin bellows, “I wanna dance in the middle of a gay bar.”

Set against the sultry backdrop of a writhing, synth-pop-inspired arrangement, “What I Want” is lyrically an exploration of wanting to live in the moment—the moments depicted here often being of lust and excess. “When I go out again, I’m gonna drink a lot,” Gavin exclaims in the song’s opening line. “I’m gonna take a shot ‘cause that’s just what I want.”

“And when I see my friend put something on her tongue, I’m gonna ask for one,” she continues.

As “What I Want” slithers into its second verse, Gavin turns her attention from alcohol and recreational drugs to a woman, dressed in leather, on the dance floor—“I think we’ll get along, ‘cause she’s got what I want.”

And there is a propulsive nature to both “What I Want,” and “Runner’s High,” both lyrically and musically speaking, but they couldn’t be more different when compared. “What I Want” is pushed forward by a desperate urgency rooted in unbridled desire, which oozes from every note of the song; “Runner’s High” is pushed forward by a different kind of desperate urgency—to escape the past.

It shouldn’t be a surprise that Muna is not an inherently “dark” sounding album—why would it be? It’s a bright and extremely queer pop record. But there are moments where a shadow is cast, and one of those is the explosive, dizzying “Runner’s High.”

In stark contrast to the seemingly unquenchable thirst for debauchery from “What I Want,” “Runner’s High” opens with Gavin singing pensively, “Since I’ve left, I’ve not been drinking or staying out late.” The song, which isn’t necessarily a “breakup song,” but rather a reflection on what happens well after the breakup is over, spirals from a place of brooding tension during the first verse, and even through the chorus before the instrumentation detonates with thundering bursts of percussion and throbbing, buzzy synths.

The shadowy tone of “Runner’s High” is both present in its structure and instrumentation, yes, but it’s also in the lyrical turn it takes—creating a far cry from the technicolor, carefree whimsy of “Silk Chiffon.” “Moving fast so you can’t cross my mind—sometimes I wonder if I’m on a runner’s high,” Gavin utters with the chaos of the chorus. Then, a few lines later, she changes the lyric to “Since I ran out of you, I’m on a runner’s high,” a brief but vivid lyric that only adds to the frenetic urgency of the song.

If “Runner’s High” is operating from whatever kind of dark corners lurk at the edge of Muna, “Handle Me,” which opens up the album’s second half, is also, at least partially, coming from a similar place. It is the quietest song on the album, and the one where the group shows their ability to create a smoldering sense of restraint. There isn’t a tension that is waiting to burst and be released, but a circling sense of pensive reserve, set to a groove that slinks along thanks to the drum machine programming and bouncing acoustic guitar string plucks, as Gavin sings her lyrics with an icy, robotic effect trailing under her voice.

*

There was a time when an album—specifically a pop album, was designed to house five or six singles, released slowly over time until the artist opted to release another album—e.g., Michael Jackson’s Bad, is 10 songs—11 if you count “Leave Me Alone,” which was initially only available on the album’s CD release; eight of those 11 songs were released as singles between 1987 and 1989.

With the band’s insistence on creating an album full of bangers, the longer you spend listening to Muna (at 39 minutes, it does easily welcome subsequent and repeated listens), the more it becomes clear that there are bangers for days, yes. Still, there are also songs where the trio went above and beyond to craft a bombastic, infectious pop song, that was ultimately designed to be released as a single.

By the time Muna was released as a whole, roughly half of the album had been issued in advance, and once you listen to the album from beginning to end, it is clear to see why these songs were the ones selected to represent the album, and the band, early on.

Arriving in the final third of the record, “Anything But Me,” the second of the five advanced singles from the album, takes the formula for an exuberant, shimmering pop tune and runs away with it, creating a brilliant homage to the kind of songs from the late 1980s and early 1990s that effortlessly merged pop and R&B together.

And it is on “Anything But Me” where Gavin delivers one of the other iconic, humorous lyrics from the album within the song’s opening line—“You’re gonna say that I’m on a high horse,” Gavin deadpans. “I think my horse is regular-sized.”

If a song like “Runner’s High” is a contemplative, somewhat remorseful glance back in the literal and figurative rearview that comes after a breakup, a song like “Anything But Me” is a long, hard stare at the relationship itself, and the person you were involved with, after a lot of time has elapsed, but the feelings of resentment have not receded. And for the humor found in the song’s opening lyric and the lines that follow, the rest of the song is written with a snarling embitterment. “All I wanted was somebody honest living for more than their next good time,” Gavin declares before the song slides into the sing-a-long ready chorus. “But it’s all love, and it’s no regrets,” she continues. “You can call me if there’s anything you need—anything but me.”

“Anything But Me” is not exactly the last grasp of exuberance before the album reaches its final two songs, but it is the last place where there is a song operating at this high of a level of pure pop music—and structurally, Muna is the kind of album that is honestly relatively front-loaded with some of its best and most emotionally impactful material.

If you look at “Runner’s High” and “Anything But Me” as two extremes in how someone might feel, or at least, react in the aftermath of a breakup—ultimately trying to outrun any regrets you might have about your choice, or still tightly clenching the resentment that lingers, a song like “Home By Now” occupies the space in between those two opposites because it ruminates on the question of “What if.”

Less overtly bombastic and blindingly bright in its arranging than “Anything But Me,” “Home By Now” is simply just a better song in terms of the material found on Muna to be plucked as advance singles, and among one of the finest moments on the record (and there are certainly a lot of those to choose from.) Released as the fourth tune before the whole album’s arrival, it is a wildly infectious and technicolor collision of beauty and heartbreak.

And yes, while “Home By Now” occupies that space in between the contrast in emotions after the dissolution of a relationship, it is also among the tunes on Muna that find themselves offering a form of catharsis through pop music—not totally occupying what happens in the convergence between losing yourself on the dance floor and losing it on, like, your bedroom or bathroom floor, but it occupies it just enough that it, in that catharsis through pop music, it is one of the few song songs on the album that are genuinely effecting—like, frisson inducing, tears welling in eyes impactful.

Against a slinking, pulsating synthesizer and steady, electrified drum beat, “Home By Now” pensively simmers in its verses as Gavin reflects on a relationship, long since over; by the time the dazzling chorus arrives, both the restraint with which she was using before in her voice, as well as in the instrumentation’s structure disappear as “Home By Now” takes off into a gigantic, devastating chorus that dwells not in if the wrong decision was made, but simply what if things had not ended the way they did.

“Would we have turned a corner if I had waited?,” she asks at the beginning of the chorus. “Do I need to lower my expectations? If we’d keep heading the same direction, would we be home by now?”

And yes, many of the album’s iconic, and even quotable lyrics find themselves rooted in the band’s sense of humor, but “Home By Now” is one where Gavin’s capability to turn a solemn, personal phrase becomes extraordinarily apparent as the chorus continues—“Now I don’t know if I’d been okay with holding out hope for your stack of rainchecks. If I’d been able to grin and bear it, would we be home by now?”

*

Because Muna is an album built around the very notion of the banger, it is more or less unrelenting in its energy from song to song. And yes, there are places where it can pull itself back slightly w/r/t its exuberance, for a few quieter moments, but rarely are there places where it is somber, or melancholic, except for the penultimate track, “Loose Garment.”

And what I am uncertain about “Loose Garment,” is if I have just spent entirely too much of the last two years listening to pop music and being in my feelings, or if the opening line is an allusion, no matter how slight, to “August,” from Taylor Swift’s Folklore.

On the soaring, vivid, and bittersweet “August,” Swift sang in the song’s chorus, “August slipped away like a bottle of wine—‘cause you were never mine.” And here, even before the song got underway during my very first listen, when I heard Gavin quietly sing the song’s opening lyric, “I knew before it started, this August would be a hard one,” I had the suspicion that “Loose Garment” was about to be something to truly behold.

And perhaps the fascinating thing about “Loose Garment” is how, from the moment it begins, the song’s arrangement does not give off the impression that it is going to be one of the most dramatic and emotionally charged songs of this set—the bassline slithers in and finds its groove immediately, with glitchy percussion clacks around underneath. It isn’t long, though, before airy, melancholic synths are brought in, along with a stirring string accompaniment—it’s then that the actual tone of the song is revealed.

“I’m broken-hearted—I’m disappointed. It was still beautiful,” Gavin laments as the song’s first verse continues to build. “Took myself out to dinner and cried about you on the way home.”

And I am uncertain how long ago I began doing this, but there was a point several years ago where I came to understand the physical manifestation of what living with depression felt like—like somebody was strangling me. Like an actual tightening that I could feel in my neck and chest, often coupled with being more or less immobilized by the crushing weight of sadness.

And perhaps that is the reason why “Loose Garment” is one of the most personally affecting songs on Muna—because of how seen I felt by the time the group reached the song’s chorus: “Used to wear my sadness like a choker,” Gavin confesses. “Wrapped around my throat.”

“Tonight, I feel I’m draped in it, like a loose garment—I just let it flow.”

“Loose Garment” is absolutely mesmerizing in the kind of energy it conjures—the throbbing of the rhythm, the billowing, mournful sweeping of the strings, and the visceral sorrow of Gavin’s reflective lyricism create a song that thrives within a moment of simmering tension that, even as the song gently brings itself down into a conclusion, is never really released, or gives in to the need for resolve.

*

Muna is an album that is full of surprises—opening with the surprise that yes, life is still fun and that “Silk Chiffon” is still just as exultant to hear now as it was almost a year; or the surprise that Muna is able, and they make it seem effortless as they do, to continue to double down on the unabashed fun throughout; or that the album, in all of its kaleidoscopic, shimmering pop glory, can take unexpected, inward, and shadowy turns.

And perhaps the most surprising thing about Muna is the song’s centerpiece, concluding its first side—“Kind of Girl.”

But what is the most surprising thing about the song “Kind of Girl”?

Is it the way—it has to be intentional, I think—Katie Gavin sings the word “dandelion” at the end of the second verse, right before the song builds itself back up into the enormous chorus?

The way she sings it, without a shred of hesitation in her voice, pronouncing it “dandy lion.”

Is it the way she sings that word, and that word alone, and the more than likely unintentional effect it has on me as the listener?

Or is the song itself as a whole—not just one moment out of so many, but all of them, and the power and beauty it has?

The thing that is obvious about “Kind of Girl,” right from the beginning, is that it is both unlike anything else on the record, and that is Muna’s take on a country song—especially a pop-leaning, slow-burning country song—not a ballad, but close, from the late 1990s or early 2000s, when the lines between genres were slowly beginning to blur.

“Kind of Girl” is also unlike anything on the record because it is one of the few songs that are not directly about a relationship—either the flirtatious early stages of one, the sorrow that comes in its aftermath, or simply the hunger and lust that you find yourself filled with when someone on across the crowded dance floor catches your eye. It is inherently a song about radical self-acceptance—however difficult or seemingly impossible that might be.

It’s about the forgiveness, kindness, and graciousness we often either are unable to or simply forget to show ourselves, despite the understanding we need to.

And I say that “Kind of Girl” isn’t directly about a relationship because it lacks the kind of narrative antagonist that songs like “Runner’s High” and “Anything But Me” has. But what it does explore, and does with surprising honesty, is the reasons relationships in the past might not have lasted—and how the multitudinous nature of Gavin’s assessment of herself contributed to that.

“I’m the kind of girl who takes things a little too far,” Gavin begins quietly in the first verse. “Who presses a little too hard—that’s why you left a mark.” She continues her self-effacing reflection in the second verse, where she describes herself as a girl who is likely to drive her partner “insane,” and refers to herself as “restless” and “a little in love with the pain.”

But it is also in the song’s second verse, and in “Kind of Girl”’s extremely theatrical and soaring chorus, where the implication of how vital self-acceptance is is introduced. “I’m the kind of girl who owns up to all of my faults,” Gavin belts out. “Who’s learning to laugh at ‘em all like I’m not a problem to solve.”

She is a girl blowing on a dandelion, thinking how the winds could change at any given time.

And I hesitate to refer to “Kind of Girl,” specifically the chorus of the song, as being emotionally manipulative, but if I were to say that, I mean it in the best way possible—because Muna had to have an idea of what they were doing, and what it would do to the listener, when this song was put together. There is a dramatic swelling of the song’s instrumentation, and even more theatricality to be found in the phrase turns used, like “Yeah, I like telling stories, but I don’t have to write them in ink—I can still change the end.”

And it is in the chorus where the song’s conceit, source of tangible hope, and emotional power is located—wrapped in the country-tinged instrumentation: “I could get up tomorrow, talk to myself real gentle—work in the garden. Go out and meet somebody who actually likes me for me, and this time I’ll let them.”

I am uncertain when I began connecting a certain, very vivid feeling or sensation to specific songs—or at least specific moments within songs. It can be difficult to articulate with any clarity, but an example that I can give is from “The Geese of Beverly Road” by The National; near the end of the song, when the music is building and the repetition of the line, “We’re the heirs to the glimmering world.” There is something about that specific moment—the imagery, the lyricism, the way the music is swirling around—it feels like you are soaring, and it is both beautiful and devastating in the best way.

And there are, of course, many reasons why “Kind of Girl” is the kind of song that has the emotional pull it does, but its ability to craft this vivid feeling is one of them—it is not a feeling of soaring, though. When “Kind of Girl” hits its scream-along chorus, especially the second time around, it gives the feeling of running.

Both running away from and toward yourself.

*

Of all the emotions that Muna explores, it saves a palpable kind of longing, or yearning, for its stunning conclusion.

Similar to how several tunes on the album are structured around having the potential to be released as singles, it is apparent that “Shooting Star” was arranged to be the finale. Building itself up from a glitchy acoustic guitar pluck and minimalist, pulsating rhythm, the song reaches a point where it explodes in a torrent of pounding drums, layers of synthesizers, and dreamy electric guitar.

“Shooting Star” is musically torrential, yes, but it is also the last plummet on the album’s emotional rollercoaster of lyricism—exploring the way your feelings, despite your best efforts, can get ahead of you—or even away from you completely. “I know I only just met you, but you’re already spanning skylines inside my mind,” Gavin admits in the song’s hushed first verse.

In a sense, the sentiment in “Shooting Star” is the inverse of how the album began, with the playful, light nature of “Silk Chiffon.” Here, the implications are that the feelings are mutual, yes, but more than that, they are drastically unbalanced, and as Gavin’s lyrics continue to unfold, she, with arresting accuracy, goes into detail on why it’s called “a crush.”

“Tonight, when I closed the door, I wanted to turn back, but when I see a shooting star, I stay out of its path,” she sings in the chorus. “And that’s what you are—you’re so bright. You burn my eyes, and you move too fast.”

The sense of yearning and longing—of wanting and being unable to have, or wanting, and just being out of your grasp, culminates in the song's final lyrics, and it’s this unresolved, genuine sense of emotional unrest that ends the album. “I wish I may, and I think I might regret this either way—if I write you in my heart or keep you in the dark,” Gavin concedes. “So I’ll love you from afar.”

Muna is nothing short of incredible—a practically flawless album that occupies that space between letting yourself go and flailing to the music, whether on the dance floor or in your kitchen, and letting it go and sitting with the uncomfortable feelings we spend a majority of our day trying to stay one step ahead of. Through this collection of songs, Muna gives voice to both of those, and the difficulties found within the give and take between how much of yourself is spent in either state.

Early on, when I began writing about music, and opening myself a little more to genres that were outside of what I would usually listen to, I would use the expression “pop music for adults” to describe certain things—because, at the time, I did not believe that pop music as a whole was for people outside of a specific demographic.

Muna is an album that, in the end, is for everyone, because it is pop music about the human condition. It’s a bold and often fearless statement and a gigantic artistic leap forward for the trio—for having departed a major label, and in finding a home with Saddest Factory, it is the kind of slick, glistening record that doesn’t sound like it’s the product of anything independent, which is thanks to the closeness that Maskin, McPherson, and Gavin have with one another as bandmates, and how much they’ve grown in confidence as writers and musicians—the album’s liner notes, while densely compressed onto one side of the LP’s inner sleeve, reveal the impressive, multi-instrumental nature of everyone in the group.

Heartbreaking in places—both unexpected and not, rarely is an album this much of a joy to listen to. Even when everything is telling you otherwise, Muna believes in the mantra it casts within its first few minutes—that life, really can be, so fun.

And for 40 minutes, it wants you to believe in that too.