Concert Review: Arooj Aftab, The Parkway Theatre, April 10th

And I am uncertain, now, at this point, how far along into working with my new therapist I was when I showed up for one of our meetings—all of them conducted virtually, of course, because of the ongoing state of the world—wearing a Carly Rae Jepsen t-shirt. I was not anticipating her reaction to the shirt—gasping, then blurting something about how much she loves Jepsen, and how, before we got into, like, my debilitating depression and things from my childhood it would behoove me to unpack and process, she had gone to see Jepsen perform in early July of 2019 at the State Theatre.

And at that point, the last concert I would have been to was, also, in early July of 2019, and retrospectively, I have often thought about how I, perhaps, had selected the wrong concert to attend because from a window seat in a restaurant in Downtown Minneapolis that I do not remember the name of, I watched a steady stream of people filing into the State Theatre to see Carly Rae Jepsen, who was touring in support of her then recently released album, Dedicated.

My wife and I, dining with my former boss and her husband, after we finished our meal, were going to the 7th Street Entry to see Foxwarren—a four-piece fronted by the beloved and marginally idiosyncratic singer and songwriter Andy Shauf. The group was touring North America for the first time in promotion of its self-titled debut album, which had been issued near the end of 2018. There was not a lot of overlap in the Venn diagram that mapped my taste in music and the taste of my former boss, but much to our mutual surprise, Shauf was one of the artists we shared a common interest in, specifically his high concept album from a few years prior, The Party.

Foxwarren, as a live band, cramming themselves onto the narrow stage of The Entry, were fine. It was a fine concert. And, maybe, like the dinner we had shortly before wandering over to the venue in the extremely humid and somewhat overcast evening in Minneapolis—maybe the show, retrospectively, was a little underwhelming and a little unmemorable. Foxwarren, with one album to their name, were playing literally the same set every night of the tour—the 10 songs from the LP, along with four “new” or at least unreleased tunes that they (at least that night) neglected to introduce by name to the audience, then one obligatory encore from Shauf, alone.

And live performances can, of course, go many ways—they can be disastrous or absolutely incredible, and the songs themselves that the artist performs can, of course, go many ways as well. A song can be played exactly how it sounds on the recording, or it can have taken on a new life, or grown in some way, to make something familiar suddenly become more compelling or surprising to the audience.

Foxwarren’s tunes had not taken on new life, or grown—the 10 songs from the album sounded almost exactly how they did as the vinyl spun on my turntable, and I don’t think the band was bored, or disinterested, but they were not exactly enthusiastic or charismatic on stage.

Maybe they were just really concentrating. Or trying to focus.

I knew a handful of people who were going to see Carly Rae Jepsen that July night in Minneapolis—many of them were folks that I follow and have a casual rapport with on what I refer to as “Minneapolis Twitter,” but some of them were also people who I actually, like, know from “real life,” and the next day, short video clips and photos begin to surface, and more than a year later, when it comes up in therapy, as our faces greet one another through our respective computer screens, and as my therapist’s face lights up in excitement when she reads the large, colorful letters printed onto my white t-shirt, she exclaims how much she loves Carly Rae, and how much fun she had seeing her at the State Theatre.

And I tell my therapist, before we get into, like, my debilitating depression, or the anger issues I was certainly having during that time brought on by my work environment, that I knew a lot of people who had gone to that concert, but I was just up the street, seeing a different act on a different state and retrospectively, I have often thought about how I, perhaps, had picked the wrong concert to attend that night.

*

When I moved from Dubuque, Iowa to Northfield, Minnesota, over 15 years ago, there was still a novelty to the fact that I was relocating somewhere so close to a major metropolitan area—a large city with myriad concert venues that attracted artists and performers I wanted to see. And what I am uncertain of, though, is when that novelty began to wear off, and when my enthusiasm was replaced with what I commonly call “concert anxiety.”

It’s a strange relationship I have with the idea of traveling up Highway 35 from our small town to the big city to attend a concert—I, overall, like the idea of it. I like the idea of a concert. Like, the notion of them as a thing in a very abstract form. I like the idea of going to see a performer I like, or admire, in person, and hearing the songs that have moved me somehow, or that I simply just enjoy, being conjured up right before my eyes, and ears.

I am, famously, or at least famously to the people who know me personally, severely depressed. And so, like, even if I appear to be interested in the very notion of something (e.g. concerts) the chance of me actually maintaining that interest, and being invested in something (e.g. again, concerts) during the moment when that something is finally happening is extremely slim. My severe depression, which has more or less taken the joy out of almost every facet of my life, then combines with the concert anxiety—and this pairing leads me to a slow spiraling and unraveling in the days before the event in question, and to a much faster spiraling and unraveling in the hours prior.

And I suppose the largest source of concert anxiety stemmed from my concern over whatever companion animal we were living with at the time—my wife and I lived with rabbits for several years, and I often felt guilty about leaving them alone in the house for an evening, and often would try to find someone to check on them and keep them company for a few hours. And even if I were to find a sitter for the evening, I was still worried—worried something would go wrong and the sitter wouldn’t know how to handle it. Or worried that the sitter wasn’t just taking good enough care of them.

And the truth there, though, is whomever the companion animal—rabbits, a cat, or a dog, probably were not all that upset if we were away from the home for a large chunk of the evening; this is more than likely me projecting my own emotions, or worry, on to them, and that projection is that they were sad, or lonely, without us there.

This projection is something it might also behoove me to process and unpack.

There is the commute—sometimes the trip from Northfield up to Minneapolis doesn’t seem all that long, or bad. The trip up to the concert is usually not the problem. It’s the drive back, often extremely late at night when you would prefer to be sleeping, rather than sitting in a car, speeding down a dark highway, ears more than likely ringing.

There is the difficult nature of navigating the Downtown streets of a large city—often congested with traffic and labyrinthine one ways to weave your way through. There is the act of finding a place to park—a parking ramp, or garage, is preferred of course but will I be able to secure a spot near the garage’s exit, so that getting out, and back onto the road at the end of the night is relatively easy? Or will we become stuck in a long line of cars, all trying to depart at the same time, trudging along slower than a funeral procession while I inhale the inescapable fumes of exhaust from the cars in front of me as well as behind me?

Will I misplace the ticket I need to use to pay for my parking spot? What if the show goes on so late into the evening that the ramp is closed by the time we are trying to leave? Will I be trapped in the city for the evening?

What if the show goes on so late into the evening? Why is the band I paid money to see and left the reasonable comfort of my home hitting the stage, like, three or four hours after the doors to the venue opened? How late past my bedtime will I be up?

There is the crowd itself—the other members of the audience. And one would, perhaps erroneously, think you would find yourself amongst people similar to yourself, at least with regards to taste in music, yes, but also regarding respect and courtesy for others. But this is, unfortunately, rarely the case and more often than not, you find yourself struggling to maintain any kind of personal space from someone who continues to bump into you.

This is, unfortunately, rarely the case when you are struggling to enjoy yourself when you are standing near someone who is talking during the entire performance.

And there were, as there often are, a couple of concerts announced at the end of 2019, slated for early 2020, that I was interested in—that passing interest and the brief flash of excitement when I see “Minneapolis” listed on a tour schedule. And I went so far as to labor over the idea of buying tickets—I considered, even with as horrible of a concert venue as it is, trying to get tickets to Thom Yorke at the Xcel Energy Center in St. Paul, the “other” Twin City; I considered smaller, exponentially more intimate shows at The Entry from extremely indie bands like Squirrel Flower and Longbeard.

I gave surprisingly serious consideration to buying a one-day pass to the Mission Creek Festival in Iowa City for the day that both Lucy Dacus was performing and Hanif Abdurraqib was giving a reading.

The pandemic begins.

And tours, of course, were optimistically rescheduled at first—sometimes two, or three times before the shows, and tours as a whole, were canceled completely. And despite any of my passing interest and fleeting moments of excitement, I never went through with buying tickets for any of those performances I was pondering. And as the state of the world, in the spring of 2020, began growing worse and worse, I felt a very small sense of relief from anything I had even considered trying to overcome my concert anxiety to attend being called off.

And even if the pandemic had not begun in March of 2020, and if these shows had actually taken place, and even if I had found a way to overcome any of my anxieties and bought tickets, there is a very good chance that I would not have had that great of a time anyway.

*

And it is something that I have not considered all that often in the last year or so, but recently—and especially recently, I have wondered if I would have been introduced to the music of Arooj Aftab if Pitchfork had not written about, and highly praised, her album Vulture Prince when it was released in the spring of 2021.

I have no idea what her career as a singer was like before that moment, but I have briefly wondered what her career would be like if it had not been given this, perhaps, unexpected boost through earning the honor of being named “Best New Music” from the site, along with scoring an 8.2 out of 10 from their extremely polarizing rating system.

I have briefly wondered if she still would have found her way to a much larger audience through Vulture Prince; if she still would have been nominated for two Grammy awards—winning “Best Global Music Performance,” but losing “Best New Artist” to Olivia Rodrigo.

Shortly after Pitchfork covered Vulture Prince, and shortly after a text from a college friend who suggested I take a listen to it, it became an album that I slowly immersed myself in—and, once immersed, it was an album I returned to almost daily for a while as a means to find a sense of comfort, or solace in, while listening, during what was an incredibly tumultuous time.

And this is to say that in 2021, Pitchfork is no longer the “tastemaker” it once saw itself as. It can help generate a buzz, yes, but it is not the only music website, or outlet, capable of really helping launch a somewhat unknown, or extremely niche, artist’s career to the next level.

Vulture Prince is an inherently beautiful record—it unfolds slowly and deliberately, never moving faster than it needs to, and in that inherent beauty, there is something extremely haunting. At least partially inspired by the passing of Aftab’s brother, Vulture Prince, a record sung almost entirely in Hindustani, can be intimidating, yes, because of the language barrier—but Aftab uses her voice, and the language she sings in, like an instrument, and as a meditation on grief, it transcends any kind of barrier in the otherworldly way it conveys melancholy.

And what I don’t remember now is how I even learned that Aftab had scheduled a tour—specifically a small tour of dates in the Midwest, but I felt, as I had often felt in the past, that brief flicker of excitement when I read she was going to be performing in Minneapolis at the Parkway Theatre, in April of 2022.

And I can’t say it was impulsive, exactly, but on a December evening, already believing that the show—at that point, five months away, would be postponed or canceled because of the pandemic, and already feeling extremely uncertain about my level of comfort, both at that moment, and how I might feel in the future (if there even was going to be “a future” at all by April of 2022) about being in a relatively small space with a large number of people at a time when that kind of an arrangement can be unsettling, I bought two tickets to see Arooj Aftab.

And much to my surprise, as 2021 became 2022, and as January became February and February became March and March became April and Aftab’s concert had not been postponed, or canceled because of the pandemic. And much to my surprise, even with the pandemic far from “over,” the number of confirmed positive cases began to drop so drastically that they, apparently, no longer need to be reported in daily statistical updates.

Much to my dismay, mandates on masking were being more or less lifted completely.

And much to my surprise, and in fighting against both my debilitating depression and my concerts anxieties—which had been dormant for over two years—I found myself, alongside my wife, in the first row of the Parkway Theatre on a Sunday night in April.

*

And it is at this point, when I sit down to write something, where we are closing in on, like, 3,000 words, that depending on how much of the story, or whatever, there is to tell, the different elements of that story begin to converge—it might not always make sense, though. Often I have been guilty of trying to connect too many very flimsy threads into something that, I, at least, think makes sense, but others who are reading it might see it as narratives being overextended.

My therapist and I—the one who loves Carly Rae Jepsen—have often discussed how the pandemic, and trying to operate in the world during the pandemic, has created a heightened sense of anxiety about my safety and comfort. During a somewhat recent session, perhaps in late February or early March, I mentioned to her I had tickets to a concert that had, somehow, not been postponed or canceled because of the pandemic, and that I was uncertain how I was feeling about going.

At the end of our Monday session, she quickly asked about the concert—she didn’t remember when it was, but knew it was coming up, and wanted to check in with me about “how I was feeling.”

The show, as it turns out, had been the previous night.

And surprisingly, I had felt okay—like, as okay as a person, like myself, can feel when they find themselves in a situation such as that during the times we currently find ourselves in.

Perhaps it helped that we were sitting in the front row—since I had bought the tickets five months in advance, I had completely forgotten where we were going to be seated. There were people behind us, yes, though I am extremely grateful the couple behind us who remained masked during the performance. It seemingly helped put me at ease that there was nobody in front of us—and it also helped that the Parkway Theatre is a seated venue, which, outside of providing literal comfort during the show (as opposed to standing for, like, 80 minutes) keeps people from inching any closer to you than they already are.

The Parkway Theatre—originally built in 1931 and renovated in 2018, holds less than 400 people. Two years ago, that might not have sounded like a lot of people, but today, to me, at least, that sounds like being in a room with around 375 too many. The venue itself, as most venues in the area have been doing, requires proof of vaccination upon entry, or proof of a negative test result 72 hours before the event. The Parkway, like most venues in the area have been doing, “encourage” people to keep their masks on when not eating or drinking, but it is no longer an enforceable requirement. Several folks were kind enough to keep their masks on upon entering the theatre, but since it is not a mandate, this means I saw a lot of faces.

And, perhaps, this is something you might still be getting used to as well, but after two years of seeing people’s eyes and little else, I am having a hard time reacclimatizing to seeing faces again. And there were a few times, before the house lights dimmed and the concert began, when I’d turn around and see the seats in the Parkway filling up—all of those people and all of those faces—and it felt familiar—a time, not all that long ago, when a room full of that many people, or more, was not a something that made me fear for my safety; it also felt extremely surreal and a little overwhelming to be, after two years, back in that kind of situation—given all of my own anxieties about “things opening back up” during a time when I still believe they, perhaps, still shouldn’t be.

*

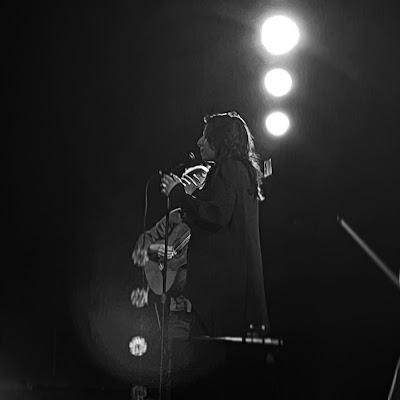

Following introductory remarks (at times, a little aggrandizing and promotional) from Kate Nordstrom, the artistic director of Liquid Music (one of the concert’s organizers and sponsors), and Philip Bither, the senior curator of performing arts at the Walker Art Center (the concert’s other organizer and sponsor), Arooj Aftab and her band made their way onto the stage shortly after the event’s expected 7 p.m. starting time.

And live performances can, of course, go many ways—they can be disastrous or incredible, and the songs themselves that the artist performs, can, of course, go many ways as well. A song can be played exactly how it sounds on the recording, or, it can have taken on new life, or grown in some way, and as the concert began, it was very apparent that the music from Vulture Prince, or, at least two of the songs that found their way into the Aftab’s set that night, have gone through surprising, and impressive growth since they were originally recorded—arriving on the other side of that growth dramatically reimagined and reconstructed.

It is difficult to describe Aftab’s sound—Vulture Prince is tagged on Pitchfork as “Jazz” and “Folk/Country,” and referring to the album as “World Music” would be diminutive and offensive. There is, of course, a “worldliness” to it—Aftab, born in Pakistan, sings primarily in Hindustani, but the music itself—like, how the instrumentation swirls and tumbles together dramatically, allowing her mournful, gorgeous voice room to float like a specter, is tough to articulate without sounding like you are attempting to recall something that came to you in a fever dream.

In his piece on Vulture Prince, Bhanuj Kappal writes about “the ghazal,” which he explains is the closest thing South Asia has to the blues because it is a form of music steeped in both loss and longing. And there are traditional elements to Aftab, and this collection of songs, for sure—ghazal, and Hindustani classical, but those are effortlessly merged with stark folk instrumentation, and the idea of “showing out versus showing off” that is almost synonymous with the proficiency and confidence of playing jazz.

Aftab’s set at the Parkway Theatre opened with the same song found at the beginning of Vulture Prince, the glistening, beautiful “Baghon Main.” The version that opens the record, though, is structured around the gentle, precise caresses of harp strings—an instrument that, at least for her performance in Minneapolis, was noticeably missing from the stage. “Baghon Main,” one of Vulture Prince’s most devastating, gorgeous, and sweeping moments, is one of the songs that, in a live setting, has taken on a new life.

Beginning with an extended acoustic, classical guitar solo from Gyan Riley, the song eventually found its slow, slinking rhythm as Shahzad Ismaily’s subdued, strong bass playing cascaded in and out through his control of a volume pedal, and the theatrical, haunting violin playing from virtuoso Darian Donovan Thomas wove their way into the texture of the song.

By no means less gorgeous, or breathtaking live than it is on the LP, there was something a lot more raw, or unpolished, as the notes floated from the stage and into the audience at the Parkway—a feeling, perhaps, created by the fact that the song was not “stripped down” exactly, or any more sparse or skeletal in its arrangement, but Riley’s acoustic guitar, tackling the progression that usually would be heard from the harp, made the song a little less shimmery and little more unpredictable—but no less devastating, poignant, and alluring to hear.

Much more noticeable than the extended introduction and slight adjustments made to “Baghon Main,” was the brooding, hypnotic deconstruction to “Last Night”—the only tune on Vulture Prince featuring Aftab singing in English.

The album version of “Last Night” is the most sultry, and slithering on the record, built around a dub-style rhythm, it is also the only song on the album to include noticeable percussive elements. And within the context of the album, I hesitate to describe “Last Night as a “low point” on the record, but its jaunty nature creates a rather startling shift in tone as Vulture Prince hits its halfway point.

The life “Last Night” has taken on though, now, is anything but jaunty.

Doing away with literally every lyric in the song except the repetition of the titular phrase—“Last night, my beloved was like the moon—so beautiful,” the band transformed the song into something surprisingly dark and ominous—bathed in red stage lights, Aftab, as she often did while performing, became visibly lost in the moment being created, while her band conjured up an inverse, if you will, to the song’s arranging by building something pulsating that, as it slowly crept off the stage, through the audience, became truly unsettlingly, extremely tense, and undeniably compelling.

*

There was a time, near the end of 2018, when I found myself attending around three concerts in relatively short succession of one another, which some might say was uncharacteristic of myself. One of those was Kamasi Washington at the Palace Theatre in St. Paul. Washington, out on the road behind his sophomore release, the 5 x LP Heaven and Earth, made it through, like, six songs I think during his 90 minutes on stage.

Six songs, on paper, appears to be a relatively short set.

Six songs, in execution—especially in execution by a jazz band, is anything but.

And you would be able to say the same thing about Arooj Aftab’s set in Minneapolis. Aftab and her band performed seven songs, which doesn’t seem like all that many, at first, but those seven songs slowly unfurled themselves across, like, 80 minutes.

In the promotional materials for Aftab’s performance at the Parkway, and on the venue’s marquee the evening, the show was touted as “Arooj Aftab - Vulture Prince,” and the implication there was that she would, more than likely, be performing the album in its entirety.

Missing from the live show was the swirling, sweeping “Inavaat,” and it makes sense that this song was not performed, simply because it is constructed around the piano (an instrument not on stage at the Parkway) and, again, the harp. However, Aftab and her group did perform a lengthy arrangement of the skittering “Suroor,” which is technically Vulture Prince’s final track, though it is strangely omitted from the album’s original vinyl pressing.

The group also performed a “new” song—“Udhero Na,” which was recently released in conjunction with the announcement that Aftab had signed with Verve Records—an iconic jazz label and a subsidiary of Universal Music, and that Verve would be reissuing Vulture Prince in June on CD, as well as an expanded double LP.

Speaking about the reissue was one of a handful of things Aftab shared with the audience in between songs—her experience at the Grammy Awards was another. Speaking somewhat delicately because she admitted to more or less destroying her voice from screaming so much during the award ceremony, Aftab also confessed to the audience she had not consumed any alcohol before the performance that evening, and that usually, she was pretty “wasted” by the time she was on stage.

“We drank so fucking much yesterday in Iowa City,” she exclaimed, in reference to the band’s appearance at the Mission Creek Festival.

A little over a year ago, while reading Hanif Abdurraqib’s A Little Devil in America, I was introduced to the idea of “showing off versus showing out.” The notion of it runs throughout the book, but it is explained in the book’s first essay about the show “Soul Train,” specifically the Soul Train Line. “I consider, often, the difference between showing off and showing out,” he writes. “How showing off is something you do for the world at large, and showing out is something you do strictly for your people. The people who might not need to be reminded of how good you are but will take the reminder when they can.”

Arooj Aftab and her band, throughout their set at the Parkway, walked the line between both showing off and showing out—showing off for the audience, of course, with band members Thomas and Riley, specifically, taking the time to demonstrate the precision and skill they have with their respective instruments; and showing out for each other, and for themselves—the jazz adjacent soloing and possible grandstanding isn’t always necessary, but it does create the juxtaposition of how each instrument, and performer, is important to the whole while still being able to stand on their own when given the opportunity.

The group had deconstructed or reimagined two of the set’s seven songs, the rest of the songs were not all that dramatically different from their original iterations. My favorite piece from Vulture Prince—perhaps the most somber of the entire album, “Saans Lo,” was still just as emotionally stirring, even though Riley performed the song’s icy and slow guitar string plucking through his nylon string acoustic (run through myriad effects pedals) as opposed to the electric guitar used on the album version.

Aftab, as a vocalist and, perhaps, the defacto “bandleader,” creates an environment that encourages room for improvised experimentation—more than likely in the name of showing off, or showing out. Within that room for experimentation though, sometimes things did not exactly work, or land as intended. Thomas, when not playing the violin, could be found hunched over his pedalboard, and within his effects fuckery, pushed his violin into a field of 8-bit, chip tuned distortion that, while providing a moment of whimsy, was also a little distracting and grating.

*

During my lifetime of attending concerts, I have been introduced to, or at least had the opportunity to enjoy, bands I might have not otherwise discovered through their appearance as the opening, or “supporting” act—The Frames, opening for Damien Rice in 2004; Land of Talk opening for Broken Social Scene in 2008; a solo Annie Clark performing as St. Vincent before The National in 2007.

In contrast, I have had the displeasure of standing politely through some absolutely forgettable, or downright awful, supporting acts as well.

It is, perhaps, rare for the headliner, or main act, to perform without another group offering a shorter, supporting set, but I was extremely grateful that Arooj Aftab and her band were the only act on the bill at the Parkway. The show started relatively on time, and without another band playing for a half-hour or 45 minutes, then time for the stage changeover, it made for a surprisingly early evening—and on a Sunday night, and for someone who is pushing 40 (as I am), I was thankful that we were departing the theatre by, like, 8:45 p.m.

The final song of Aftab’s set was the seductive, dizzying “Mohabbat,” and she introduced it by saying she had saved “the banger” for last, and after the song, much to the surprise (and perhaps dismay) of the audience, the band did not perform an encore.

Something that I, too, was thankful for.

And that is to say I was not enjoying myself, or that Aftab and the band were not deserving of returning to the stage for another song, but I find the idea of “the encore,” specifically at a contemporary popular music concert, to be a bit performative—going through the motions of announcing a song as your last in the set, saying goodnight, then keeping the audience in a sense of anticipation, and eventually making a big show of sauntering back onto the stage to a rupture of applause, and announcing you’ve got “a few more” songs to play.

Because for someone who is pushing 40 (as I am), and has a 45-minute drive ahead of them, I was thankful that we were departing the theatre by, like, 8:45 p.m.

*

There is a deliberately slow catharsis to Arooj Aftab’s music. The simmering, albeit subtle, tension and then ultimate release.

But in that catharsis, both on stage, and on the album, is there resolve?

There is a worldliness to Arooj Aftab because of the culture and heritage she brings to the music she’s making, but more important than that is the otherworldliness created on the record, and the stage. Vulture Prince, as an album, was something I used as a means to find comfort and solace during an extremely difficult time, and it was music I could easily get lost in.

In the communal aspect of watching Aftab perform live, Vulture Prince was less about solace, but is still incredibly easy, and perhaps it is expected to get lost in, and transfixed in, the way she and her band recreate the songs on the stage. I watched, and listened, with absolute awe, often holding my breath simply because the atmosphere being created was just so devastatingly gorgeous and inspiring, that I was afraid, or unable, to exhale.

In the catharsis, is there resolve?

I am told there is a space where both grief and joy can coexist, though I have, as of yet, been able to find it for myself, and the grief that I have carried with me for so many years. Vulture Prince, a meditation on grief, is far from joyous, but it, both as an album and as a live experience, blurs the line between mourning and celebration, creating a revelatory statement of beauty.