The Palest Blue - Nick Drake's Pink Moon at 50

Nick Drake and I are both tall—not “freakishly”1 tall, or professional basketball player tall, but tall enough that it becomes, however minor, a defining characteristic.

Drake stood 6’3.” And his mother, Molly, was quoted as saying that, the day she opened her son’s bedroom door, discovering his lifeless body, the first thing she saw, on his bed, were his long legs.

I am 6’2.”

Near the end of 2015—which, retrospectively, I can accurately says tracks with where I was emotionally, or mentally, during this period of time—I felt compelled to download all three of the albums Drake released in his lifetime: his 1969 debut, Five Leaves Left, its follow up from 1970, Bryter Layter, and his last studio album, 1972’s Pink Moon.

There are no instrumentals on Five Leaves Left; on Bryter Layter, there are three—two of them bookending the album, with the other arriving at the halfway mark; on Pink Moon, there is one. Arriving near the album’s halfway point, barely over a minute in length, the eerie, chilling “Horn,” so short that it almost gets to its ending as soon as it begins—the low strings on Drake’s open tuned acoustic guitar resonating, while the higher strings cut through with an icy glisten.

It’s a fragment—a sketch that is quick, yes, but also complete enough to be referred to as completed. Or as completed as he wanted it to be.

A fragment—maybe a bit of a stretch, but an allegory for Drake’s life and fleeting career in the early 1970s.

I don’t remember how we came to feel this way, but shortly after I had downloaded Bryter Layter, as well as Drake’s other two full-lengths, and put them onto the second-hand iPod I purchased for use in the car, my wife and I had determined the instrumental piece that opens Bryter, aptly titled “Introduction,” had some kind of soothing effect for her—especially if we were traveling somewhere in the car. It became a bit of an in-joke in the house, but for all of 90 seconds, Drake’s acoustic guitar is punctuated with a lush string arrangement and gentle percussive elements rolling through underneath it all.

It is the kind of piece that you wish could go on for a lot longer than 90 seconds before it reaches its peak and ends—ushering in the myriad musical aesthetics Drake would attempt adopting into his songwriting as the album unfolds; the record concludes with “Sunday,” a much longer instrumental primarily based around the flute and the strings that accompany it—Drake’s guitar playing on the song is so subdued I would say it’s not even secondary to the other instrumentation within the song.

There are moments when “Sunday” hits a bit of a whimsical, or a jazzy stride—these kind of descriptors are very akin to the arranging of various songs on the record—and there is something…it isn’t dissonance, but something very uneasy, or tense, about the way the flute sounds throughout “Sunday,” especially as it opens. It isn’t sinister, and I hesitate to say it sounds menacing, but it is ominous.

A long shadow, growing darker.

Nick Drake and I are both tall—not “freakishly” tall, or professional basketball player tall, but tall enough that it becomes, however minor, a defining characteristic.

Casting long shadows.

Growing darker.

*

Nick Drake’s recorded output is, of course, strong enough to stand on its own accord, but it is also always at risk of buckling under the weight of its own, complicated mythology—specifically, Pink Moon, an album that could be viewed, and more than likely is viewed by many, as a defining final statement before he retreated even further inward and the long, slow, depressive decline that lead to his death in 1974.

He was 26.

Drake’s story—brief, complex, harrowing, has been told and retold a number of times—in 1997, two years before his unprecedented posthumous surge in popularity, Patrick Humphries published a biography on Drake; roughly a decade later, Trevor Dann wrote Darker Than The Deepest Sea: The Search for Nick Drake.

The first reader review of Dann’s book, on the site Goodreads, begins—“Well, you didn’t find him.”

In 2007, Pitchfork writer and current contributor to The New Yorker Amanda Petrusich wrote about Pink Moon for the Bloomsbury Group’s 33 1/3 series, and before her narrative becomes completely weighed down in the argument of artistic ethics and use of the album’s titular track in a now infamous Volkswagen commercial from late 1999, she does a good job of succinctly piecing together Drake’s life and career.

Originally dismissed by Island Records following his own attempt at submitting demo recordings he made while still a college student, it was after he inked a (questionably written) management, publishing, and production contract with Joe Boyd’s Witchseasons Productions that finally got him in the door of the label—then entering into difficult sessions to record his debut, the lush and pastoral Five Leaves Left, released in 1969 to little, if any, notice. Bryter Layter—exponentially less pastoral and “folky,” still a robust sounding collection, it however leans heavily at times in to a jazzy, pop oriented sound, and it was met with a similar commercial and critical fate.

Shortly after its release in 1970, Boyd sold his production company to Island, moving to Los Angeles for a job at Warner Brothers Records.

Already spiraling deeper into mental illness, prescription medication he purposefully neglected to take, and purported substance abuse—hallucinogens, “copious” amounts of pot, and possible dabbling in heroin, introduced to him from Velvet Underground’s John Cale, an increasingly insular Drake entered a recording studio in the fall of 1971 with producer John Wood, who had engineered the Bryter Layter sessions.

Recorded over two nights, with no other musicians or any other studio personnel present, the thing that struck me this time about Pink Moon, both listening analytically for the first time, but also having just read Petrusich’s book on the album, is that, save for the short (and now iconic) piano accompaniment that arrives within an instrumental break during the titular track, there are no overdubs, and no additional instruments on the record.

It’s just Drake, alone, with his guitar.

I really hadn’t put it together like that before.

*

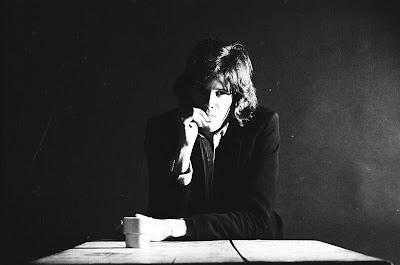

He had appeared on the covers of Five Leaves Left and Bryter Layter, but attempts at photographing Drake for the Pink Moon sleeve were abandoned when photographer Keith Morris saw just how despondent and disheveled Drake had grown.

The urban legend—contributing to the mythology around Pink Moon, and it turns out this isn’t true, was that Drake left the master tapes to Pink Moon at the front desk of Island Records without saying a word.

In March, 1972, Pink Moon was released and like its predecessors, it was met with little if any attention from critics and audiences. The label’s A&R was disappointed and frustrated at Drake’s more or less refusal to promote the album in any way—the handful of times he did perform live in the past, he was nervous and increasingly uncomfortable, with the performances allegedly becoming awkward disasters.

It isn’t mentioned in the 33 1/3 book about Pink Moon, but Drake was apparently hospitalized for a number of weeks following a nervous breakdown at the beginning of 1972, and was beginning to show symptoms of schizophrenia. Following the release of the album, and the disappointment with its lack of popularity, Drake resigned to move back into his parent’s home—a documented difficult existence that, like the urban legend of his quiet submission of the Pink Moon masters, contributes to the growing mystique and mythology around Drake as a troubled artist.

He would apparently leave the house and be missing for days, turning up unannounced at the houses of friends; and, perhaps, the first story I heard about Nick Drake, in college, from my friend Kat, who had been a longtime fan—that Drake would often aimlessly drive, eventually running out of gas, then calling his parents, asking them to come pick him up.

Even with his metal health continuing to deteriorate, withdrawing further into himself, in 1973, Drake reached out to John Wood, inquiring about recording a fourth album—there were two sessions, the second being in the summer of 1974. During those final sessions, Drake’s health was so poor he was unable to both sing and play the guitar at the same time, requiring Wood to overdub the tracks.

It was also then, Wood noted, how embittered Drake had grown from his lack of success.

*

Near the end of 1999, “Pink Moon” was licensed for Volkswagen commercial, soundtracking four attractive young people tooling around in the company’s Cabrio convertible—the spot, titled “Milky Way,” was originally introduced through an email to recipients on VW’s mailing list—the message also included a link to order Pink Moon on CD from Amazon—long squandering in obscurity, and very slowly developing a cult following throughout the rest of the 1970s and into the 1980s, the usage of “Pink Moon” in the commercial brought the album’s sales to 74,000 copies by the end of the year 2000.

I would have been 16 years old when the Volkswagen commercial began airing on channels I regularly watched, like MTV and VH-1, and I have very faint memories of seeing it, and hearing the song. What I cannot remember is if I was moved at all by the portions of the song that had been featured in the ad—and in a time long before apps like Shazam, if I had wondered who was responsible for the tune.

Later, I can recall seeing a CD copy of Pink Moon in a record store—a Musicland, more than likely, with a small, circular hype sticker adhered to the cellophane it was wrapped in, reading “As Heard in the V.W. Ad.”

Drake’s Bryter Layter track “Fly” had been included in the film The Royal Tennenbaums in late 2001, but I didn’t start listening to Nick Drake until I was a junior in college—and even then, I am uncertain if I could call this really listening. Actively listening.

Thoughtfully listening.

In the late autumn of 2003, I was in a production of the play Off The Map2—and the director, Joe, one of my professors, was selecting music cues to be used throughout the production between the beginning of each act, as well as incidental, transitional music between specific scenes.

Among the music he selected was Nick Drake—so much time has passed now and I am unable to remember all the songs, by Drake, or otherwise, he chose to use within the show, but there are two that I can recall specifically—they way they echoed out through the cavernous theatre building on campus, and the way the stage lights dimmed once the notes of Drake’s acoustic guitar reverberated out of the speakers hoisted up on wooden stands and placed on either side of the stage, behind long, flowing, dusty black curtains.

One of the songs we used was “Black Eyed Dog,” a song Drake had recorded during his ill fated final sessions in 1973 or 1974—thought to be “destroyed” after his passing, it would later turn up on a collection of ephemeral material included in the Fruit Tree boxed set.

The other was the eerie, dissonant, creeping instrumental from Pink Moon, “Horn.”

Joe and I, outside of rehearsal or a classroom setting, often talked about music, and I had borrowed his stack of Nick Drake CDs, but rather than making copies of each album, and listening to these records the way Drake had intended, I made a sprawling Nick Drake mix on a CD-R, attempting to fill up the 80 minutes of available space on the disc.

I can recall opening the mix with the hypnotic “Cello Song” from Five Leaves Left, and I know that some of less ostentatious tunes from Bryter Layter ended up on the mix as well, like “Hazy Jane II,” “Chime of The City Clock,” and “Northern Sky.”

When I do not recall, outside of “Place to Be,” and the title track, how much of Pink Moon I had opted to include.

The CD-R is long gone now.

And what I did not understand, or appreciate when I was all of 20 years old, but have I have come to have a better understanding of and appreciation for now that I am on the cusp of 40, is that Nick Drake was a difficult, troubled artist, and Pink Moon is a difficult, troubling album.

And that’s the point of it.

Was it a “cry for help” recorded two years before his still debated overdose on prescription antidepressants? In sitting down to both analytically listen to Pink Moon, and also to write about it with as much reflection and clarity as I am able to now, I read a quote that said something about how, at the time of its recording, Drake had receded so far into himself and his mental health issues, it is tough to know “what these songs are about.”

And maybe that’s the point, or, at least, was part of the intent of the album—shrouded in just enough poetic ambiguity they can be taken a number of ways, something that contributes to the mythology of the album, and Drake’s enigmatic persona.

Arguably, Pink Moon is a product of depression, though members of Drake’s family will contest that Drake was unable to write when he was extremely depressed—so if anything, after 50 years, it could be looked at as a reflection on mental illness and an understanding of his own mortality, exhaled out during a fleeting gasp for air, before being submerged again.

Before drowning completely.

*

I would never say that Pink Moon, as an album—just an album, and trying my hardest to remove it from the mythology around it and the person who made it, is a type of inaccessible listen, but it also is not exactly the kind of record that lends itself to a casual, or passing listen the way Drake’s other albums might. And for an artist who, in the end, was frustrated by the lack of fame he had achieved, it is interesting to think about that facet of Drake’s personality, then the undeniable tone of his final album.

It is as if he was almost betting it all on the listener—putting too much faith that hordes of people would “get it,” regardless of how dark his music had become in a short amount of time. It’s admirable, to an extent, to gamble that hard—it’s something artist still do today, and when it does pay off, or work, I am sometimes astonished there are enough thoughtful listeners out there who have that kind of patience, when there are so many others who are unwilling to work that hard, or put in that much effort.

A large portion of Petrusich’s book regarding Pink Moon is dedicated to quotes, or contributions, from other musicians—Duncan Sheik, Lou Barlow, Christopher O’Riley, and Damien Jurado to name a few. And in these sections—where others talk (often briefly) about their own experiences with Drake and Pink Moon, many of state a version of the same thing—as much they love the album, or the impact it has had on them, they do not often return to it regularly, which is something I can both understand, and not understand, at the same time.

Difficult is too strong of a word but it is a challenging record and for even as well-loved as its titular track is, and can be extracted from the context of the album as a whole, it is an album that, at less than a half hour in length, is best listened to from beginning to end, without interruption.

And perhaps, if I may break the fourth wall here between you, the reader, and myself—breaking the wall more than I maybe already have, but I am wondering if, in even the short amount of analytical listening I have done with Pink Moon, I have reached the point where, and maybe this is a bit of a reach, or stretch, but I have started feel like there are slight differences in tone and performance across the album—elements or details you can hear in a handful of tunes that you do not hear in others, and I have to wonder about, across the two night sessions for Pink Moon, which songs were recorded on which night—and if Drake found himself feeling slightly better (or, slightly worse, as it were) one night more than the other.

And if you can feel that, or hear it, in the textures of the album.

Maybe this feeling that I am getting from the record now, really listening to it, is just another layer of mythology for an album, and an artist, who doesn’t need, at this point, any more of that.

Something that I had not considered, and it makes sense given how, by the time he entered the studio in 1973, his faculties were failing him, is the quality of his voice on Pink Moon. Petrusich touches on it in the little bit she does discuss the album itself in her 33 1/3 volume—but there, between the way Drake sounds on, say, Bryter Layter, and the small, but noticeable, changes in Pink Moon.

The example given was the way he more or less mumbles the lyrics to “Pink Moon,” or, at least, slurs the diction—he does this elsewhere on the record too. Something that doesn’t make the lyrics, or his singing, seem secondary to the guitar playing, but there is a carelessness or distance created by it, whether intentional or not, that gives the impression of someone so focused on one thing (his dexterous guitar playing) that the other thing is slightly less important. It is, however, well documented that within his final years—even while trying to record Pink Moon, Drake was unable to speak, or at the very least, articulate himself well enough to be understood.

Pink Moon as an album is a slow burn—and it begins to gain more momentum, or hit more of a stride, by third track, “Road,” one where Drake’s voice seems a little stronger, the way it natural files itself in the spaces created by the dizzying, practically hypnotic way his fingers dance across the strings of his guitar—and, I mean, that is the way you could describe his intricate guitar work throughout Pink Moon; even when the songs don’t exactly work (for me, anyway), like the bouncing riff that he uses through the entirety of “Know,” or from the album’s second half, “Free Ride,” and “Harvest Breed. He has a way of not so much commanding the instrument, but works with it, showing patience and dedication to it—and it can be astonishing, still, to this day, to hear that kind of meticulous, yet fragile, quality in his playing.

In contrast, Drake’s voice is not as strong, or at least not as clear, on the folksy, very rootsy “Which Will.” He can still hold the notes, though, mostly aware of his own limitations in the range he has across the album, but here, he falls back into a kind of mumbling, less clear delivery that, even now that I have noticed this trend on Pink Moon, still works, and is still fine—and here, it lends itself well to the kind of loose, swaying nature of the song’s rhythm.

And perhaps the ominous tone is introduced, at least a little, early on in Pink Moon, but Drake returns to it, slowly at first on “Things Behind The Sun,” which closes the album’s first side, and the album’s most dramatic, or sweeping track, “Parasite,” sequenced early in the second side, both of which, the further I listened, I felt could have, with some effort, been arranged for additional instrumentation, and could have found their way onto his previous albums, but the way they are presented here, stark and a little ragged, is equally as impactful.

There is no big finale on Pink Moon, which I suppose makes a lot of sense with the overall aesthetic of the record, but also with where Drake was mentally at the time of its recording and delivery to Island Records—even when his songs were more developed through additional instrumentation, his mythology dictates there was an unassuming nature about him, and Pink Moon ends with the unassuming, “From The Morning.”

Bryter Layter is bookended by instrumentals, and even Five Leaves Left is flanked by perhaps its most aloof or “freewheeling” tunes—here, though, I still am uncertain if there is a slight connectivity between “Pink Moon” and “From The Morning.” The contrast of night and day is apparent from the titles alone, but there is little else joining them, or allowing them to be reflections of one another. While “Pink Moon” is as much of a thesis statement for the album as you’re going to get, “From The Morning” is one of the songs on the record where Drake’s playing as a sense of desperate urgency to it—sounding at times like he is almost getting ahead of himself slightly, or caught up in his own dexterity and precision, which is kind of how it sounds as the song comes to an unassuming end.

It quickly moving pattern of string plucks begins to slow, then fumble, then it somewhat abruptly ends.

Another reach, on my part, but the abrupt ending—another allegory for Drake’s life.

*

Maybe not as much as I did when I was in my late 20s and early 30s, but I still find I am drawn to the art created by troubled artists—predominately troubled artists who happen to be white men.

David Foster Wallace, author of Infinite Jest, and a number of sprawling, brainy essays, among other things, was a well documented misogynist early in his literary fame; grappling both mental health issues along with substance use, it is also now a well known fact that he was both physically and psychologically abusive toward fellow writer Mary Karr during a brief, volatile relationship they had.

Wallace died by suicide in 2008. It is difficult to defend or reconcile many of his behaviors—it was also difficult, as conflicted as I am about Wallace now, to read through the graphic depiction of his 10 month decline—leading up to the end, as detailed in the 2012 biography Every Love Story is A Ghost Story.

Jason Molina—the singer and songwriter behind the late 90s and early 2000s indie folk outfits Songs: Ohia and The Magnolia Electric Company died in March of 2013, his body, both inside and out, ravaged by a decade of unprecedented alcoholism. His descent, numerous failed attempts at sobriety, and the crumbling of his professional and personal relationships—including estrangement from his wife—is harrowingly told in the 2017 book Riding With The Ghost.

Reading about the slow, brutal downward spiral, and inescapable end of an artist whose work you admire is extremely challenging.

Writing about it, as you might imagine, isn’t any easier.

When interviewed for Trevor Dann’s biography on Drake, Muff Winwood, the head of A&R at Island records during the 1970s is quoted as saying, “We saw it coming. We shrugged our shoulders and thought, well, that wasn’t unexpected.”

The story goes that on the morning of Sunday, November 24th, 1974, Nick Drake hobbled from his bedroom in his parents’ house, down to the kitchen, where he ate bowl of Corn Flakes. He then went back to his room, got into bed, and ingested the entire bottle (30 doses) of the prescription antidepressant Tryptizol (Amitriptyline.)

He left no note, save for a letter addressed to his friend Sophia Ryde. Biographers refer to her as the closest thing Drake had to a girlfriend (there is speculation Drake was on the asexual spectrum) but Ryde was remiss at that description, instead calling her his “best (girl) friend.” Whatever their relationship, however intimate they were—platonic or otherwise, Drake’s worsening mental state took eventually its toll on his dynamic Ryde—a week before Drake’s death, she had asked him “for some time.”

“I couldn’t cope with it,” she is quoted as saying. “I never saw him again.”

There is speculation that, within entendre in the title, the Pink Moon song “Free Ride” was written about her.

Drake’s former producer and manager, Joe Boyd, believed Drake’s death to be an accident. He is quoted as saying he imagined Drake ingested such high dosage of antidepressants in a last ditch effort to recapture a sense of optimism—“a desperate lunge for life rather than some calculated surrender to death.”

Around the time of his death, there had been reported moments where Drake seemed in higher spirits and even expressed interest in trying to revive his career—the second of his most recent recording sessions with Pink Moon’s producer had been a few months prior. However, his retainer from Island Records had ended, and it is presumed his slightly better mindset ended and he “crashed back into despair.”

Ruled a suicide by the coroner in December, 1974, Drake’s death is not “contentious,” but it is something that was, and still is, debated. Those close to him at that time admit he had “given up on life,” but his father, Rodney, was quoted as saying that his son’s passing was unexpected. Both of Drake’s parents though, admit they were often worried about him, and the state of his deterioration—going so far as to hide aspirin and other pills.

Drake’s sister Gabrielle’s sentiments are among the most sobering, and perhaps the most realistic—“I’d rather he died because he wanted to end it rather than the result of a tragic mistake,” she said. “That would seem to me to be terrible—for it to be a plea for help that nobody hears.”

A plea for help that nobody hears.

We shrugged our shoulders and thought, well, that wasn’t unexpected.

*

If you listen to Pink Moon in sequential order, “Pink Moon” and “Place to Be” open the album’s first side, and at first—like, within the first strum or two of Drake’s guitar, they sound eerily similar.

Or, at the very least, there is a similar feeling that comes from when his fingers grace the strings in that first second or two of each song before they go their separate ways.

What is a song like “Pink Moon” about?

There is a habit of searching for clues, or answers—subtle or otherwise, in the art produced by an artist that has passed away, especially if that artist has died by suicide, or, if lingering questions about their death remain.

When he aloofly wandered into the Wolf River, a tributary of the Mississippi River, for a quick swim, Jeff Buckley’s bandmates expected he would return—and that he wouldn’t have been swept away in the unpredictable current, found dead roughly a week after he was declared missing. It becomes easy to comb through his lyrics—certainly not as troubled as he was mercurial, searching for hints or suggestions that he was acutely aware of his own mortality.

In the wake of “Pink Moon’s appearance in the V.W. commercial in late 1999, I remember the topic of its very usage was discussed on some kind of “talking head” based program on VH-1—one of the folks being interviewed, and I don’t recall which publication she wrote for, or worked for, but she seemed simply abhorrent to the notion that Drake’s song had been licensed for the advertisement because it was about “prophesying his own death.”

What is a song like “Pink Moon” about?

Saw it written, and I saw it say—pink moon is on its way

There are songs on Pink Moon that have more to them, in terms of their lyrics—more lyrics, to begin with; like, more words on the page, or whatever, but also more to unpack. And for as infamous as it now is, there is very little, actually, in the song “Pink Moon.” The song itself runs barely over two minutes in length—it is one verse that is repeated, and the simple, observations chorus of, “It’s a pink moon.”

It’s more about the feeling—the feeling within the song, that Drake, perhaps, inadvertently created, and the feeling that it evokes from the listener.

And none of you stand so tall—pink moon gonna get ye all

There is something terribly ominous about that line, isn’t there? Ominous and accusatory—“None of you stand so tall,” he mumbles. “Pink moon gonna get ye all.”

The internet, of course, is full of ideas on what the song could be about—a description of the color the moon turns during an eclipse, or a reference to some kind of “end of days” reckoning.

Or, like the “talking head” critic from a VH-1 show however many years ago suggested—it’s about Drake being grimly aware of his own mortality.

For as dark as “Pink Moon” is, lyrically, or at least dark in an abstracted kind of way, musically it is very breezy—he never really relents with the acoustic guitar strumming, and that piano accompaniment that joins in shortly after the first minute of the song, lasting all of, like, 20 seconds total, adds a sense of lightness. It’s beautiful, and probably makes the song what it is if you think about it—the way the keys are very deliberately hit, each note precisely tumbling into the bed that muddy, hollow sound of Drake’s acoustic guitar has made.

It is difficult, now, 50 years removed, to even know where to begin with an attempt to analyze what some of the songs on Pink Moon are “about.” And I have to wonder if it’s really all that important—there’s a sneering resentment that runs through “Free Ride,” and the unnerving and the presumed self-loathing that boils to the surface of “Parasite”; if there is any moment on the album that can be unpacked with ease, it’s the album’s second track, “Place to Be.”

A plea for help that nobody hears.

There is a dichotomy that runs throughout the three verses of “Place to Be,” and not that Drake was ever one to adhere to a traditional song structure, but it, like a number of the songs on Pink Moon, features no chorus—just verses that detail, through slight poetic ambiguity, Drake’s contrasting mental states along with a very palpable longing.

For someone who was 23 or 24 when he wrote “Place to Be,” it is surprising, maybe, that he opens the song with a reflection on feeling “older.” “When I was young, younger than before,” he sings in the first verse. “I never saw the truth hanging from the door. Now I’m older—see it face to face. And now I’m older, gotta get up, clean the place.”

I don’t listen to a lot of music from this time period—or even prior to the early 1970s. I was not raised, like many in my generation, by parents that played The Beatles. I have an appreciation for the R&B and soul coming from artists on Motown in the 1960s, and outside of a tattered copy of The Rolling Stones’ Hot Rocks that I bought in high school, I do not spend a lot of time regularly listening to contemporary popular music from the past.

Certainly, at some point after I was introduced to Drake’s work when I was in college, the sentiment of “Place to Be” resonated with me, though now, analytically looking at Pink Moon as a whole, as well as Drake’s short career, what is surprising about this song, specifically, is just how seen I feel by it—something I expect to happen with more recent pop music, not something I was anticipating with a song from 1972.

“I was greener greener than the hill,” he continues. “Where the flowers grew and the sun shone still. Now I’m darker than the deepest see—just hand me down, give me a place to be.” “Place to Be”’s third verse continues Drake’s use of contrast, but it also becomes more apparent that there is a very real hopelessness written into the song within those juxtapositions. “I was strong, strong in the sun. I thought I’d see when day was done. Now I’m weaker than the palest blue—oh so weak in this need for you.”

That admission of hopelessness—it passes by so quickly in the speed of the song, but it creates one of the very human, very real moments on Pink Moon. A clear portrait of someone fragile, seemingly aware that they were so close to breaking.

*

I had never heard depression described this way before until around a year ago, in the Arlo Parks song, “Black Dog,” where she details, with rather devastating accuracy, what it is like trying to stand by, and help a friend through a depressive episode.

The most difficult lyrics in the song come early on—“Sometimes it seems like you won’t survive this; and honestly, it’s terrifying.”

And I do not know if it’s a primarily an English expression, but the description, “Black Dog,” seemingly originates, or at the very least, can be traced back as a colloquialism from Winston Churchill—how he would describe living with manic-depression. The first article that comes up when you search “Winston Churchill Black Dog,” from a website called The Conversation, claims Churchill would be so paralyzed by despair that he “spent time in bed and had little energy, few interests, lost his appetite, couldn’t concentrate. He was minimally functional…,” and that these periods of time would last a few months before he would eventually find his way out of them.

During his recording session in the summer of 1974, Nick Drake recorded a song called “Black Eyed Dog,” and the guitar work is so precise and intricate—plucked out with a sonic quality on the instrument that is absent from how his guitar playing sounded on Pink Moon, it is heartbreaking to know Drake was in such a state during these sessions where he was unable to both play and sing at the same time, and that his vocals—fragile, a little warbled, were overdubbed.

There is the slight possibility that the titular black eyed dog in Drake’s song is a reference to something else—I am uncertain where I read this in the time that I have spent reading about Drake, and the myriad internet tabs I’ve had open, but this could be some kind of religious, or at least, Biblical imagery—similar to the allusion to an end of days one could take from “Pink Moon.”

But more than likely, “Black Eyed Dog” is Drake trying to come face to face with his depression—not trying to beat it, or work through it, but an exhausted acceptance.

“Black eyed dog, he called at my door,” Drake begins in the song’s opening line, his voice in a higher register, so delicate it sounds like it might shatter. “The black eyed dog, he called for more. The black eyed dog, he knew my name.”

The second verse—if you can even call it a verse, rather than more of Drake’s meditative ruminations, is even more difficult and haunting to hear: “I’m growing old, and I wanna go home. I’m growing old, and I don’t wanna know.”

She wrote it in the spring of 2019, and I will never tell anybody what combination of words I used to search for it online, but near the end of 2020, I found an essay by writer Anna Borges, entitled “I am Not Always Attached to The Idea of Being Alive.”

The essay is about her own passive, chronic suicidal ideation, and the way she describes living with it is like “living in the ocean.”

“Not as sea creatures do, native and equipped with feathery gills to dissolve oxygen for my bloodstream, but aloe, with an expanse of water at all sides. Some days are unremarkable,” Borges writes. “Floating under clear skies and smooth waters; other days are tumultuous storms you don’t know if you’ll survive.

“But you're always in the ocean. And when you live in the ocean, treading to stay afloat, you eventually get the feeling that one day, inevitably, there will be nowhere for you to go but down.”

Nick Drake and I are both tall— tall enough that it becomes, however minor, a defining characteristic. Drake was 6’3.” I am 6’2.” And reading about the slow, brutal downward spiral, and inescapable end of an artist whose work you admire is extremely challenging.

Writing about it, as you might imagine, isn’t any easier.

Nick Drake and I are both severely depressed.

Something I hadn’t understood, or really acknowledged until it was pointed out to me a number of years ago, is just how insular depression makes you—bordering on being extremely selfish, emotionally, albeit unintentional. And even if, after something like that is brought to your attention, and even if you are trying not to push the people closest to you away, or alienate them somehow, it is an illness that cannot help but damage, or in some cases, completely destroy your relationships with others.

On a good day, I can be difficult; on a bad day, I can be impossible.

So when I read about the depiction of Drake’s descent into depression—his inability or eventual refusal to communicate, the withdrawing from friends and family, the embittered, resentful feelings at his lack of success despite his efforts—when I read about these depictions, and the way the people in his life reacted to what his depression was doing to him, it’s extremely difficult, and uncomfortable for me to sit in, simply because I understand.

I understand just how difficult it can be, at times, to bring yourself to have a conversation—to open your mouth, and have to use all the strength you’ve got left to push the words out. I understand because of how quickly I can lose my patience with others, and, in turn, how quickly others can lose their patience with me.

I understand the long, dark shadow it feels like you are never going to be able to escape; the black eyed dog outside your door.

It’s extremely difficult and uncomfortable for me to sit in, simply because as much as I do not want to, I see hideous reflections of myself.

*

There’s this quote from Elliott smith, taken from an interview he gave in 1999, where he says, “I don’t feel sadder than anybody else I know. I’m happy some of the time—and some of the time, I’m not.”

Smith was often one to downplay his own mental health when pressed about it, and to my knowledge, there were no interviews conducted with Drake during his career—and near the end, after he had retreated so far inward, I can’t imagine those would have gone very well.

I wonder, though, if he had been interviewed, or had even wanted to speak about his songwriting, the album Pink Moon, or even himself, what kind of candor he would have had regarding his mental health.

There have been a few times since, near the end of January, after I realized Pink Moon was celebrating its 50th anniversary, since sitting down to absorb as much as I could in an efficient way through Petrusich’s 33 1/3 book, and since since listening so intently to an album that I had known, but had not really known before—I have wondered what would have become of Nick Drake if the Volkswagen commercial had never happened.

If the success he was so desperate to achieve that only alluded him during his lifetime, only to arrive nearly 25 years after his death, hadn’t happened.

Would a new generation of sullen young men (like myself) have found Nick Drake another way? And at what point in my life would I have found him? How would I have found him?

And having spent so much time immersed in his life, his death, and his music, would his music, and what he carried with him, still resonate as much with me as it does today?

I sat down, originally, with the intent of writing a phrase I often use when I have written about music over the last nine years—I was going to say that Pink Moon is not a perfect album, but I realize that isn’t true. Its perfection lies in its imperfections—there is perfection in the way Drake mumbles through his vocals, or the way there is a minor flaw, here and there, in the way he picks away at the guitar strings.

There’s perfection in its running time—yes, it is short, but would you want it to be longer? It is the kind of statement that is made, and there is not much else that needs to be said in its aftermath.

There’s perfection in the album’s energy—it is certainly not an “energetic” album, or an “enthusiastic” listen, but from the moment you hear the first strum of his guitar on the titular track, there is a feeling—like, there is more than just Drake’s voice and guitar (and one overdubbed piano melody) poured into this. There is a heft to this album, which is what sticks with you, ultimately. The heft is why this is so important now.

It does capture a moment—one that has become larger than itself over time.

It doesn’t sound rushed, but there is perfection in the presumably minimal amount of takes Drake used during the recording of Pink Moon—perfection in the acceptance of how a song sounded, in that moment, and that it was okay to move on.

I think about the way Elliott Smith, maybe a little aloof, maybe a little sarcastic said he didn’t feel sadder than anybody else he knew. I think about my own depression, and those fleeting moments where things seem a little less awful, and how difficult it is to hang onto those.

“I’m happy some of the time—and some of the time, I’m not.”

At the end of her essay, Anna Borges returns to the idea of continually treading water.

“Do I hope that one day, I won’t feel like this—of course,” she says. “I’m done pretending that this is a fight I’m guaranteed to win if only I try hard enough, instead of something I can, at least, manage. Because I can manage it…maybe there isn’t hope of land in the distance; maybe sometimes there is. Maybe that’s not the point. Perhaps what I’m looking for isn’t land at all, but other people out here with me.

“Trying, and treading, and learning to live in the water.”

1- So, like, this is just a quick aside to mention that I used to work for somebody who regularly referred to my height as being “freakish,” which I didn’t find as offensive as I found it strange, because he was maybe like an inch or two shorter than me.

2- Off The Map was a play written in 1999—it’s structured around the narrative of an adult woman looking back on her childhood, living “off the map” with her eccentric parents in the desert. It was turned into a film the same year I was cast in my college’s production of it. The husband/father in the play is severely depressed, and I had really gone after that role hard, but was cast as an affable friend of the family, which was disappointing. I had beer poured on my head every night in one scene.