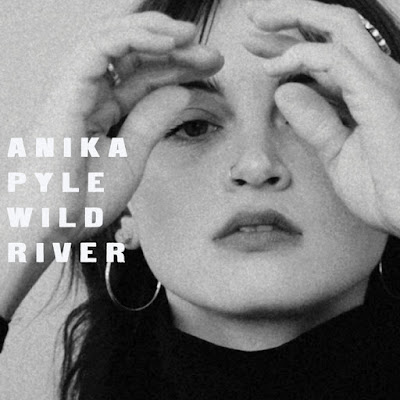

Album Review: Anika Pyle - Wild River

My father emails me toward the end of April, and usually, after his messages taunt me from the “primary” tab of my inbox for around 24 hours, I will move them to the “promotions” tab, so that I no longer have to see his name, or the opening line of the message—it usually begins with “Howdy.”

Maybe, in another day or so after that, I will open his email and read it. And maybe, depending on how I am feeling in the moment, I will respond.

This latest message from my father, sent near the end of April, is to let me know he has retired, or, as he puts it, “until the money runs out,” and that he’s created a blog to document his interest in hiking.

In this latest message from my father, sent near the end of April, he observes that things seem “intense” where my wife and I live, and that he hopes we are doing well. My wife and I live, and have lived, for the last 15 years, south of the Twin Cities, where, earlier in the month April, while a white police officer was on trial for the murder of an unarmed black man, another white police officer shot, and killed, another unarmed black man during a traffic stop.

There were nights of protest and unrest after George Floyd took his final labored breaths in May of 2020; there were nights of protest and unrest after, not even 12 months later, Daunte Wright took a bullet to the chest, fired at close range.

When my father says that things seem “intense,” I want to tell him that, if by “intense,” he means that black men unnecessarily continue to be victims to police brutality and violence, and that people are beyond angry, and beyond exhausted when it happens again, and again, and again, then, yes, things are “intense.”

But I do not believe that is what he means by his use of the word “intense.”

I do not congratulate him on his retirement; I am not moved, at the time, to look into his hiking blog.

I am not moved to do very much anymore. I am, emotionally speaking, barely getting by, and I do not have the capacity, at this point, to respond to him.

His email sits in my promotions folder, the weight of receipts from Bandcamp purchases, shipping notifications, or updates from mailing lists I am on crush his message further, and further down the page.

My father and I are not close.

Yet when I see his name in my email inbox, it is a terrible, terrible source of anxiety.

*

Social media is both great, and absolutely horrible.

Take your pick, really, at the myriad horrible elements from places like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, but it is through those places, or at least two out of three of those places, where I am often introduced to music that is new to me.

Near the beginning of 2020, before everything fell apart, I was introduced to Bartees Strange—roughly nine months before he put out his debut of original material, he began building notoriety for the eclectic collection of National covers1 he was preparing to release. It was through him, I think, unless I am remembering this incorrectly, that I was pointed in the direction of the Philadelphia based emo outfit, Harmony Woods, fronted by the powerhouse vocalist and songwriter Sofia Verbilla.

And it was, most recently, through a tweet from Verbilla, that I was introduced to Katie Ellen, a similarly minded band also from Philadelphia—and from there, through a few more clicks and links to follow, I discovered the solo output of Katie Ellen’s dynamic front woman, Anika Pyle.

*

Near the end of 2017, I was beginning to hit my stride with the kind of pieces I was writing for, what was at the time a fledgling website, The Next Ten Words2—I was submitting personal, observational, and all too often, sprawling essays to my editor roughly every two weeks for publication on the site.

As that year was coming to a close, I was remiss3 to write something reflecting on the year itself—my father’s birthday, in early December, was, for some reason, weighing on my mind at that time, and in sitting down to write what I thought was one thing, as it so often does with pieces such as this, it wound up being about something else entirely.

When it was published online, aside from a few people being confused about the way it ended4, I feel like a lot of folks were simply just surprised I was willing to put something out there that was so honest about my parent’s divorce, my father’s subsequent remarriage, my long-fractured relationship with him, and my own feelings about having children.

Social media is both great, and absolutely horrible, and there are days of the year that I should know to just stay off of it completely—Father’s Day is one of those days, and depending on how irritated I get throughout the day at the sentimental posts or the old photos of people with their fathers—often quaint, grainy, and from decades long passed, there have been times where I would find the link for that essay, and share it again, reminding those who might see it in their timelines that not everybody has a great relationship with their father—or any kind of relationship at all.

The essay, charmingly titled “There is A Monster5 at The End of This Essay (or, Fathering6),” is unfortunately long gone now, like so many of the pieces I had written for other outlets. The site, dormant for well over a year, but still live as of last summer, has now been scrubbed from the internet, and a version of the essay just exists as a Word document on an old laptop.

I am not moved to do very much anymore. I am, emotionally speaking, barely getting by, and there have been years when I struggle more than one might expect to send a short email wishing my father a “Happy Father’s Day.”

*

The thing about Wild River, the debut solo full-length from Anika Pyle is this—it is one of the most intense albums I have ever listened to, but even with as claustrophobic as it can sound at times, and even with as emotionally wrecking as Pyle’s unabashedly personal reflections and lyrics can be, she never allows it to become completely inaccessible.

It’s harrowing and beautiful, and as hard as it might be to believe, and as hard as it might be to listen at times, and not flinch away, those waves of discomfort eventually pass, and it is, as a whole, very welcoming.

The thing about Wild River is that, even without knowing the compelling backstory that shaped its creation, it becomes apparent from within the album’s first few pieces—alternating between proper songs as well as Pyle’s stark spoken word poetry—that it’s about grief.

But knowing the compelling backstory to Wild River assists in building the larger world that the album resides in.

Pyle’s father passed away in October of 2019 from an opioid overdose—she goes into detail in a short essay in the small ‘zine that accompanies the vinyl pressing of Wild River about his lifetime of struggling with addiction and sobriety, and the tumultuous impact that had on her growing up.

Nearly estranged, Pyle and her father reconnected five years before his death. “I felt like I got to know my dad for the first time,” she reflects on this period. “After a lifetime of disconnection,” she continues a short time later in the essay, “we finally found the space to have a meaningful connection and then I lost him forever.”

Wild River is, at its core, not about trying to “process” grief—but it is Pyle taking her grief, and making something out of it that is larger than the grief itself. “We are capable of healing and redemption,” Pyle writes near the end of her essay. “We have all made mistakes we wish we hadn’t. No one is beyond hope or love.”

“This is the universal experience, the vulnerability that unites us as human beings.”

I would stop short of saying that I have, in the past, written about grief extensively, but it is something that has informed a lot of what I write, both in music writing, as well as other pieces. And I would say that it is something that has informed my writing more and more, but it is never a feeling, or a state, that I have directly written about—it is always just a piece of something much larger, or used as a flimsy conceit to get me through while I write about shadowy metaphors or vivid imagery, as I often do.

I am reminded of a conversation, from nearly two years ago, between my best friend and I, that we left unfinished. We were having an exchange about the idea of grief and joy coexisting, and I had told her I thought that it was a wild idea—the very notion of that.

She told me she agreed that, yes, it is wild, but she believed it to be possible. And I told her I didn’t know how somebody could accept both, and that I was uncertain—I still am—if I am capable of allowing myself to really feel joy.

She asked me why I felt that way, but this is where the conversation ended, and in all of the conversations she and I have had since then—some, just two friends making each other laugh; others, serious and heavy—we have never picked this one back up.

In her essay, Pyle also discusses her paternal grandmother—Josephine, who also serves as a major inspiration for portions of Wild River. “On her deathbed, I held her limp and weathered hand and asked ‘Grandma, what is the secret to happiness?’” She responded, ‘Start with joy.’”

*

Musically, it both is, and is not, surprising that Pyle would create an album like this.

Prior to founding Katie Ellen, Pyle fronted the pop-punk band Chumped for four years, before they unceremoniously disbanded at the beginning of 2016—just as she and bandmate Dan Frelly formed an early iteration of Katie Ellen before developing the band’s line up as a four-piece for their only full-length (so far), Cowgirl Blues, from 2017.

For a singer and songwriter who has spent roughly a decade at the front of two very guitar-driven, pop-punk, emo, and “indie rock” leaning outfits, a record so insular, and lo-fi in sound seems like a drastic departure. But Pyle has provided hints at her interest in this kind of instrumentation here and there—her solo single, “Good Woman,” from the spring of 2019, is sparse, powerful, and haunting—the sprawling “The Void,” released the year prior is even more so; and even dating back to Katie Ellen’s debut, on the harrowing, “Proposal,” she strums away at the guitar, unaccompanied, absolutely just belting out heartbreaking lyrics that chart the end of a strained relationship.

Recorded with dusty sounding drum machines and at times whimsical and chintzy keyboards, the instrumentation to Wild River provides a stark contrast to Pyle’s lyrics, and the tone she strikes. Though even with as dark as her material is capable of being, and the places she wants to take us as the record unfolds, there are places where the melodies to the songs are still just as infectious as any pop-punk tune.

Of all the album’s songs, “Prayer For Lonely People,” musically speaking, is probably the most quaint in its arrangement—the layers of keyboard and synthesizers charmingly twinkle while a skittering drum machine beat keeps time. It all sounds incredibly dated—like it came straight from the early 1980s, rather than just last year, but that antiquated charisma provides just the right kind of juxtaposition against the song’s lyrics. “I hope you’re happy,” Pyle begins. “I hope you feel loved,” continuing in the second stanza of the song with a palpable sense of longing—“I know you get lonely…feel me hold you closely even when I’m out of sight.”

“Prayer” is also a striking contrast to the song that comes right before it—“Emerald City,” which finds Pyle more or less pleading with the Earth itself, set against a slow motion rhythm, and synthesizers that aren’t so much ominous, but they create a very heavy weight for her to carry throughout the course of the song.

The guitar—or, at least, the acoustic guitar, is not completely missing from Wild River, but it is not Pyle’s primary instrument for the soundscape she’s created. She does use it to lay the foundation for a swirling, almost dizzying pulse alongside the wheezes of a harmonium on “Blame,” which is one of the early standouts on the album—outside of the instrumentation and her way at creating a memorable refrain out a dark lyric (“I’m doing the best I can with the hand that I dealt myself”), it also one of the first moments on the record where Pyle’s songwriting takes a much more noticeably pensive and bleaker turn—a turn that resonated with me almost immediately.

“Dreading the moment when you inquire how the past few months have been,” she sings, letting her words tumble into the steady pulsation of the guitar. “At the mirror practicing how to trade a little fear for confidence.”

Then, in the second verse, “I’d say I was making do ‘cause most of the time that feels like truth. Tonight I can’t shake the noose—kicked the chair out from under the rest of my life with you.”

Pyle returns to the acoustic guitar near the end of the album with “Monarch Butterflies,” which is probably the most straightforward song on Wild River, in terms of structure, as is “Orange Flowers”—plunked out on warm sounding electric piano chords, it’s also probably Wild River’s most directly devastating. While other moments, across the album, will have specific lines that are intended to emotionally eviscerate the listener, it’s on “Orange Flowers” where Pyle addresses her father, with unbridled sincerity, in his absence.

“I know now people don’t remain the images of their dead body you can’t free from your troubled mind,” she observes. “They become energy—they become light. They become orange flowers shining in the bright sunshine.”

“Orange Flowers,” even though it is not the last track on the album, provides about as much resolve as one can get in an album about grief. “Thanks for never leaving me to wonder if you loved me, or if you were proud,” Pyle reflects. “I know, ‘cause you told me every day of my whole life.”

*

Of the album’s 12 tracks, four of them are recordings of Pyle’s spoken word poetry—plunging you further into the grief that inspired the album, and in a number of instances, she uses these moments to work through the more difficult, or emotionally tumultuous elements that can come from trying to make sense of a loss.

It isn’t to sell the emotional content of the songs short—far from it; but the spoken word pieces allow her to work outside of the constraints of a song—of having to dress things up in metaphor, or find a near rhyme, or put together a refrain to return to. With her spoken word, woven in as interludes, it provides a visceral quality to an album that is already as raw as it could be.

Recorded on what sounds like an actual cassette recorder, Pyle sounds a little distant and distorted as she reads her pieces—and it’s in these spoken word poems that she begins to unpack one of the conceits that runs throughout Wild River, outside of the obvious, and that is the notion of “failure,” which is something that she ruminates on a number of times. “If I hadn’t failed you, I could sleep at night,” she begins, almost confrontationally on “Failure II.” “If I hadn’t failed you, I wouldn’t eat so much,” she continues, though as the pieces unfolds, she pulls back the ways that failure might not necessarily be a bad thing. “If I hadn’t failed you, I wouldn’t know myself…If I hadn’t failed you, I wouldn’t see the beauty of failure.”

Then, just before the album hits its final song, Pyle finds resolution with this element to the record: “Everybody is a failer. Nobody is a failure.”

With as poignant as she can be within her songs, and with haunting phrase turns that linger, and will stay with me for a long, long time, she can do the same with her poetry. Wild River’s second half begins with a lengthy narrative of the last time Pyle saw her father—a Mexican restaurant of all places. And as the piece begins to become more and more frenetic, and as Pyle begins speaking more from the place shower she is desperately trying to grasp onto the fragmented memories before they fade, she delivers one of the most devastating observations from the entire album:

Nothing is insignificant any longer

The loop exists to keep someone alive as long as possible

Their voice, the intricacies of their facial twitching

Their order at the Mexican restaurant

Grief is a grasping for the little things

In the end, they are the only things

Everything

*

When I was a teenager, my paternal grandfather died by suicide.

This was something that I, maybe unconsciously, had suspected for a number of years, but it was also something that was never discussed with me at the time it happened. It was something that was only confirmed, around six or seven years ago, when one of my father’s sisters began sending me, somewhat unsolicitedly7, information regarding family history.

I stopped myself short of saying that in the past I have written extensively about grief but that it is something that has informed a lot of what I write—but without question I will say I have both written about depression extensively, and it also has informed a lot of what I have written and written about, especially within the last two three years.

In 2018, I wrote a personal essay about depression, about the well meant sentiments of people who want have a discussion, or dialogue, or “talk,” or whatever, about mental health, but when it actually comes down to it, the conversations never really seem to happen. Maybe it’s because nobody really knows where to start because it can be and often is so incredibly overwhelming. Or maybe it’s because the well intentioned sentiments were not so much empty, but that when faced with the very notion of discussing something so serious, these well meaning people are too afraid to engage.

Among the things that I attempted to grasp and pull together in this essay, one of them was my grandfather, James, and his death in 1998. He was 67 at the time.

This year, my father will turn 67.

In the brief, clumsy, family narrative that my father’s sister wrote about James, she mentions his younger years spent racing stock cars—“Three (other racers) rammed James into a cement wall, destroying the car and trapping him inside,” adding he was pulled to safety, out of the burning wreckage. That, presumably, coupled with injuries sustained while working as a carpenter took a “terrible toll on his body.”

“He was in constant pain to the point where no medical treatment helped anymore. Depression set in, and sadly, he took his own life.”

In the essay, I reflect on old photographs of my grandfather—one, undated, probably from the 1940s, finds him devilishly handsome with a full head of perfectly coiffed hair, a very thin mustache above his lip, and an unsettlingly intense look in his eyes. His hair is almost all gone in the other photo, form 1976. His eyes, still just as intense, and his mustache replaced by a precisely trimmed chinstrap beard that I thought, somehow, made his smile seem like a sneer.

In the essay, I reflect on what my father’s sister said about James—that “depression set in,” and when I looked at those photos all I could think of is that it was probably there the entire time.

A number of years ago, in my early 20s, I started seeing a therapist for the first time outside of the free counselors provided on campus when I was in college. Within the first session I had been diagnosed, almost immediately, as having general anxiety disorder; around this same span of time, I began having the first of many bouts with terrible insomnia, and because of my long, near-estrangement from my father, when filling out medical history forms, I remember tensing up during the “family medical history” portion, uncertain what to put, if anything.

I had emailed my father to ask a few questions about his medical history, or if he had ever had dealt with any of the same things that I was experiencing. In his response, he mentioned he had never slept well, as far back as he could remember.

He was surprisingly dismissive at the mention of anxiety—“I never saw a reason to get anxious about much of anything,” was what I believe his answer was.

He neglected to tell me that his father died by suicide at the age of 67.

*

This is the only place she does it on the record, and it’s fitting that it is the first track, because in a sense, the titular track to Wild River is a convergence, of sorts, right out of the gate. But it is the place where Pyle merges her spoken word poetry, and a sparse, dark, and uneasy feeling that suddenly gives way to something absolutely gorgeous that, once I really allowed myself to witness it in motion, took the wind out of me completely.

Opening with the collision of an ominous pluck of the acoustic guitar that echoes out cavernously, immediately creating a palpable sense of tension—set against a distant sounding recording of Pyle’s grandmother speaking, “Wild River” gives way, eventually, to the first spoken word piece of the set, “Failure”—which Pyle reads through at a frenetic, almost aggressive pace and tone, where she dissects the idea of fear, saying that it is karmic and if you don’t “pick that shit up and repurpose it, or give thanks to it, it will haunt you from place to place, preventing you from ever fully realizing your potential for the rest of your one, tiny, precious life.”

That kind of call to arms is place in contrast with the song that eventually comes tumbling in. After very deliberately letting the words of the first lines of the song come in over the tense pluck of the guitar strings, creating a notable dissonance, before “Wild River” opens itself up, and the lush instrumentation comes in.

The song itself, presumably both a rumination on the notion of “living without having lived,” as well as a reflection on her grandmother, unfolds delicately and beautifully, allowing Pyle to let her voice soar to the highest range she uses on the record, making for a jaw dropping, gorgeous opening piece full of poetic phrase turns—“I like to clean the kitchen at parties…I never flirted with danger—in fact, I have an arranged marriage with the meticulous routine of rising each day before six o’clock in the morning,” she sings, before the final poignant line: “I wanted to be a wild river, but I am still a country creek.”

Wild River closes with what is probably its most pensive, or melancholic sounding song—and with an album as emotionally charged as this one, it is difficult to bestow that kind of descriptor onto just one. But the difference between “Windy City” and other moments found throughout, like “Haiku For Everything You Love and Miss,” which is hands down the album’s finest track—is that song is just beyond heartbreaking, while “Windy City” has a bittersweet, swooning feeling to it, thanks in part to the dreamy, atmospheric undercurrent that Pyle slowly strums her guitar over the top of.

And like the titular, opening track—the idea of a “wild river” is returned to on “Windy City” as well, it is a song where myriad elements converge once more. It ends with another spectral recording of her grandmother speaking, imploring her granddaughter to “go with love,” which is another one of the themes that resonate from the album as a whole; Pyle layers her vocal tracks, with one repeating the phrase coming at the tail end of the song’s lyrics—“Nobody knows me like you do,” and with her other track, she slips into another spoken word piece—a reflection that ends with a question that is never answered. “Have I become dull to the wonder of the world?,” she asks at first, and then in the end, “How even through it all—the breaking down…the relentlessness of shame and utter idiocy of being human we still seek joy and find it over, and over, and over again?”

*

There was a moment somewhat recently when I put together something that, I think, I knew all along but had not so much failed to recognize but did not maybe give as much acknowledgement as I could to, but I put together that three of the women in my life have all lost their fathers.

A part of me wonders if that means something larger than just being purely coincidental, but that part of me is also unable to unpack, or understand, the larger meaning, if there is one to be found.

And it is in moments like this, when I put together this fact, and that the three of them have this in common, that there is something within me that isn’t remorseful for the way things turned out between myself and my father, or that I second guess myself in the lack of a relationship I have with him—but I begin to ruminate on the idea that there are people in my life who do not have the opportunity to have a relationship with their father at this time, and I do have that opportunity, and have had that opportunity for years, and I have chosen not to take it.

I ruminate on this, but like so many things, I am uncertain what to do with it.

I would stop short of saying that I have, in the past, written about grief extensively, but it is something that has not only informed a lot of what I have written, but it is also something that has more or less shaped my life within the last decade, and will continue to shape my life for the indefinite future to come.

Grief is something that often takes my breath away, day to day, and I have gone so far as to try and trick myself8 into believing I have “processed,” only to have not been able to maintain that facade for very long.

What is tough to keep in mind is that there is no right way, or wrong way, to try and work with, or even work through your grief if you live with it daily the way that I do. And the thing that my therapist is often reminding me is that grief is non-linear.

There are so many of them, but I often return to one of my favorite lines from Hanif Abdurraqib—“We are both in the business of ghosts.”

Grief is something that often takes my breath away, day to day, which is why I was drawn to Wild River in the first place, after reading the description on Pyle’s Bandcamp page. And out of all the moments on the album that resonated with me—there were, obviously, many of them, for a number of reasons, the album’s centerpiece, arriving at the end of Wild River’s first side, is the song that impacted me the most.

I am uncertain, at what age, I learned what a Haiku was—maybe in grade school, and it’s a fascinating set of boundaries to express yourself within, forcing the writer to be more selective with the words they use, how many of them they are able to use, and how they choose to use them.

Five. Seven. Five.

The first side of Wild River closes with “Haiku for Everything You Loved and Miss,” which is, out of the whole album, the most viscerally sad and chilling, based on both the atmosphere Pyle creates with moody, sparse instrumentation, as well as the way her lyrics are strung together, which is, as you may have anticipated, through a series of Haikus.

Pyle, of course, takes a few liberties with traditional syllabic structure of a Haiku—five, seven, and five, but her commitment to putting together such intense lyrics—perhaps the song that confronts grief and loss the most head-on—through these carefully crafted verses is beyond impressive.

She begins the song by drawing a stark contrast on her own existence—“Everyday I think this bed is a rented bed,” she sings slowly and delicately. “I do not belong.”

“The bed herself is a fertile place of comfort, but I am barren,” she continues, before making a brutally honest observation on waking life—“Morning splashes in, I wake gasping for air…another day to wish there were no more days here—somehow hold on.”

For an album that is so dark, and so insular in sound, you would not thing that there would be “hooks” or elements of infectious pop songwriting worked into any of this, but that is another surprising thing about Wild River—it’s dark, yes. So dark. But it’s memorable. Not just because o what it’s about, and how it lingers, and will linger, long after you are done listening, but because Pyle, as a songwriter, is intelligent enough to still work something “catchy,” for lack of a better word, into some of these, even if the thing that is repeated, or that she returns to, is one of the starkest things on the album.

“Haiku,” eventually, becomes a mantra—set against the low pulses of a drum machine, offset near the end by an additional percussive blip that reminded me of Phil Collins’ early experimentation with drum programming on “In The Air Tonight,” Pyle mashes down long, distended, mournful sounding synthesizer keys, creating not an ominous tone, but one that is somber, as she works her way to this reckoning—“Everything you loved and miss will never be the same as when you loved it.”

*

Pyle’s father passed away in the fall of 2019, and Wild River is not so much an album made in response to the pandemic, but it was made in response to both the grief she found herself in, as well as the time and isolation she had. “We’ve all lost so much this past year,” she writes in a short note about the album. “Loved ones, jobs, houses, in may ways, life as we knew it. By the time the pandemic hit, I was already deep into a grieving process and learned you can’t stubbornly resist a wild, unpredictable, uncontrollable river, no matter how desperately you battle the current.”

Wild River is an album that isn’t for the faint of heart, but it is also an album that literally comforts you as you work through whatever pain, or grief, has brought you to it, with Pyle allowing you to cry as much as you need to during the journey you take with her every time you listen.

She says it’s about learning to let go and “move forward from grief steadfastly with love.” It is a beautiful artistic statement—it’s about the fears we can have within, but this album, itself, is fearless in how it graciously handles this emotional territory.

I am still, and probably always will be, searching for the place where I am able to allow both grief and joy exist together. Most days, especially within the last couple of months, I am uncertain where to begin.

Go with love.

Start with joy.

1- In February, just before everything went to absolute shit, Bartees Strange released his haunting, beautiful cover of “About Today.” The full EP of covers, Say Goodbye to Pretty Boy, was released later in the spring, then the vinyl edition, delayed due to the pandemic, arrived I think in the summer? Either way, I had intended on writing a piece on it, but found I was not able to because a) everything was falling apart around me and b) because I found I was really confused by the roll out of the EP—the vinyl edition of the EP features a specific set of the covers, but sequenced in a different order than how they appear digitally, and even then, he was releasing additional covers off and on (as well as two original songs) as part of the early Bandcamp Friday offerings. I had also intended on reviewing his full length but by October, when it was released, I was suffering from severe burnout from literally every element of my life, and it just didn’t end up on the list of things I was able to really sit down with. Sorry Bartees, if you are reading this.

2- I figured it would be entirely too difficult to explain The Next Ten Words as well as my contentious relationship now with my former editor in a concise way that would have fit into this piece, so, as a footnote, here it goes: In 2013, I began writing short, observational humor columns for a monthly magazine called the Southern Minnesota Scene. I continued to do so until mid-2017 (and the pieces stopped being all that funny, truthfully) when my editor was fired unceremoniously while he was attempting to put together the next issue of the publication. Shortly after he was let go, he launched a work in progress version of what would later become The Next Ten Words, and after about a month of two of little to no communication to the writers regarding his dismissal, or who was editing the magazine going forward, I realized I was not going to be able to continue writing for it. I started writing for The Next Ten Words, and continued to do so until October of 2018, when the site was hacked and my editor, for around a month or so, lost the ability to access his own website and make updates. That happened a few more times, and by the end of that year, I told him I had to walk away from it, and writing for him, because his inability to publish my material was causing a huge problem with the way I was balancing my workload of non-music writing and music writing. I have, obviously done a lot less directly personal and non-music writing since 2019, but I think there has been a place where the music writing has become more personal—they just aren’t observational essays, or whatever.

3- The December issues of the Southern Minnesota Scene were always structured around the theme of the “year end,” and I was often encouraged to put together something on the impending winter doldrums or reflecting on the year that was wrapping up. The first time around, it was not a chore to do; the second time around, it was an enormous chore; the third and final time, I ended up writing about grief and death.

4- I specifically remember my boss at the time talking about something else entirely with me at work, stopping mid-sentence, and asking me a question about the ending of essay—and I can recall an acquaintance of mine, who I am truthfully not that fond of, chiding me on Facebook about the way it ended, because he didn’t get it, or it wasn’t wrapped up nicely.

5- The title, and one of the flimsy conceits I tried to work in, was based around the Sesame Street related children’s book, There is A Monster at The End of This Book.

6- This is a reference to the song, “Fathering,” by Mark Mulcahy.

7- I say “somewhat unsolicitedly,” because it’s not like this shit just started showing up at the house unexpectedly. She asked my father if I would be interested in receiving this information, I foolishly agreed to it thinking it would be like one envelope or whatever and it wound up being email upon email and envelope after envelope, arriving with some regularity. It became completely overwhelming, and it was also around this time, near the end of 2014, that I started a new job that, within a month or two of settling into it, I realized was probably a mistake and was causing me a lot of stress; it was also around this time that a member of my family was slowly dying—something that I had written about, of course, in an essay that was published on The Next Ten Words.

8- At the end of 2014, and beginning of 2015, I tried like four or five sessions of something called EMDR, which is an experimental form of therapy. I was not entirely fond of the woman I was working with—she seemed aloof at best and disinterested in helping me, and because this was during the same period of time when I was sinking into the stress of a new job, and anxiety over a sick family member, I convinced myself, or at least told her, that I was feeling better and that the therapy helped me work through my grief. I knew deep down that it wasn’t true.

Wild River is available now as a limited edition LP as well as a digital download.