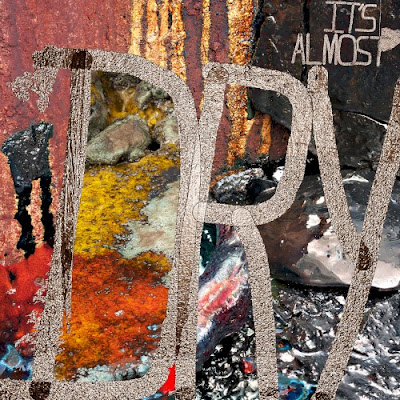

Album Review: Pusha T - It's Almost Dry

For about half of 2020, and into, like, the first four or five months of 2021, the building I worked in was under construction. And there were days where it was, in retrospect, not that bad. Or, looking at it a different way, it could have been, and was going to become, much worse.

There were days when I had to work around construction-related inconveniences—both minor and significant, and at the moment, they were all extremely frustrating regardless of the scope. And then there were the days where it was absolutely intolerable—often subjected to situations or environments that many would deem extremely cruel to expect someone to work within and unsafe.

And I bring this up because there were many days throughout that period when I had no choice but to listen to the sound of concrete grinding.

If you are unfamiliar with what being exposed to that kind of noise is like, take a moment and imagine the worst sound you can think of—harsh, loud, et al. And once you’ve thought of that sound, realize you are nowhere close to how viscerally awful it is to be more or less trapped in a building where that is happening—sometimes for hours without end. Even with ear protection, there were times when the noise was so sickeningly loud, that I was confident I could feel my brain rattling inside my skull.

And I bring this up because, there was a point, when there was going to be a day of concrete grinding, I had been instructed to alert my staff to this, so they could have time to, like, mentally prepare. And to a young woman who worked in my department, I gave the heads up that there would be some grinding—“not the good kind, like the song by Clipse.”

The realization that you are washed inevitably comes for all of us—but it was a sobering, generational moment when this young woman—she was probably 22 at the time—told me she didn’t understand my reference.

She did not know the song “Grindin’” by the group Clipse. And perhaps it is erroneous of me to presume that everyone, regardless of their age or upbringing, is familiar with that song.

“Clipse?,” I tried again. “You know? The duo that Pusha T was in with his brother Malice?”

And it was a sobering, generational moment when this young woman responded by telling me she had no idea Pusha T had ever been in a duo, and then implied her only point of reference for him, and his music, was his 2018 album, Daytona, which she, apparently, really liked.

*

If you subscribe to, and if you don’t even necessarily understand, the idea of the multiverse, just know there is a version of me, out there, somewhere, that is still as passionate and interested in contemporary rap music as I was roughly nine years ago—specifically passionate, interested, and enthusiastic about Pusha T.

And maybe it exists in the same alternative universe—but even it if doesn’t, if you subscribe to the idea of the multiverse, there is also, more than likely, a version of Pusha T who would eventually release the long-gestating album King Push, rather than ultimately scrapping it.

There is a version of Pusha T who would not go on to release Daytona; a version who did not let himself become caught up in the unhinged publicity stunt of Kanye West producing and releasing five albums in five weeks during May and into June of 2018.

Since truly arriving as a solo artist in 2013 with the blistering My Name is My Name, I am not suggesting Pusha T’s career since then has been one of diminishing returns. That is simply not the case. However, it has, at least for me as the listener—and now, more of an analyst than a fan, been uneven at best and full of what I consider frustrations.

Two years after the release of My Name is My Name, Pusha T returned with the cumbersomely titled King Push—Darkest Before Dawn: The Prelude, which at the time, I did not believe to be a canonical sophomore album. Marketed as a collection of songs that were not deemed the “right fit” for the, then still, forthcoming King Push, seven years later, it is, at least in Pusha’s eyes, his second studio album.

By the time Daytona arrived, King Push, as a heavily mythologized album, let alone just an idea, or a notion, no longer existed.

I am remiss to say I was disappointed by Darkest Before Dawn, but at the time of its release, which was at the very end of 2015 and, if I remember correctly, at a very low point for me personally, and due to that, I think I was in a place where I was unable to invest myself in listening to it as a fan, and I wound up listening to it only to write a review—finding it was something that I was just not as interested in, or moved by comparatively to the way I had, just two years earlier.

It was an album that, following hitting “publish” on a 732 word review1, I doubt I revisited much, if it all until today—like, just now, while reflecting on the past nine years as a fan—once extremely enthusiastic, now passive at best, of the rapper born Terrence Thornton.

Daytona met a similar fate—shortly after its release, I felt, for some reason, compelled to pre-order the LP, which arrived at my door maybe two or three months2 later, and if I remember correctly, I listened to it a fair amount of times during the summer, and into the autumn of 2018. Unlike Darkest Before Dawn—an album whose songs retained almost no memory of, there were specific songs, or at least certain moments, from Daytona that I thought about with some regularity, like relentlessness within the opening moments and the jittering bounce that bridges the gap between the verses in the first track, “If You Know, You Know,” or the eerie, menacing, and incendiary closing tune, “Infrared.”

But, beginning in 2019, there is a high possibility that my copy of Daytona remained filed in the P section of my collection, and would not see the light of day for another two years3.

*

What does it mean to be “Cocaine’s Dr. Seuss?”

And is it similar, at all, to being the “L. Ron Hubbard of The Cupboard?”

Thornton refers to himself as both of those things—the latter on “Crutches, Crosses, Caskets,” from Darkest Before Dawn; the former, from “Let The Smokers Shine The Coupes,” the second track from It’s Almost Dry, the fourth solo studio album from the rapper known as Pusha T.

The recent arrival of It’s Almost Dry was both a surprise, and not—a surprise because the album was announced on a Monday, and was available at the end of that week, on a Friday; and not because of the gradual rollout of both advance singles and vague information about the album before its release. The song “Diet Coke” was issued in early February, followed two months later by the Jay-Z feature “Neck and Wrist.”

The album had a title, and its release seemed imminent, but I was not sure just how imminent.

Daytona’s brevity (seven songs and 21 minutes) was due, in part, to Kanye West’s oversight in the creation of the album—all of the albums he produced in Wyoming during those five weeks in May and into June of 2018 were, like, seven or eight songs at most.

But, similarly to Darkest Before Dawn, which was barely over a half-hour, It’s Almost Dry also does not overstay its welcome—12 tracks and 36 minutes in length. With production duties split between West and Thornton’s longtime collaborator Pharrell Williams, structurally the album stops short of sounding “unfinished,” but rather, there are places where both a song can feel like it’s just finding its momentum, then it’s is seemingly over as soon as it began; or, a song can feel like, if it continued, it would be beleaguering its conceit—that what was said needed to be said, and there was no need to stretch the idea out further.

Even in the days when Thornton was rapping alongside his brother, performing as Clipse—especially on the duo’s second album, Hell Hath No Fury; there was a dark and claustrophobic nature to both the music itself, as well as the vivid narratives constructed. And for the most part, that has not changed. It’s Almost Dry, absolutely dizzying in just how self-aggrandizing it can be, and as one might anticipate, extremely gritty and bleak in what it depicts lyrically.

A stark and often uncomfortable juxtaposition in the way it provides examples of the lavish, with examples of utter desolation.

*

With two marquee-named producers behind the boards for It’s Almost Dry, you may think the album might, at times, lack cohesion in its overall aesthetic. It doesn’t, really—but because both Pharrell Williams and Kanye West have such trademark elements to the way they produce and orchestrate tracks, as the album unfolds, it is relatively apparent which producer is responsible for which set of songs.

The split between producers is surprisingly even, with each taking on six of It’s Almost Dry’s 12 tracks. West’s first contribution is the album’s third track, “Dreaming of The Past,” and based on how the song is constructed, his involvement should have given itself away almost immediately—returning to the kind of innovative interpolation that made him a household name nearly 20 years ago, West chops up, and shifts the pitch and tempo of the Donny Hathaway cover of John Lennon’s “Jealous Guy,” a technique he deploys again few songs later, and perhaps a little less impactfully on “Just So You Remember.”

“Just So You Remember” is among the more skeletally arranged tracks on It’s Almost Dry, relying on a simmering sense of tension from the blippy rhythm, along with the way Thornton’s lyrically delivery grows in intensity the further he gets into the song, until it’s almost through gritted teeth. Pulling a sample from the 1970s progressive rock song “Six Day War,” by Colonel Bagshot, the way the samples are placed within the song seem a little shoehorned, and it, at least to me, ends up being just not as interesting to hear, seeing as how it was already used with success 20 years ago on “Six Days” by DJ Shadow.

The final production nod to the “old Kanye” is the album’s first single, “Diet Coke,” which features subtle, glitchy, vocal samples that have worked their way into the beat, though they are not lifted, or at least not credited, to any one specific song.

Of the other West produced, or co-produced, tracks on It’s Almost Dry, the late-arriving “Hear Me Clearly” is one of the album’s more memorable, built on a thundering and crisp rhythm, and an eerie, extremely menacing, and warbled sounding keyboard melody that runs throughout the song’s entirety.

And what I have realized now is that neither West, nor Pharrell Williams has their respective stranglehold on the sound of popular rap music the way they both did, in their respective corners, in the early 2000s. Maybe West’s production was not as widespread, but when Williams was still regularly working with this Neptunes producing partner Chad Hugo, the two of them were responsible for shaping so many iconic sounds—and nearly all of them were built out of a particular kind of sound, featuring heavy emphasis on percussive elements and an array of buzzy, dreamy synthesizers.

I am uncertain if, overall, Williams has moved away from those elements within his production, and I hesitate to say he has for his contributions to It’s Almost Dry; or, at least, he hasn’t within the album’s first song. The sprawling, surprisingly personal4 narrative of “Brambleton” features a somewhat dreamy synthesizer melody that drifts throughout, skittering across the top of a rumbling baseline—though Williams’ previous interest in live percussion, or at least a very specific kind of drum sound, has changed over time. Here, the beat, seemingly coming from a drum machine, simply clicks along with minor if any flare or flourishes.

Williams does something similar on the album’s second single, the slow-motion “Neck and Wrist”—though, on this track, there are two opposing synthesizer lines that, when you focus on how both of them move around one another, can become disorienting.

But the first song you hear Williams’ production on while listening to It’s Almost Dry is not indicative of his other work on the album—the days of the compelling oddball whimsy one could anticipate from his involvement in a song are over, and the truth is many of the tracks he is credited for on the album, especially in its second half, are just not that interesting, or at least lack any genuine enthusiasm behind them—save for the frenetic, pulsating, and at times oppressive “Let The Smokers Shine The Coupes,” which is, at least musically, the most energetic song of the otherwise relatively reserved set.

*

Until recently, I was unaware that Variety, a publication or news outlet, or whatever, that I most associate with film and television, apparently also provides some coverage of music—reviewing roughly one album a week. And the only reason I even know this now is because a pull quote from Variety’s review of It’s Almost Dry began making the rounds on Twitter the day of the album’s release.

And the reason this review was even making the rounds on Twitter, or at least the part of Twitter I inhabit, was because people were pointing out the flaw within the conceit of the writer’s take on the album. His complaint was that 20 years following Clipse’s debut full-length release, Lord Willin’, Thornton, now well into his 40s, married, and with a young child, is still rapping about cocaine.

The writer—in an enormous stretch, mentions the growth shown within the lyrical content of Jay-Z’s 4:44, and expresses his disappointment that Thornton did not use this as an opportunity to show some growth of his own.

Yes, Terrence Thornton, the rapper known as Pusha T—the man who refers to himself as the “L. Ron Hubbard of The Cupboard,” or even more boastfully, the “Kim Jong of the crack song,”—he is still rapping about cocaine.

Because, what else do you expect him to rap about?

What else did you expect an album titled It’s Almost Dry to be about?

Lyrically, as one might anticipate if they know anything about Thornton and the trajectory his lyricism has taken since arriving as a solo artist nearly a decade ago, It’s Almost Dry is unrelenting in its descriptions of the manufacturing and selling of drugs, the threats of violence that surround said manufacturing and sales of drugs, and the kind of luxuries one can afford with both the money earned from both the rap game and the crack game.

In his interview on “Desus and Mero,” before the release of It’s Almost Dry, Thornton isn’t dismissive of the descriptor “coke rap” being applied to his music, but he also explains there is more to it than that, and that the drug references are, at times, extended metaphors.

Throughout this album’s 12 tracks, it doesn’t get tiresome, per se, hearing Thornton talking about cocaine, or crack, or acts of violence, or all of the nice things he’s been able to purchase through his various channels of income, but it can get to be a little much. And throughout his career, both as a solo performer and when he was still rapping with his brother, Thornton, even when yet another reference to cocaine can get to be a little much, is also capable of being wildly clever with his lyricism—the wit, often, isn’t exactly lost the first time you might hear it. Still, the intelligence in wordplay and even the sense of humor found are revealed once you can sit with the songs after additional, close listens.

Perhaps the most obvious example of this is in “Dreamin’ of The Past.” A song, even with all of its faults, includes a line that had me doing a double-take for just how obscure, or at least incredibly specific, of a reference Thornton casually tosses in—“My weight keeping’ ni**as on the bikes like Amblin5”; then, near the end of that verse, Thornton returns to the idea of where he ranks within a list of the “top five” best rappers—he does this first on Daytona, again in another spectacularly clever lyric (though it directly references a skit from the “Chappelle Show6,” so I am uncertain how well it has aged). Here, he proclaims, “You hollerin’ ‘Top Five,’ I only see top me.”

*

It’s Almost Dry is not a bad album, but what is preventing me from saying it is good, or even great, is how I am unable to look away from the pronounced issues I take with parts of it—the two most glaring are the featured appearances by Jay-Z and Kanye West.

Sometimes I think about Jay-Z’s verse on the song “Monster,” the feature-heavy track nestled somewhere within West’s opus My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy. Of all the verses on that song—the most iconic going to a then relatively unknown Nicki Minaj, Jay’s is the most puzzling—unintentionally funny, and the weakest in the song.

At 52, Shawn Carter is, famously, not a businessman—he’s a business, man, and he is over 25 years removed from the young and hungry drug dealer turned rapper who graced the cover of his startling debut, Reasonable Doubt. Similarly to how nobody expects Thornton to rap about something other than drugs, nobody is expecting Carter to begin rapping about drugs again. But what does this Jay-Z rap about? He has more wealth than I can comfortably fathom, is married, and a father of three—this is in jest, of course, but it seems like rapping about asking his kids not to touch the thermostat isn’t out of the question.

The problem with Carter’s contribution to “Neck and Wrist” is not really what he’s talking about, but it’s how he’s doing it. Something seems off about the delivery—he’s not off rhythm, not exactly, but there is a wavering I noticed from the first time I heard the song, and it returns with each subsequent listen. It’s like he’s getting just a little too ahead of himself, then is suddenly a little behind, and I feel like it is most noticeable on the lines, “Y’all spend real money on fake watches—shockingly they put me on lists with these ni**as inexplicably.”

Even with the faults in “Neck and Wrist,” I still laugh, every time, at the subtle humor of, “We got different Saab stories—save your soliloquies.”

As a featured performer, West appears on two of It’s Almost Dry’s tracks—which unfortunately means his attachment to both as a rapper, rather than just a producer, means there are controversies within each appearance.

Four years ago, in the months leading up to his “Wyoming Sessions” run of album production, West was famously going through some things—and it is difficult to write about the Kanye West that existed over the last five or six years, because I am sympathetic to the notion that he is probably dealing with several mental health issues that, perhaps, are not adequately being addressed. But in the spring of 2018, with his full support still behind Donald Trump, West released a piss-take of a track where his entire verse was him saying the words “Whoopty poopty scoop, poopity scoop,” over and over again in rhythm with the beat. And because everything at that time was happening so quickly, and so last minute, he references those nonsensical lyrics with his guest verse on Daytona’s “What Would Meek Do?”

West’s verse at the end of “Dreamin’ of The Past” feels tacked on at best, and with the tone it takes as he reaches the final few lines, he brings that big “divorced dad” energy to the song.

After taking a moment to flaunt his wealth and what it can get him, he reminds the listener that he is in the middle of a very public, and very tumultuous dissolution of his marriage to Kim Kardashian—“Born in the manger, son of a stranger,” he mumbles shortly before the song’s ending. “When daddy’s not home, the family’s in danger.” And at first, before staring at the alleged lyrics to “Dreamin’ of The Past,” annotated on Genius, I misheard this lyric and thought it was much worse—“When dad is at home, the family’s in danger,” as a reference, and sneer in the face of his continued erratic behavior toward Kardashian, and the person she’s currently (and allegedly) romantically involved with.

Either way—West, seeing himself as the father here, home or not, it’s difficult to hear, an incredibly stark line that casts a depressing shadow over the song.

West turns up again in the album’s latter half on “Rock N Roll,” one of It’s Almost Dry’s more forgettable tracks, which also features an appearance by Kid Cudi. The controversy surrounding this song has nothing to do with any of its lyrical content, and is more with what’s happening in West’s personal life. His relationship with Cudi—born Scott Mescudi, has been notoriously volatile, and has most recently (as in the like the last month or so) had a falling out over Mescudi’s friendship with comedian Pete Davison—the person, as of right now, who is in a relationship with Kim Kardashian.

The song itself was recorded in 2021—long before this current personal issue created a rift, and Mescudi claims he only signed off on the song being included on It’s Almost Dry because he and Thornton are still on friendly terms.

*

With as short as It’s Almost Dry is, the thing that, at times, can make it seem like a long, or slow album is, I think, just how uneven it winds up being—which can make for a long, slow, and frustrating listen with all of these brief flashes of brilliance or intelligence throughout.

But even in that frustration, the thing that makes the album worth sitting with, and the most exciting part of It’s Almost Dry is the closing track, “I Pray For You,” which boasts the return of Thornton’s older brother, Gene—when still a part of Clipse, he performed under the name Malice. However, he changed it to “No Malice,” roughly a decade ago following his decision to leave the duo, and convert to Christianity.

Following the dissolution of Clipse, the brothers Thornton were not estranged exactly. Still, it created some tension that would eventually be resolved when Gene presided over his brother’s wedding in 2018.

The elder Thornton is credited on the enormous, unrelenting “I Pray For You” as “Malice” once again, and it is an absolute thrill to hear the two of them reuniting in this way, with Malice’s verse, as one might anticipate, completely stealing the show—both because of the sheer surprise at his appearance on the album, and within the way he finds the space between his deeply rooted spiritual beliefs, and his long-dormant connection to the streets, then delivers his lyrics from within where those two polar opposites begin converging.

“Still fightin’ demons, see, that curse is now my gift,” he says as his verse gets underway. “Secrets die with me—that’s as deep as the abyss, that is no coincidence. When I was in the mix, opened up your nose like I was cutting’ it with Vicks….” Then, as his verse, and the song, near their end, “Watch my brother ‘round you bitches, I know he pretends. I greet you with the love of God but that don’t make us friends—I might whisper in his ear, ‘Bury all of them.’”

“I Pray For You” is not being touted as an official return of Clipse as an active duo, but there are subtle hints within both Pusha’s and Malice’s verses that imply the door is open now. “Light another tiki torch and carry it again. Back up on my high horse—it’s chariots again. Put the ring back on her finger—marry it again,” Malice commands shortly before the song concludes. And in the first verse, Pusha, after opening with reference to a phoenix rising from the ashes, before referring to his decade as a solo artist—“The past ten years screamin’ ‘Uno!,’ then sidestep back into the duo. The kings of Pyrex, I’m my brother’s keeper if you listen and you dissect….”

With surprisingly reserved production from Kanye West—his involvement in a song that is steeped within religious imagery is unsurprising, “I Pray For You” begins with a scratchy, soulful falsetto from featured vocalist Labrinth—a singer who is most known for his association with the music from the HBO program “Euphoria,” backed by mournful church organ, the song then shifts into dissonant, slightly warped, bombastic blasts from the organ, setting a dramatic, though sparse, stage for the brothers to perform on top of. There’s no chorus, no percussion underneath, and the exhilaration the song creates through the scope of its arranging and the slight return of Clipse is palpable.

*

It would have been around the time that My Name is My Name was released—an album that was regularly played in the car, or in the house as 2013 was coming to an end, that my wife began using the descriptor, “The Pusha T ‘Yucky’ Noise.”

And I am guessing that, if I were to search for that on the internet, I’d find the exact sound she’s talking about spelled out phonetically, or maybe a different way to describe it. But famously, for the bulk of his career, at least before It’s Almost Dry, Thornton would often create this guttural sound from the back of his throat, projecting it out with haughty disgust. I would be remiss to call it an “ad-lib” within the way he delivers his lyrics; it’s more of a punctuation device.

Yes, Thornton still raps about drugs, violence, and expensive wristwatches—and yes, you can be disappointed that he hasn’t grown out of that, but even if there isn’t any lyrical growth on It’s Almost Dry, there are noticeable changes throughout. In his interview with “Desus and Mero,” he seemed more reserved—maybe he was just tired. Maybe having a son less than two years old is exhausting. But there was a stoicism in the way he spoke that you can hear within the album. He was never unhinged, or chaotic as a rapper, but there was an exuberance—you can hear it in the first two Clipse records, and on My Name is My Name. But here, there’s a reserve that can, and often does, create a sense of brooding tension. I don’t want to say he lacks energy as a performer, but it’s perhaps a different kind of energy.

Yes, Thornton still raps about the making and selling of crack, horrific acts of violence, and a life of luxury that I will never know—and yes, you can be disappointed that he hasn’t grown out of that, but even if there isn’t any lyrical growth on It’s Almost Dry, there are noticeable changes throughout. And while it may be a small detail, the most apparent change in Thornton’s persona as Pusha T, is the total absence of the “Yucky” sound. It has, unfortunately, been replaced with a high pitched, unsettling laugh that is inspired by Joaquin Phoenix’s characterization of The Joker in the 2019 film of the same name—with Thornton going so far as to even refer to the character’s “real” name in the song “Rock N Roll7.”

It’s a curious turn—immersing himself so far into the Joker film that it, apparently, was just regularly playing with the sound off in the studio while Thornton was working on the album. And within Thornton’s lyrics—reflectively, both still as a member of Clipse, but mainly as a solo artist, he had played the role of the antagonist in his narratives rather than a protagonist, simply because of the underlying incendiary nature of his lyricism and the way it’s delivered. But there is a fine line between merely antagonizing, and being an actual villain, and the turn here is that Thornton wants us to believe that he is a rap music villain of sorts. It isn’t implausible, but as a narrative device, at least for me, it isn’t a necessary element to the overall portrait It’s Almost Dry paints. The realistic grit of the album does enough without it.

*

Do I still like rap music?

The easy answer is “yes,” but it is also more complicated than that.

In the outline for this piece, once I found a way into it after a few days and got over the first thousand words or whatever, that question, or if I still “like” rap music, was one I wrote down as something that, if I was able, should be explored.

The other day, I realized that in 2021, I didn’t write any pieces about recently released rap albums—and it took me a little while to recall the last time I sat down and deeply analyzed any releases within the genre. The first two that came to mind were from 2019, when Billy Woods bookended the year with two albums—one of them incredibly; the other, a little less so. The last time I, in earnest, wrote about rap music was throughout 2020. One of the pieces was a reflection on both the tumultuous times of May and June of that year, as well as a recent LP from an artist I genuinely and thoughtfully enjoyed who would, unfortunately, around two months after that album’s release, go on to be accused of sexual assault.

And because I struggle to separate the art from the artist, it’s an album I have not been able to revisit, and he is an artist I have been unwilling to continue following the career of.

Do I still like rap music?

The answer of course is yes—the genre, in all its twists and turns throughout history has played an enormous role in my musical upbringing.

The answer is yes, but what I have come to know about myself is that I like and often return to a specific kind of rap music—from a very specific period of time and geographical location8, and that despite the efforts I put in, especially in the early days of becoming a fledgling music writer, I am simply unable to research every artist I see named in a headline, or make and have the enthusiasm to listen to an album—and even if I do find a new release I enjoy elements of, is it something I feel I would be able to make the space for to write about it?

Rap music, and especially depending on the artist, can be challenging to unpack and analyze, and I do not always have the confidence that I would be able to analyze something9 as thoughtfully as it deserves.

The expression I think I meant to introduce much earlier in this, but forgot, as a way to describe the place that Thornton is operating from on It’s Almost Dry, and perhaps has been operating from for a long time now, is one of “creative non-fiction.” And there is, of course, always the line that becomes blurred in a genre like rap where it is difficult, and at times impossible, to distinguish where reality ends and an exaggeration begins. But that kind of effortless ability can make for compelling storytelling, even if the story's thematic elements are similar to what you’ve heard before (i.e., cocaine.)

Do I still like rap music? The answer is yes. And somewhere, if you subscribe to the idea of the multiverse, there is a version of me out there that is still just as enthusiastic and passionate about contemporary rap music as I was around nine years ago.

There is a version of me that would have probably enjoyed It’s Almost Dry a lot more than the version of me—the one who has spent over a week and over 5,000 words analyzing, is capable of. It’s challenging to walk the line between making something that somehow transcends and becomes “timeless,” and creating something that is representative of the moment you find yourself in. Because of the nature of its creation, Daytona’s most fatal flaw was that it was very of the moment—rooted too deeply in a time and place that it was unable to find a way beyond that. It’s Almost Dry struggles to find that balance—you want it to become something more significant than itself, but there are myriad things I can see holding it back from where it could go.

A dark album mostly about dealing drugs, on paper at least, doesn’t seem like it would be “infectious” to listen to, but because of Williams’ and West’s ear for pop music, there are moments throughout that wound up becoming stuck in my head. It may, truthfully, be an album that I do not return to often, or ever, now that I have listened and been able to gather my thoughts. And as uneven and frustrating as I found It’s Almost Dry the longer I spent with it, those brief, bright flashes of brilliance were compelling enough to keep me listening for now.

1- Sometimes, I have to just laugh at the absurdity of it all. How long and complicated everything that I have written over the last three years has become, and how short and sweet and highly casual things were in the earliest days of this site. At 700 words today, I’m, like, not even out of the introduction and haven’t even started to talk about the album I’m supposed to be writing about.

2- This is just a quick aside of frustration to talk about how cute it is that, only four years ago, in the very early stages of “peak vinyl,” an album could be digitally rushed into release, like Daytona was, then there was only a two or three-month turnaround on the LP’s arrival, rather than the six to seven-month wait there is now, especially for smaller artists who are getting bumped from their place in production plants thanks to major labels muscling their artists in.

3- I had intended to come back to the anecdote I opened with, about my former co-worker, but the further I got into this piece, the more challenging it became to fit that story back in. The story concludes with me handing her my copy of Daytona on vinyl as a gift, mostly because I found I hadn’t listened to it in two years and wanted it to go to a good home. Because young people do not spend as much time laboring over cover art and liner notes the way someone pushing 40 (like myself) does, she glared at the cover art to Daytona (famously Whitney Houston’s drug littered hotel room vanity) and had no idea what it was. I, again, had to explain, “It’s Daytona? From Pusha T? You told me you really liked this?”

4- I think my intent, at least early on in writing this before it all kind of got away from me and became about more than just the album itself, was to talk about how “Brambleton” tells the story of Pusha T’s falling out with his former manager. There’s a lot of information online about the mythology around it if you are interested.

5- How many people listening to this album will understand the reference to the Amblin logo—Steven Spielberg’s production company that features the bicycle-riding children from E.T. in it?

6- “Top five and all of them Dylan,” from “What Would Meek Do?,” is a reference to the “Making The Band” skit featuring Dave Chappelle playing three characters.

7- I felt like I had wanted to mention this lyric at some point but, initially, had forgotten and was uncertain how to write it back in. There is a reference to the Temptations’ vocalist David Ruffin that, again, like the Amblin logo, is extremely specific and operating on a level of cleverness that I am not sure how many listeners will connect with, but I at least appreciated it.

8- East Coast from the early to mid-1990s.

9- I had given serious consideration to writing about the new Billy Woods album released earlier in April. Still, as a lyricist, Woods is so intelligent and complex that the more I listened to the album, I became intimidated even to touch it. Also, I am often too overwhelmed by the amount of music I want to write about versus the amount I actually can write about; and am usually too depressed to do any of it with any efficiency.