What's The Worst That Could Happen? - My "Favorite" Albums of 2021

Not counting the piece about my favorite songs of the year—I apparently made 43 posts on this site in 2021. And out of that 43, unless my math is incorrect (which would not be surprising), at year’s end, I guess I wrote about 24 albums released this year.

That doesn’t mean I only listened to 24 albums released in 2021—that means I just made the time, effort, space—whatever, to really sit down with an album and give it a lot of thought before putting my fingers to the keyboard.

For every album I do end up writing about—there are countless others I would love to dedicate all that time, effort, and space to, but am unable to.

At my lowest point, with these end of the year lists, I could only name seven albums. This would have been in 2015—a difficult year for me personally, and by December, with how much emotional baggage I had been carrying around, I was more or less mailing it in with the writing, and how much thought I was putting into the writing, with the site.

Looking at previous lists of what I would call my favorite records of any certain year is a fascinating exercise in terms of looking at how my tastes have shifted—what albums, say, from the earliest days of this site do I still return to with any kind of regularity? What albums that, at one time, I deemed to be the very best of a given year, have just sat on my shelf, gathering dust?

What albums to I, in retrospect, regret including?

I always want these to be two things within the same time, and I am uncertain if that can ever really be the case. You want it to be timeless—or, at least, mostly timeless. You want to look back on a list, not wince at the choices you made, and still feel that connection to a particular album.

Within the same breath, these are representative of a moment—a time, just 12 months. And tastes change. Opinions change. And it is, at the end of the day, completely okay that something I felt very strongly about in, say, 2018, is an album I literally never revisited in subsequent years.

Similarly, as with the list of my favorite tunes of the year, I took some liberties here when revisiting an enormous stack of albums, then slowly selecting which ones I would place on this list.

There are 16 separate releases here—two of which are ranked within the same line item, and three of which were, for whatever reasons, the “best” of the best—the ones that had the most emotional impact on me, or that I found myself returning to more than anything else.

Anika Pyle - Wild River

(originally reviewed May 27th)

A number of months ago, I was having a conversation with a close friend, and in it, she said something that has really stuck with me, and probably will for quite a while—“I wish my life didn’t feel so small.”

There was an urgency to the way she said it, and a longing—the kind of longing that I, to the extent that I am able to, understood. The kind of wish, or desire, or whatever, for something bigger—not bigger than ourselves—no, but to live a life that was larger than, and where we were not constantly humbled by, our anxieties and fears.

And when she said this, it reminded me of the final line of the titular song on Anika Pyle’s debut full-length under her own name—Wild River.

“I wanted to be a wild river, but I’m still a country creek.”

Writing about Wild River now, at year’s end, isn’t any easier, because all of those things it brought up for me are still there—I never anticipated any resolution with them or for them.

A collection of both reflective, emotionally charged songs, woven together with a series of spoken word poetry, Wild River is, putting it mildly, extremely emotional. It’s not an easy listen; but here’s the thing—not every song, or album, always needs to be easy to sit with, or a readily accessible listen.

Partially a product of the solitude Pyle found herself in during 2020, Wild River is not easy simply because of what she unflinchingly writes about, and in turn, uses the album as a means of trying to process as best as one can—grief, both for the death of the father she had almost a lifelong estrangement from, and for her paternal grandmother—as well as a harrowing, at times bleak exploration and confrontation with one’s self—the depression we may be alway attempting to outrun, or the effacing ways we may view our own shortcomings.

“Everybody is a failer,” Pyle says at one point on the record, as a reminder both to the listener and herself. “Nobody is a failure.”

Musically a departure from Pyle’s work fronting the pop-punk outfits Chumped and the extremely excellent and poignant Katie Ellen, the instrumentation on Wild River, across its eight songs, are best described as lo-fi in aesthetic, pulling together elements of acoustic-centered folk, alongside dusty and antiquated sounding drum machine programming, and twinkling, at times a little whimsical sounding, keyboards—the result creates a sense of home recorded intimacy, lending itself to the extremely personal, confessional nature of Pyle’s songwriting and poetry.

It should not be surprising that it is Pyle’s lyricism that ends up being the most difficult (emotionally speaking) element to Wild River—simply because how much of myself I saw within her words, and the kind of long gestating, complicated feelings that these songs, and the conceit of the album as a whole, brought up for me, because of the way, for nearly a decade, I have found myself more or less unable to process grief.

“Grief is a grasping for the little things,” Pyle says on the spoken word piece about the last time she saw her father before his passing. “In the end, they are the only things—everything.”

It’s Pyle’s lyricism that ends up being the most difficult (emotionally speaking) element to Wild River simply because through her tender depiction of the long fractured, then carefully mended relationship with her father, it brought up for me the long fractured, practically non-existent relationship I have with my own father.

It’s Pyle’s lyricism, and the way she is, throughout the album, very frank about her own grappling with “successes” and “failures,” and the darkness that she, like many of us, are always trying to stay a few steps ahead of. “Dreading the moment when you inquire how the past few months have been,” she sings underneath a quickly strummed acoustic guitar on “Blame.” “At the mirror practicing how to trade a little fear for confidence…I’d say I was making do, ‘cause. Most of the time that feels like truth.”

“Another day to wish there were no more days here—somehow hold on,” she sings, somberly, honestly, on the album’s devastating centerpiece, “Haiku for Everything You Love and Miss.”

I think of my friend, and her desire for a life that isn’t deemed to be so small—and my own desire for that, too, and how much of myself I see reflected in the lyrics to “Wild River,” as Pyle lets them tumble, then soar, against the swooning and swaying arrangement—

I like to clean the kitchen at parties

I like to stay in on the weekends

I thought I’d be something special but chasing my dreams always made me a little too anxious

And I never flirted with danger

In fact, I have an arranged marriage with the meticulous routine

Of rising each day before six o’clock in the morning

And I wanted to be a wild river, but I’m a still country creek.

For a number of years now, I have been chasing this place where both grief and joy can co-exist, and I am uncertain, even after this long, if I will ever get there. Maybe because I don’t know where it is, or how to get there—or maybe it is because, even in all the discomfort, I remain where I am because it is what I know—forgoing the fleeting the joy as it escapes my grasp, and continuing to slowly drown in grief.

There is a place here both grief and joy can co-exist, and an album like Wild River, even in the chaos and confusion it can cause when those two things intersect, is the sound of someone trying to find the balance between the two—an absolutely unforgettable album that cuts to the core of the human condition.

Sydney Sprague - Maybe I Will See You at The End of The World

(originally reviewed March 25th)

How difficult must it be to walk the line between making music that is an absolute blast to listen to, time and time again, full of enormous, memorable hooks that compel you to shout along—and making music that simmers and boils over with emotional, thoughtful lyrics that, time and time again, shake you to your absolute core?

If you are singer and songwriter Sydney Sprague, regardless of how difficult it might be, you make it look effortless.

At first glance, Sprague seemingly came out of nowhere—though the more I sat with her blistering, jaw dropping debut at the first part of this year, Maybe I Will See You at The End of The World, and the more I read up about her, I realized that wasn’t exactly the case. Self-releasing a series of of now literally impossible to find EPs during the first part of her career as an up and coming performer in the Phoenix, Arizona area, Sprague earned a living and built her skills playing countless gigs singing cover songs. Heading into the studio to lay down Maybe I Will See You at the start of 2020, when the country was just on the cusp of the pandemic, the nervy tensions and anxieties present in her lyrics were, at the time, just her own.

But, a calendar year later, upon the album’s release and another year into a state of heightened emergency that seems like it never going to fucking end, those tensions and anxieties mirrored our own in myriad ways.

One might think, if you spent enough time listening to, or immersing yourself in a specific song, or artist, or album, you might grow weary of it after so many months—that is simply not the case with Sprague or Maybe I Will See You. From the moment the needle hits the record, I still feel an electrifying thrill from the ferocious opening guitar chords of the song’s audacious opening track, “I Refuse to Die.” The title itself a bold statement, and the song is performed with a visceral immediacy—but the expression itself, or the very idea of refusing to die, is playing against type for Sprague, which is something you figure out the further you get into the album.

Yes, the exuberance of songs like “I Refuse to Die” and the bombastic “Steve” are among the album’s most fun, but it’s in Maybe I Will See You’s most quiet, or pensive moments, where the personal gravity of Sprague’s songwriting is the most prevalent—like the slightly twangy, slow burning “Quitter,” where there is a tangible sense of regret and yearning in the chorus—“Did I pass you by somewhere on Freeway last night,” she asks. “Did you see me screaming out the window, ‘bout to lose my mind? Would it be alright if we gave it another try?”

Or on the dizzying, cathartic closing track, “End of The World,” while flanked by heavy atmospherics, Sprague confronts both the ideas of loss and her own mental health—“I don’t know what’s going on with me lately—I just think the worst, and my body’s breaking down,” she confesses in the first verse, before conceding in the end with no true resolution, “Replies are all rehearsed now, so when I say I’m doing just fine—finding different ways to pass the time. Maybe I will see you at the end of the world.”

And there is a place—perhaps it is surprising, and perhaps it isn’t—where these two distinct elements from Maybe I Will See You converge. Opening the album’s second half is the rollicking “Staircase Failure,” which is built around an unrelenting clattering rhythm, an unhinged and infectious guitar riff, and an undeniable groove, all of which creates the foundation for some of the most indelible lyrics—like the attention grabbing opening line: “I’m descending into hell; it’s the way you fuck my head up,” or the scathing observations in the second verse—“I just focus on my friends; it’s the way they walk in circles. They’re a seven out of 10 on a scale of being difficult.”

In my initial piece on Maybe I Will See You at The End of The World, I felt that Sprague’s brazen refusal to die was the “mission statement” of the album, but now that I have had, like, nine more months to sit with this album, what I’ve realize if there is a thesis, or a central conceit to it, it’s the question she returns to as the chorus in “Staircase Failure”—the question that is never answered, as their is never a real resolve at the album’s end—“What’s the worst that could happen?”

What is the worst that could happen—in a week? A month? Within a year?

And maybe we don’t want an answer, because maybe we know that there is always going to be something.

There is always going to be something, and we keep going, though, don’t we? We keep finding our own means of refusal—whatever that might look like for both you and me. If there was one album that could be a soundtrack for 2021, it would be Maybe I Will See You at The End of The World, with Sprague finding where you can feel those fleeting moments of joy, the agony of breaking down once more, and spaces that gradually form in between those two extremes.

The Staves - Good Woman

For every album that I wind up sitting down with and opting to write a piece on for the site, in many instances, throughout the year, for myriad reasons, that I am simply unable to.

And at year’s end, reflecting on Good Woman, the gorgeous, infectious, dizzying, and at times, surprisingly fun fourth album from the UK trio The Staves, what I cannot recall is first, how I initially was introduced to the group, and this album; and secondly, why—even when it was included, for some number of weeks, on my “albums to write a piece on” list, I opted not to, and chose just to enjoy it throughout the year without immersing myself in the critical thinking process about it.

If I had to guess, based on when Good Woman was released—the first week of February, and based on when I had made the decision to order a copy of the LP—the second week of February—to say that this not a “good time” for me in 2021 is an understatement, in terms of stress in the workplace, my failing mental health, and caring for an ill family member.

I have this thing—maybe it’s a “problem,” or maybe it’s just the way my brain works, but I have this thing where I am often unable to sever a connection between when an album was released, or when I heard an album for the first time, with what was happening in my life. And because of this, I live with a lot of wistfulness I may otherwise not; it doesn’t always happen this way, but because of this, my feelings about certain albums—or even certain artists—have soured, simply because when I think of them, or of the specific album in question, it takes me back to a moment I may otherwise not want to return to.

Somehow, though, at year’s end, I did not make that kind of connection with Good Woman. It remains an album that I was first introduced to during the chill of February that I, from beginning to end, absolutely adore. Rarely am I willing to be so bold as to declare an album “perfect” or “flawless.” Often, there will be, like, one or two songs that don’t land for me and I’ll be like, “this album is damn near perfect.” The thing about Good Woman is it isn’t near perfect.

It simply is. A perfect, beautiful album from start to finish.

A literal family band, The Staves is primarily made up of three sisters, and if you have any doubt about their vocal prowess or ability to harmonize being some kind of product of studio trickery or post-production work, please watch their somewhat recently recorded NPR “Tiny Desk” concert, where the three sisters, Camilla, Emily, and Jessica, perform in the small kitchen of their family home—even in a stripped down setting, lacking some of the additional bombast Good Woman is constructed around, the way their voices converge together in harmony is fucking astounding.

It would be easy to call The Staves an “indie folk” outfit because of their adoption of intricate vocal arrangements and gentle, acoustic instrumentation. Good Woman, though, is a place where those kind of organic, hushed, folksy sounds collide with swooning flourishes of wind and string instruments, warm twinkling synthesizers, and even dissonant noise loops—the the squalling sample that opens the album’s third track, “Careful, Kid.”

The inclusion of orchestral accompaniments adds a layer of depth, yes, but the addition of electronic elements, in any form, can feel shoehorned in and out of place, but that never happens on Good Woman—The Staves create just the right amount of friction between the components to keep each song rich and compelling.

Within all that texture—rich, warm, dense at times—the sisters have a knack for pop sensibilities and accessibility in their songwriting. The layers of their harmony vocals keep things gorgeous and interesting, but its the infectiousness of their melodies and enormous choruses that make Good Woman such an accomplishment in terms of a flawless album. Even songs that simmer with tension, like the opening, titular track, can get stuck in your head, but it’s the really big moments that are the most impressionable—the frenetic urgency of “Best Friend,” or, the swirling, sweeping “Next Year, Next Time,” and even as deprecating as it is, the bombastic groove of “Failure.”

Finding the space between something delicate and something with just a little bit of an edge, or a snarl to it, Good Woman, while managing to maintain a slight sense of humor throughout, is a stunning, introspective experience of a record—the kind of album that, through repeated listens, becomes like a long conversation and warm embrace from your closest friend.

* * *

Adult Mom - Driver

The complete irony of the band name, Adult Mom, isn’t lost on me, though I have to admit that it took a little bit, following the release of Driver, for it to really sink in. But what didn’t take a while—in fact, what was obvious from the very beginning, are the surprising contrasts that bandleader Stevie Knipe makes throughout—primarily in their lyrics.

Almost right out of the gate, there are moments on Driver that are more wholesome or charming than expected—“Last night, our knees kissed on the couch of your parent’s basement,” Knipe muses vividly on the album’s second track, “Wisconsin.” “Your arm brushed mine as you reaching over me to grab your water—what does it mean?,” they continue. “Do you want me?”

Knipe then, only a few songs later, contrasts that with the depiction of something far less endearing. “The only thing that I’ve done with month is drink beer, masturbate, and ignore phone calls from you—what else am I supposed to do?,” they ask on “Sober.”

That, then, could be contrasted with the inherently harrowing, effacing lyrics from the album’s slow burning opening track, “Passenger”—“I was a passenger in your car, and now I’m a ghost who won’t answer a call.”

Musically, Driver, Knipe’s third full-length under the Adult Mom name, is an enormous leap forward for the project in terms of the scope and focus with regards to the instrumentation, arranging, and tone. Driver isn’t Adult Mom’s “pop” album, but there is a surprising infectiousness to the way a lot of these songs are executed—something that may not have been as apparent, or present, in past efforts—there’s an apparent bombast in the big, strummy electric guitar chords and rolling percussion on “Wisconsin” that gives it an undeniable groove; the same can be said for “Breathing,” which begins with a chintzy sounding keyboard and drum machine before reaching heights that shimmer, or the slithering, albeit melancholic rhythm of “Berlin,” and the way Knipe mesmerizes with the repetition of the line, “Sit in the car parked in the dark hearing drain drops on the roof.”

And what I have realized the more I have sat with Driver—wading past just how bright and big it can sound, is that, lyrically, it’s an album about fractures. At the core are Knipe’s unflinching depictions of a fractured relationship—“You are the one I think of when I think about the things I’ve done wrong before,” they confess late in the album on “Checking Up.” “You are the one I Think of when I Think bout the things that I’ve fucked up before in my life.”

But it’s also about a fracture within the self, and the difficulties that come from both sitting with that, and trying to navigate your way back.

The self-deprecation present throughout Driver is enough, once you recognize it is there, and perhaps, see a little too much of yourself in parts of it, to knock the wind out of you. “I am nothing special,” Knipe quips on “Breathing.” “Just an emotional vessel. So covers up—hide myself.”

Or in the jaunty “Adam,” in the album’s second half, “I think bout making lists of how I’m shit—god I can be so relentless.”

There are no easy answers, or a clear resolve, by the time Driver ends, though Knipe’s final line is an acknowledgment of the kind of work that needs to be done, regardless of how challenging or insurmountable it might seem at times—“I’m aware I might be too good at being alone. I might be too good at closing myself off. No one can let me out but myself.”

As “fun” or lively of an album as it might sound at times, as it is just as audacious and poignant, of not more so, in how it becomes a mirror that we might catch a difficult reflection of ourselves in.

Arooj Aftab - Vulture Prince

This would have been a few months after the release of Vulture Prince, when my copy of the extremely difficult to come by vinyl edition of the album arrived in the mail, and a friend of mine—she had, originally, introduced me to the record shortly after it came out in April—asked if I was going to write a piece on it.

And as much as I would have liked to sit down with the album at any point in the spring, and into the summer, listen to it analytically, and attempt to gather my thoughts—I knew that it really wasn’t an option. There are, of course, a number of reasons why it wasn’t—but the most obvious to me, at the time, was that Vulture Prince is entirely too intimidating of a record to write about in the way that I find myself most often writing about music.

And however intimidating that might have been—and still is, months later, it didn’t prevent me from what I find that I am sometimes unable to do, or at least have a real difficulty doing—and that is simply listening and enjoying; and in the case of Vulture Prince, listening, enjoying, and regularly being moved by the haunting, otherworldly beauty it holds within.

It was the language, in the end, that I saw as a barrier to being able to accurately write about Vulture Prince—or, at least, was the element to the album that I found the most intimidating. Sung almost entirely in Hindustani, there is certainly a feeling that Arooj Aftab’s voice creates—the feeling is one thing, yes, and perhaps I could have written about that, but I believed there there was only so much I could say about an album when I was unable to write about the album’s lyrics with the accuracy that I wanted to.

Vulture Prince, at its core, is a meditation on loss—Aftab was in the process of writing for the album when her younger brother passed away. His death, as well as his memory, serve as the inspiration for the direction the album then took. And because of this, Vulture Prince often operates within the unlikely and shared space between grief and joy—the gorgeousness and the dissonance of it all creating a kind of emotionally charged give and take, with Aftab in the center, trying to find the right balance of each emotion.

It would be insensitive, or ignorant of me to refer to Vulture Prince as “world music”; this collection of songs is truly unlike anything else I encountered this year, and is utterly defiant in its ability to resist a clear genre, or style. Are there elements of jazz and folk? Sure. Does it pull from what the Pitchfork review called “South Asian blues”? Probably. Is it steeped in Hindustani classical? Of course. But there is a transcendental nature to Vulture Prince—found within the way Aftab controls and commands her voice like an instrument, and the unnerving tension that many of the songs have woven into their delicate, complicated arrangements, that make it not just a wholly unique album, but a listening experience. From the hypnotic, swirling acoustic guitar string plucking of “Mohabbat,” the glistening, intricate harp playing and calming reassurance set in the stunning opening piece, “Baghon Main,” to the long ripples of effected, mournful electric that cascade throughout the devastating “Saans Lo,” Vulture Prince is a definitive artistic statement for Aftab—the kind of album that demands your attention, and once you are listening, it never truly lets go.

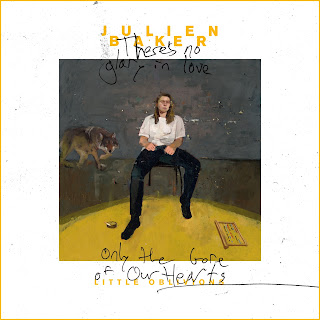

Julien Baker - Little Oblivions

(originally reviewed March 4th)

“What if it isn’t black and white—what if it’s all black, baby, all the time?”

On her third full-length, Julien Baker poses this question near the end of album’s opening track, “Hardline,” and, in a sense, it’s a question, or conceit, that Baker traces throughout the entirety of Little Oblivions—and it’s a question that, at the album’s conclusion, she’s never truly able to find the answer.

What if it’s all black, baby, all the time?

Little Oblivions is a lot of things—notably, it is Baker’s first foray into building songs around additional instrumentation and full-band arrangements; you could hear her flirting with atmospheric flourishes on stand alone singles like “Red Door” and “Tokyo” in 2019, but here, any kind of restraint she was showing in the development of a larger, more robust soundscape is long gone.

Like Sprained Ankle and Turn Out The Lights before it, Little Oblivions is extremely personal, with Baker continuing to question her identity and spirituality, but this time around, she is also desperately seeking a kind of redemption and forgiveness that continues to escape her grasp. Baker has been relatively upfront about her substance use of the past and subsequent sobriety—something that, throughout this collection of songs, she chronicles struggling to regain after losing it.

Musically, Little Oblivions is an absolute marvel simply for the way that, over the course of her career, she has been able to slowly ease herself into crafting songs that are arranged in this way—at no point does it come off as alienating towards fans who might favor her earlier, sparser material. It’s a surprise at times, yes, but it never comes off as a total shock, or like something that just isn’t going to work.

Lyrically, the word “bleak” undersells just how fucking dark Little Oblivions is. And what I realized when sitting down with the album upon its release is just how much violence Baker depicts in her songs—this album is no exception. But outside of the acts of physical violence she writes of, it is the emotional violence that resonates the deepest, and perhaps, is the most difficult to hear. “Start asking for forgiveness in advance for all the future things I will destroy,” she utters in a low voice on the bombastic opening track, “Hardline.” “That way I can ruin everything and when I do, you don’t get to be surprised.”

Or, in the album’s second half, on “Ringside”—“Nobody deserves a second chance, but honey, I keep giving them.”

And it is the question in “Hardline” that I found myself returning to most in 2021—it was the question that hit me the hardest the first time I really heard it. And it was the question that, even with Baker being unable to find an answer, I understood it.

In turn, I felt like the question, itself, understood me.

What if it isn’t black and white?

What if it’s all black, all the time?

Lucy Dacus - Home Video

(originally reviewed July 1st)

There is this Instagram page I follow—Poetry Is Not A Luxury—and somewhat recently, my best friend shared a post from it: “The past beats inside me like a second heart.” The quote itself is attributed to John Banville, and it is also used as an epitaph in the book Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir, by Natasha Tretheway.

The quote itself, as one might expect, had me feeling some type of way—and the more I ruminated on it, and how accurately it depicts my own relationship to the past, I found it to be an accurate way to describe Home Video.

Home Video isn’t a “difficult” album—it’s often as wildly infectious and accessible as it is bold and surprising in the way Lucy Dacus has pushed herself and grown as a songwriter and artist; it is, however, an album about difficult things, specifically Dacus’ relationship to her own past, like the slow acknowledgment of her queer identity, or her extremely religious upbringing.

Dacus explores these facets of herself as gracefully as one can, and in doing so, immerses her listeners in a fully developed world comprised of characters pulled from her own life—like the questionable romantic partners from her teenage years, as depicted in “V.B.S,” “Hot and Heavy,” or “First Time,” where she sings the surprisingly frank double entendre, “I may let you see me on my knees but you’ll never see me on all fours”; or ruminating on the development of friendships with both the opposite sex (unflinchingly and awkwardly detailed in “Brando”) as well as with other girls—the tender concern of “Christine,” the scorn and jealousy of “Cartwheel,” and the album’s unforgettable centerpiece, “Thumbs.”

More or less front loaded with what I would hesitate to call “the hits,” but what I would refer to as its most energetically executed songs, Dacus stores the most compelling—musically and lyrically—and most emotionally resonant for the second half of Home Video. Through the unexpected use of Auto Tune on her voice, and a slinking (though somber) R&B groove in the arrangement, she revisits having lied about her age to enter into a troubling relationship with a much older man on “Partner in Crime”; or, as she is joined by her boygenius bandmates Phoebe Bridgers and Julien Baker, recounts a role she says she has played “throughout” her life of attempting to convince a loved one life is worth living on the heartbreaking, sparse “Please Stay.”

If “Thumbs” is among the most remarkable and memorable songs included on Home Video, the album’s sprawling closing track, “Triple Dog Dare” is right there alongside it. A slow burning narrative where Dacus recalls the realization of romantic feelings for a close female friend from her youth—she does so with meticulous, poetic detail within the first verse of the song: “You’re dancing in the aisle ‘cause the radio is singing as song you know,” she sings. “And the kid at the counter is gawking at your grace. I can tell what he’s thinking by the look on his face. It’s not his fault—I’m sure I look the same.”

“Triple Dog Dare,” beginning as a near whisper, continues to grow to surprisingly cacophonic heights as Dacus recounts more of the narrative—she is, eventually, forbidden to see her friend after a palm reading reveals her secret (“I never touched you how I wanted to—what can I say to your mom to let you come outside?”), and in the end, there is no real resolution—just two, young and frightened teenage girls grappling with what their feelings might mean. “Triple Dog Dare” detonates through the hypnotic repetition of its titular phrase, and after beginning its descent, serving as a bit of an epilogue, the final verse is where Dacus has the chance not to re-write her own story, but to pause and imagine a “what if” scenario where she and her friend ran off together—“Missing children ’til they gave up,” she says, before concluding with something that, for me, took on a much larger meaning within the scope of what I have lived through and lived with this year, and have thought about literally every day since hearing it for the first time, months ago—

Through the grief, can’t fight the feeling of relief—Nothing worse could happen now.

Nothing worse could happen now.

Flock of Dimes - Head of Roses

In terms of fleeing jokes on the internet (i.e. Twitter) I am uncertain how long this actually lasted, or what kind of impact it might have had, but there was a moment earlier this year where the expression “I contain multitudes” was being used—kind of in an aggressive or confrontational way when communicating two relatively contrasting things about yourself.

It made enough of an impression on me, at least in the spring, because I found myself discussing the “multitudinous nature” of specific albums I was writing about at the time—and Jenn Wasner’s second full-length under her Flock of Dimes moniker was one of them.

One of Wasner’s outlets outside of her work as the vocalist and multi-instrumentalist in the long running duo Wye Oak, she launched Flock of Dimes a decade ago with a one-off single included on a complication cassette of other Baltimore based artists. Then very glitchy and spiraling, her sound as Flock of Dimes has matured and evolved over the last ten years, in a sense, taking on whatever shape and sound it needed to in that moment.

Head of Roses, like a lot of records I spent time with this year, is more than what it appears on its surface—is it an album recorded during quarantine, with a carefully selected stable of collaborators? Yes. Is it a collection of songs written in the solitude Wasner found herself in following the breakup of a long term relationship, shortly before the pandemic hit in March of 2020? Also, yes. The heart of Head of Roses, though, is about how—if at all—can you be two versions of yourself? How can you find the balance between your “self,” and who you are in terms of a relationship you are in?

Or is there even a balance one can strike?

Those kind of questions are found in songs like the rollicking and jubilant first single from Head of Roses, “Two,” which aptly asks in its chorus—“Can I be one? Can we be two? Can I still be for myself? Still be with you?”

Even when it is, fleetingly, jaunty, or even when it is at is most raucous and smoldering—the album’s sprawling, noisy second track, “Price of Blue” features surprisingly searing electric guitar work throughout—Head of Roses, and perhaps its the nature with which it was conceived, is a very insular record, with many of the album’s arrangements, often hushed or gentle, matching Wasner’s pensive, and at times, extremely harsh evaluations of both the end of the relationship that inspired Head of Roses, as well as the very notion of “the self”—“And I deserve it, the very worst of it,” she sings somberly on the album’s finest moment (and one of the most emotionally impactful songs of the year) “Awake For The Sunrise.”

With extraordinarily personal albums such as this, there is often no clear resolution for the artist as the record comes to an end. Wasner closes Head of Roses with the stunning, piano accompanied titular track, and in it, she finds the most solace that she is able—“You’ll never see how I cried…leave me to learn—love is time.”

Representative of a very specific moment in time for Wasner, and used as a vessel for emotional release, Head of Roses is a beautiful statement on the human condition, and an album that even as someone else is using it to see unflattering reflections of themselves, you are able to catch glimpses of yourself, as difficult as it might be to see, in it as well.

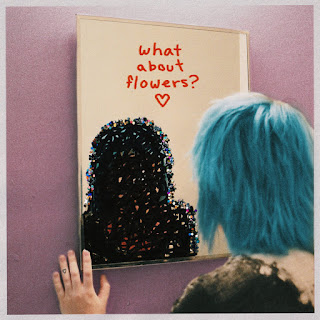

Future Teens - Deliberately Alive EP/Snarls - What About Flowers? EP

(Future Teens reviewed originally on April 15th)

There are times with these end of the year lists—my “favorite” songs or the year, or albums—where I inventively find myself taking a few liberties when it all tumbles together at the end. And I suppose this is one of those occasions.

Did I place extended plays by Future Teens and Snarls on the same line item because they were both issued by the label Take This To Heart? Perhaps.

Did I put Deliberately Alive and What About Flowers? together because they both contain five songs each? Arguably adding up to the length of a “standard” album? Yeah. Maybe.

Did I do this because, anecdotally, or subjectively speaking, both of these bands operate within similar genres, or at the very least, share some similarities in sound?

I guess. I don’t know. This one is a little bit of a stretch.

It’s difficult for me to think of a band in recent memory exhibiting as much promise as Snarls did on Burst. Released last spring—a challenging time for any artist to release an album, let alone a debut full-length. Now returning with this collection of five new songs, produce by former Death Cab For Cutie guitarist Chris Walla, the Ohio four-piece has doubled down on their strengths with the material included on What About Flowers?.

Operating in a space that is created when “alternative rock,” shoegaze, dream pop, and emo all intersect—an amalgamation of genres that in less capable hands, might sound like an absolute disaster; Snarls, however, are preternaturally confident in their ability to blend their influences seamlessly, shooting their shots across this EP, and never missing. The enormous, sing along hooks that made Burst such an absolute joy are in tact, and perhaps, even more enormous this time around, like the absolutely soaring chorus of the opening track, “Fixed Gear.”

The group had also displayed on Burst that they can do downcast extremely well—that tone also returns across What About Flower?, perhaps most powerfully on “For You,” which sounds like a slow motion torrential downpour of distorted, distended guitars, while the group’s vocalist, Chlo White allows her voice to howl with a wounded otherworldliness.

*

At year’s end, what I cannot recall is how many listens it took for the weight of the second track on Deliberately Alive, “Guest Room,” to register—but I remember the moment when it did, when I was on a walk home from work, and I really heard, and understood, the lyrics that Future Teens’s vocalist Amy Hoffman was singing.

“I’m not sure which one I fear worse—going young, or getting old. I guess I’ll take whatever comes first. It’s not like I had a say in being born; at least I’m not convinced I deserve either one anymore.”

Running a spry 16 minutes, across five songs, Deliberately Alive begins with with a song about the challenges of being honest with yourself and others about your mental health, ends with a smoldering cover of Cher’s iconic “Believe,” and covers myriad emotions (highs and lows) in between.

In my original piece on Deliberately Alive, I found the easiest way, and most subjectively accurate way, to describe Future Teens was as “emo music for adults”—the kind of band making music that might most resonate folks who are in their mid to late 30s, still kind of attached to their copies of, say, Jimmy Eat World’s Clarity, and are an emotional mess most of the time, but are really trying to work on themselves. And it’s those efforts at not so much “self improvement,” but of a better understanding of one’s self that Hoffman and Future Teens founder Daniel Radin focus on throughout the effort.

“I think this is broken and it won’t end ‘till someone says something they actually mean,” Radin begins in the opening of the jittery, shimmery “Play Cool,” and somehow manages to maintain his sense of humor about it all—as macabre as it might be, with the next lines. “Crying outside the venue aptly named where I fell to—at the bottom, once again.”

Trading who takes the lead, it is Hoffman’s voice again on “Bizarre Affection,” and they are even more brutal and effacing in self assessment.

“I tried to forget about that night on the lower east when I cried at the bar while you gave me your answer,” they sing against a melancholy arrangement. “I think I get it now—god damn, I was selfish. There can’t be anyone else until there’s no you.”

There are no easy answers on Deliberately Alive—just the indication of the emotional heavy lifting that needs to be done, however difficult it might seem.

With both Deliberately Alive and What About Flowers?, Future Teens and Snarls show they are able to compress enough compelling, thoughtful, and visceral emotion into five songs each, while other acts, or artists, may not even be able to do the same across the canvas of a double album.

Jodi - Blue Heron

(originally reviewed on August 16th)

“Am I coming down with something, or just coming down?”

And that’s the thing about Nick Levine’s full-length debut under their Jodi moniker, Blue Heron—the contrast that is created between the fragility in their voice, the gentle, often delicate yet lush folk-tinged instrumentation, and utterly breathtaking, stark, ambiguous lyrics such as that—giving you a lot to ruminate on in the album’s wake.

With a vocal range that, at times, shares a handful of similarities with the late Jason Molina, and primarily acoustic in focus arrangements that are akin to Mark Kozelek’s Sun Kil Moon, circa 2005 to 2008, what makes Blue Heron such a phenomenal record from this year is the way Levine plays with balance between the gorgeous and sweeping moments written into the music—e.g. “Go Slowly,” and the beautiful, swooning sense of drama, or in the jittery, shuffling, borderline whimsical, and swirling grandeur of “Hawks—with their fragmented, thoughtful, and at times, surprisingly dark lyricism.

“Am I coming down with something, or just coming down,” Levine casually, quietly asks in the opening line to the closing (and titular) track on Blue Heron. Set against a ramshackle drum machine rhythm and a mournful acoustic guitar, they continue in the song’s second verse, “Trying to find a place to meet friends but they’re all closing down. But, is it really so bad to be floating around? Come on, Jodi. Get it right—work it out. Don’t let me down.”

And it’s that sense of yearning—at times desperate, and a palpable loneliness, that Levine returns to throughout Blue Heron’s lyrics, often in just a line here or there, uttered and then never really elaborated on further, like on the dissonant, trudging “Slug Night”—“Sober up, you wandered out to find a friend but everyone is closing up or closing down,” or in the devastating tumble, “Softly,” where they ask the question, “Where’s your faith in me?,” but they never receive an answer.

Extraordinarily intimate and rich in the way it was co-produced and mixed by both Levine and Tommy Read (the precision and detail in the way it sounds make it essential headphone listening), it is truly Levine’s poetic, vivid use of language that make Blue Heron an album that doesn’t so much linger with you once the record has ceased spinning—it haunts.

Kississippi - Mood Ring

(Originally reviewed on September 1st)

I think I had kind of surmised this during all of my time spend listening to Mood Ring shortly after it was released digitally, and while I waited for my slightly delayed LP to arrive—but in revisiting it at the end of 2021 to confirm my adoration for it, what I have truly come to understand is that Mood Ring isn’t exactly a “concept album,” because its songs can exist outside of the context of the album as a whole, but it is, however, a loosely connected cycle of songs that appear to track the rise and fall of a relationship.

On her second full-length under the Kississippi moniker, Zoe Reynolds sheds a bulk of the guitar-leaning “indie rock” sound of her debut LP, Sunset Blush, and with open arms, embraces gossamer and glossy, synth heavy, 1980s pop-inspired sounds—an aesthetic (a very far cry from the project’s moody beginnings from, like, five or six years earlier) that is perhaps temporary for Reynolds and her band, but is simply the best and most appropriate pallet for the kind of material found on Mood Ring.

Opening with the flirtatious “We’re So in Tune” and “Moon Over,” before heading into the lustier territory of pop music love songs—less overtly horny than, say, anything off of Positions by Ariana Grande, Reynolds leaves little to the imagination with lyrics like, “Show me the green light…you can choose honey, tell me what you like,” she coos and swoons on “Heaven.” “Can you take me naturally—baby it feels so right.”

These songs are fun, yes, and often built around enormous sing along chorus and instrumentation that absolutely dazzles; but it is the material written about the relationship’s difficult demise that is the strongest, or most impressive, on Mood Ring, like the theatricality of the closing track, “Hellbeing,” where Reynolds still pines—“If I wasn’t so selfish, do you think we could be friends, like back when you were the best?” Or, the penultimate track, and one of my favorite songs of 2021, “Big Dipper,” slow burning and shimmering, and including a single lyric that will stay with me long after this year is over—“I know it ain’t easy to love me.”

Rarely can an album juggle such bright arrangements with such thoughtful, albeit at times a little saccharine, lyrics, but Reynolds strikes an impeccable balance for those in love, those in lust, and those with a broken heart, and makes space for them all to get lost in the darkness on a dance floor.

Lady Dan - I am The Prophet

(originally reviewed on May 17th)

A restlessness.

That was one of the ways that I described Tyler Dozier’s full length debut as Lady Dan, I am The Prophet, when I first encountered the album around the time of its release this spring, and it’s the word I returned to at year’s end, when reflecting on what it was that made it such a memorable listen. From the moment it begins, all the way through to the thrilling, stunning final song, Dozier writes and sings from a place of refusal, or an unwillingness to settle—musically, yes, but personally as well, which is why I am The Prophet remains such a captivating, intelligent collection.

Dozier, across the album, is whip smart in her lyricism—any songwriter bold enough to use the word “misandrist” in a song title would have to be. “I’ll be my own savior; I’ll be my own best man,” she bellows on the rollicking, heavily percussive “Misandrist to Most,” and almost across the entirety of I am The Prophet, Dozier is both subtle while remaining absolutely scathing in the way she deploys her sense of humor, and the way she takes aim at her targets—men, specifically, from her past, whether it be bad boyfriends, or the pastors she encountered in her extremely religious upbringing that she has since escaped.

“I’ve got a new skin,” she howls on the gorgeous and expansive “No Home,” which begins the album’s second half. “I’m no longer a slave to all of your patriarchal sins.”

A musical restlessness, in the hands of a less capable or confident artist, could result in a difficult, or disjointed album, but Dozier manages to keep I am The Prophet compelling at every turn—the album, truly, still surprises, even months after my introduction to it, in its originality and the way it continues to shift its sound, all while remaining steeped in honesty.

“Intro to Loss,” a short, dramatic, introduction performed entirely on stringed instruments, weaving a motif, sweeping and somber, that is returned to on “No Home”; with its pensive guitar strums juxtaposed against a keyboard twinkling, and Dozier’s moody vocal delivery, is among I am The Prophet’s high-water marks.

As is the dreamy, gauzy “Better Off Alone,” where against shuffling percussion and the unanticipated inclusion of a trumpet, Dozier sways and drifts over a slightly distended, shoegaze-inspired guitar tone, singing lyrics that can be a smirking ode to the “single life,” or an eerie mirror to the disconnection felt during the isolation brought on by the pandemic—“I’ve been spending my time at home by myself,” she explains. “It’s not as sad as it may sound. No romance—no social. I’ve caused enough trouble, I think I’ll stay home. I’m better off alone.”

Perhaps the most surprising still on I am The Prophet is the tenderness found in its dense, lush conclusion, “Left-Handed Lover.” Stirring, ornate, and delicate in its arranging, it also shows a wistfulness and a longing in Dozier’s songwriting that is nearly absent elsewhere on the record. “I miss your hands resting over mine. Hold me while I cry. Sing to me ‘You Can Close Your Eyes,” she pines while the music—complete with wind instruments—flutters and swirls around her.

On Dozier’s more or less abandoned Bandcamp page for Lady Dan, she describes the project’s genre as “melancholic cowboy sounds.” And yes, there are “country” and “western” influences in both Dozier’s personal tastes, as well as a lingering twang, here and there, on I am The Prophet, but as the album’s lyrical content is a reflection of Dozier growth and the creation of her “own moral compass,” the album’s soundscape is a reflection of a different kind of growth—a fearlessness and confidence in songwriting and arranging that remains invigorating with every subsequent listen.

Olivia Rodrigo - Sour

(originally reviewed on June 4th)

In less than two years, I will be 40 years old—a number, an age, whatever, that has been weighing on my mind for quite a while.

And recently, Olivia Rodrigo, objectively one of the biggest breakout pop music stars of 2021, announced her first tour—supporting her debut full-length, Sour. There was a Minneapolis date on her itinerary, and operating with the willing suspension of disbelief that I could set aside my debilitating concert anxiety, and my anxiety about being a crowd during a never ending pandemic, I went through the motions of trying to obtain tickets—registering myself as a “Verified Fan” through Ticketmaster, only to be told that due to the “overwhelming demand” for the tour, even with this fan verification, I was placed on a waiting list, and if I was even able to get tickets after all, I’d be notified of the opportunity.

It might not be surprising to learn I did not receive a notification, and I did not get tickets, which, in the end, was probably for the best, for myriad reasons—one of which is the very high probability I would be the oldest person in the crowd who was not there to chaperone children.

Demographically speaking, Olivia Rodrigo, all of 18 years old, is not making music for a man who is pushing 40, but the more I sat with Sour upon its release in May, the more I came to understand that even though she is more or less writing songs about being a heartbroken, sullen, angsty teenagers, for other heartbroken, sullen, angsty teenagers—if we look hard enough, there are still very heartbroken, very sullen, very angsty teens within all of us somewhere, and in all its bright, Technicolor glory, Sour allows its listener the opportunity to not so much “embrace” those tumultuous, uncomfortable teenage feelings, however far removed we might be from them, but to revisit them, reflecting through the lens of the time that has elapsed.

The emotions, across the board, on Sour are palpable—right from the dizzying opening track, “Brutal,” to the tender closing track, “Hope U R OK,” which, even with its well-meant sentiments, is among the album’s few missteps. And for as brash and enthusiastic (“Good 4 U”), kaleidoscopic and fuzzed out (“Deja Vu”), nervy and slithering (“Jealousy, Jealousy”), dramatic and anguishing (“Driver’s License,” which I will never grow tired of hearing) as it can be in its vitriol, in the end, it is Rodrigo’s surprisingly poignant, somewhat quiet reflections in the aftermath of a messy breakup that are, for me anyway, the most personally impactful and memorable.

“It’s always one step forward, and three steps back,” she sings against a restrained though jaunty piano arrangement. “I’m the love of your life until I make you mad.” Or, in “Traitor,” belted out and perhaps slightly exaggerated for dramatic effect—“I loved you at at your worst, but that didn’t matter.”

Through gritted teeth in the bridge section to “Good 4 U,” Rodrigo utters the phrase, “Maybe I’m too emotional,” and same as I realized in May, after Sour was released, at year’s end, when I hear her say that, I think—yeah, maybe I’m too emotional as well, Olivia. Maybe we all are, and it’s an album like this that provides the reassurance that it is okay if you are.

Emma Ruth Rundle - Engine of Hell

(originally reviewed November 12th)

Engine of Hell is like holding your breath for the entirety of eight songs, and even when the album has concluded, you are never given permission to exhale.

The isolation of the pandemic? The hard feelings and resentment that come from the dissolution of a marriage? The herculean effort it takes to find sobriety and invest in your own mental health? Yes, it’s easy to say that Emma Ruth Rundle’s fourth full-length released under her own name is about all of those things, but it also transcends those quick, easy descriptions to be about something much larger—a haunting, fragile, gorgeous self-portrait of an uncompromising artist.

There are places throughout, even right from the beginning of the record in the song “Return,” where it seems like Rundle is crafting an environment so delicate, everything might unexpectedly shatter. Engine of Hell never does, though, and in pulling inspiration from Tori Amos, Pink Moon, and Sibylle Baier’s Colour Green, Rundle uses skeletal arranging and unflinchingly personal lyricism to confront the darkest, worst parts of herself.

Of course, there is an intimacy that Rundle creates between herself and the listener through Engine of Hell’s lyrics—open, yes, but still partially obscured by a poetic fog that refuses to lift, only revealing what fragments are absolutely necessary. Those fragments are often bleak—the stark commentaries on addictions, specifically, are quite surprising, as are her observations on the ending of her marriage—“Handing down a fistful of sorries you will never say,” from “Blooms of Oblivion,” is among the most memorable lines; or, on “The Company,” controlling the rise and fall of her voice as she sings, “My whole life—some dark night—is so much brighter now without you.”

It is within both of those songs that you hear the other kind of intimacy in Engine of Hell, which is how it was recorded and produced. Rundle, often alone in a room, was left to play or sing out, while producer Sonny Diperri was situation in a different portion of the house the two were using as studio space. There is a slight sensation of claustrophobia within the tension Rundle never really releases throughout, and within that tension, there is also a closeness, which comes through in how Rundle’s voice naturally reverberates off the walls of the room, or in how you can hear every scrape her fingers make across the strings of her acoustic guitar while she’s shifts between chords.

Rundle has implied that she is in better shape now, at the tail end of 2021, than she was when she recorded this album roughly a year prior. Working on her sobriety, she has conceded in interviews for the Engine of Hell press cycle that she’s on better terms now with her ex-husband. The album—the experiences and traumas poured into it, is a means of catharsis, but in that catharsis, there is no resolution. “There is no real hopeful message,” she replied in a conversation with the website Echoes and Dust when asked if there was any hope found within, or just “nothingness.” And that kind of feeling is implied a few places—“There’s no need to check the weather,” she sings in the tumbling, folk-tinged “Razor’s Edge.” “As my winter’s never over.”

Or, as she sings with a snarl in her voice in the album’s final moments, “I have a feeling that I might be here awhile.”

Laura Stevenson - S/T

I hesitate to refer to the opening track on Laura Stevenson’s self-titled album as misdirection, but “State”—volatile and caterwauling, is both Stevenson playing against type, and not exactly indicative of the songs that will follow. Nothing else on Laura Stevenson even comes close to being as explosive as the enormous bursts of electric guitar strums and absolutely pummeling snare drum hits that arrive in the song’s chorus, with Stevenson howling fragments like, “It keeps me alive—it’s easier, right?,” or later on, “My memory fades—and every day, it gets so hot.”

And that’s okay—not everything on the record needs to hit with the same sonic intensity; there’s enough emotional intensity to spare.

Even though it was released during the second year of the pandemic, Laura Stevenson is not a “pandemic album.” The album’s liner notes indicate it was written and recorded near the end of 2019, as Stevenson herself discovered she was pregnant, as well as her dropping everything in order to “help someone that I love very much who was going through something absolutely unthinkable,” as she explained in an interview prior to the album’s release.

And though the material here pre-dates the state of the world over the last two years, there is a nervy sense of anxiety and tension present in this set of songs that is, perhaps, magnified or made to seem exaggerated by what many of us have felt or experienced since March of 2020. She handles those tensions and anxiety with a seemingly effortless grace, and often is able to partially cloak the honesty in her lyricism through the guise of infectious, rollicking, uptempo arrangements.

“Continental Divide” is the song that most lends itself to Stevenson’s worries over becoming a mother—“What could I do right to keep you safe all your life,” she asks, and like so many other questions, or observations she makes across Laura Stevenson, she more often than not, is unable to find the answers.

But it’s on a song like “Sky Blue, Bad News,” where Stevenson’s phrase turns are the most effacing and impactful—“I make amends to everyone that I’ve left standing,” she sings in the chorus; then later, a flicker of self-deprecating hope—“Maybe I’ll be better in a year—maybe I’ll deserve it then.”

“Was I ungrateful?,” she asks at the end of the song, and almost shaking her head in response—“I was, I was, I was, I was.”

Laura Stevenson concludes with what could almost be viewed as an afterword to the album, and it creates such an evocative picture, that in just, like, two minutes, completely stopped me in my tracks during my first listen of the record. In what unfolds like a poem, Stevenson has meticulously chosen her words on “Children’s National Transfer”—“No one knows me in the store—pitiless me,” she begins, describing herself in vivid, sparse language as “another boring customer, frivolously lingering at the soda fridge,” and “Fingering through the rows of chips.”

The song’s surprising, literate, ambiguous final moments, though, are the ones that linger after the album’s finished.

“All my grievance ambulating/I pull in, spinning lights as I watch them go. Lowered eyes and an off-hand joke/Parliaments and a Diet Coke.”