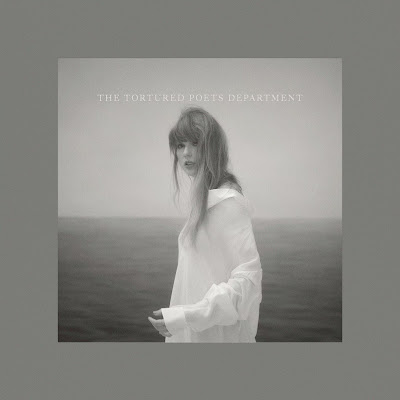

Album Review: Taylor Swift - The Tortured Poets Department

And this is something that I realized—perhaps I had known it all along, or had a suspicion, but something that I really came to understand about Taylor Alison Swift when I watched her perform for over three hours on the Eras Tour.

She is an entertainer.

And, I mean, she is a lot of things. Or, rather, there are myriad words or titles that one could use to describe her. There’s the person and the persona. The songwriter. The artist. The entertainer. The businesswoman, or, perhaps, a better way to describe her, at this point, is as the brand.

Another description, and one that is less endearing for a lot of her fans, is the billionaire.

And it is, I think, kind of impossible or at least ultimately rather challenging to try to compartmentalize these facets of Taylor Swift—the kind of classic artist versus their art situation. Can we, as fans or listeners, still enjoy her music, while reconciling with the things in her life—personally or professionally—that we disagree with, or find troubling?

And maybe if we do not disagree, or do not find it troubling, at least possibly just annoying. Or irritating.

And I mention all of this at the beginning because this might take a while to work through, so here, at the beginning, I will ask for your forgiveness. And all of these things—these elements, or descriptors, are of importance when considering Swift, now, in 2024, and when giving consideration to Swift’s most recent album, The Tortured Poets Department—an album that, while available in seemingly endless configurations of alternate artwork and bonus tracks, is really the convergence, or a collision, of all these things, set to music.

Sometimes, with success.

Other times, less so.

An intimidating and staggering 31 tracks total when all is said and done, The Tortured Poets Department is the sound of Swift wrestling with some of these ideas—the person and the persona, certainly, as well as that of the artist, or songwriter, and the entertainer.

Something that she, more than likely, is not wrestling with, but rather, leaving it up to the fans and listeners to process, is the space that forms in between the artist or the songwriter, and the idea of Taylor Swift as a commodity, or a brand.

Teaming again with her most recent go-to collaborators in both co-writing and producing, Jack Antonoff and The National’s Aaron Dessner, there is a noticeable restlessness that courses throughout Tortured Poets. The songs—yes, all 31 of them, continue to shift, as they please, between the album-specific aesthetics that Swift adopts, which, as my friend Alyssa noted a few days after the release, the album, taken as a whole, speaks to the fact that it was written and recorded while on the road in the spring and summer of 2023, performing a career spanning retrospective two to three nights a week.

That kind of looking back works on stage—the Eras Tour is sequenced non-chronologically, with portions of the show’s running time dedicated to material from nearly every one of her albums up until 2022’s Midnights. With elaborate set pieces, backup dancers, and costume changes, the ever-changing shifts in Swift’s music are noticeable, sure, but the spectacle of the production itself is what makes it more cohesive and less startling.

On record, though, without the dazzling spectacle available to keep us, as fans and listeners, engrossed and entertained, there is a lot less cohesion to be found.

Tortured Poets is a big ask—it runs over two hours, and conceived as a double album of sorts, split into 16 tracks, and then an additional 15. There is a lot to consider within the world of the album itself, and even more to consider within Swift’s world outside of this collection of songs—it does require a lot of patience, and admittedly, the further along you get, especially into the second half, it does begin to test your patience.

It is a big ask, and across the 31 songs, there are a number of genuinely interesting and even surprising moments—songs that are thoughtful and revealing, and songs that are even fun, or clever. But here’s the thing—it’s a big ask. And, I mean, the Eras Tour itself, each night, was a big ask of the audience—to come along for over three hours of music. But, the sets, costume changes, dancers, and the spectacle of it all was what made it so cohesive and engrossing.

In a recorded form, something that does find itself looking more backward than ahead, and lacks the dazzling spectacle to keep the listener entertained and engrossed, is less cohesive, yes, and the main flat with The Tortured Poets Department is that it does begin to buckle under the sheer weight of its own enormous ambitions.

*

And if I am remembering correctly, the last Taylor Swift album that was released through what one could call a “traditional” album roll out, was 2019’s Lover—with singles issued ahead of the album’s arrival in full in August of that year. The following year, both Folklore and Evermore were more or less recorded in secret, and remotely because of the state of the world, and announced, like, the day before they were set to be released.

Midnights, arriving in October of 2022, was originally announced around two months prior, and in lieu of advance singles of what her fans and listeners could anticipate from the album’s sound, the rollout included the slow reveal of song titles and other clues surrounding the project through a series of videos on Instagram, with the tone, and aesthetic of the album up for speculation until everyone crowded around their computers when October 20th became October 21st.

She asked us to meet her at midnight. We obliged.

The Tortured Poets Department’s strategy was similar—announced during the Grammy Awards as Swift collected the trophy for “Best Pop Vocal Album,” for Midnights. But rather than slowly teasing the song titles in the weeks leading up to the release date, they were announced the day after she shared the news that a new album was imminent.

Originally billed as a 16-track album with a bonus track listed, “The Manuscript,” like Midnights before it, where it was implied, and encouraged, that listeners bought upwards of four physical copies of the album—the vinyl editions available in different color pressings—with four different front and back cover variants—Tortured Poets, regardless of how you may or may not feel about the songs themselves, is a project that arguably blurs any lines between Swift as a singer, songwriter, or artist, and Swift as a businesswoman, and a “brand,” because it is, again, encouraged and implied that listeners, if they wish to, or have the disposable income to do so, purchase multiple copies—of the four editions made available, each features a different cover photo, and each has its own bonus track tacked on at the end of the album’s run—“The Albatross,” “The Bolter,” and “The Black Dog,” all of which were then included in the surprise, expanded version of the album, revealed only hours later.

Taylor Swift, as an artist, and songwriter, and a businesswoman, can do whatever she wishes to in terms of her album release—as many variants as she wishes, and as many variant specific bonus tracks as she wants to include. In just specifically looking at the production of the vinyl editions of Tortured Poets, I mean, yes, she apparently, per the data in Wikipedia, sold 700,00 copies of the album on that format alone within the first few days of its availability.

But as an artist of her magnitude, she has already faced some criticisms about what pressing an enormous album like this does to what was once and still is technically a very niche market, with limited resources worldwide—with the criticisms being that in trying to meet the demand, this makes it difficult, if not impossible, for smaller, or very indecent artists, to send their record off to be pressed onto vinyl in a timely fashion.

Taylor Swift, as an artist, and a songwriter, and a businesswoman, or a brand, or a commodity, can do whatever she wishes in terms of her album release. She can make as many variants as she wishes because she knows, at the end of the day, that she has a captive audience. That there are fans, or listeners, who will buy all four iterations—on CD or on vinyl—and while she should feel empowered to market the album the way she wishes, for me, and perhaps for you as well, it creates a barrier of sorts. It doesn’t mean I enjoy the album less or that I would enjoy it more if there weren’t so many different editions with different additional tracks included.

It creates a barrier because I see it as a cash grab, to take more from an audience that has presumably given so much already—financially and otherwise. It feels weird. And that weirdness then does create, for me, and perhaps for you too, a shadow that does loom over the album as a whole.

*

I love you. It’s ruining my life.

And because I am not on a deadline, for this, other than my own, with even as intimidating as it is to sit down with The Tortured Poets Department as a listener, let alone as someone who wishes to write about it analytically—and doing so with thought, and care—I took my time listening, and just simply listening, until I could make the time, and the space, to sit down, both literally and figuratively, to begin compiling my notes on all 31 songs.

The notes that I take are, I suppose, a safe space for me to loosely write down my experience with the songs, often based around the feeling I am getting from the instrumentation or the way the song is unfolding.

And, of course, the lyrics.

And I mention these notes that I meticulously take—stopping and starting a song in order to best articulate my thoughts before moving on to the next one, because while it is a space where the thought and care begin, which I do inevitably hope carries over and is apparent within the piece in question, it is also a place where I can make a joke, or ask questions—often rhetorical—all of which I might not even come back to.

“Is this an album about Florida?,” and, “How long of a measurement of time is a fortnight, actually?,” are two questions that I did write down within my time spent with the hushed, ethereal, shimmering 80s pop-influenced opening track to Tortured Poets, “Fortnight,” which features one of the album’s two guest appearances—this one includes subdued, and honestly pleasant additional vocals from Austin Post, professionally known as Post Malone; the other featured artist is Florence Welch—the namesake of the group Florence + The Machine, who appears midway through the first part to the album, on the campy and bombastic story song “Florida!!!”—stylized just like that with the exclamation points.

How long is a fortnight—it is two weeks.

Is this an album about Florida? No.

Not really.

But it is perplexing to me that the state itself appears in two songs—Malone quietly sings in the closing portion of “Fortnight,” “Move to Florida—buy the car you want, but it won’t start up ’til you touch, touch, touch me,” with the Sunshine State being both a location and character of sorts in “Florida!!!,” with the line, “Fuck me up, Florida,” delivered by Swift and Welch with a mix of earnestness and a self-aware wink to the listener.

“Fortnight,” as an opening track, is not indicative of the album’s aesthetic, considering just how restless Swift is across the album’s sprawling 31 tracks, though the nostalgic, glossy sound it boasts, with production and co-writing credits attributed to Jack Anontoff, does in a sense continue the synth-heavy pop sheen of the two’s work on Midnights.

Swift, as a songwriter, even early on, is known for writing herself into her songs—and she does that a lot, certainly, across Tortured Poets, but there are also places where she blurs the line between her truth, or her experiences, and a crafted narrative. “Fortnight” is one of those places—she’s vivid with her imagery right from the gate, and it is bleak, which serves as a contrast to the more relaxed feeling the song has overall. “I was supposed to be sent away, but they forgot to come and get me,” she begins. “I was a functioning alcoholic ’til nobody noticed my new aesthetic.”

The lyrics, then, become darker the further she takes us into the song—creating a portrait of former lovers attempting to be cordial, or as it is implied, neighborly with one another, even though it is cause for unrest within Swift as the protagonist. “For a fortnight, there we were forever,” she muses in the slinky chorus. “Run into you sometimes—ask about the weather. Now you’re in my backyard, turned into good neighbors. Your wife waters flowers—I wanna kill her.”

This temperament continues when the chorus returns, though the object of her discontent has been changed. “My husband is cheating. I wanna kill him.”

There is a smolder that courses, albeit very slowly, and subtly, in “Fortnight,” and I think what I find to be genuinely interesting about it as a song is a single line, repeated a handful of times, within both the second verse and the bridge that does get us to the song’s dazzling conclusion, and also the production of the song itself—there are myriad places throughout Tortured Poets where Swift’s voice is run through effects, or is manipulated in some way, but here, there is this strange, yet compelling distance that is created—a little cavernous, a little somber, a little haunting. It sounds like she’s singing the song miles away from where the synthesizers and steady rhythm of the drum machine are coming from; and the instrumentation itself is structured around this idea of not so much tension, but there is a restraint. It’s a song that does eventually take off or go somewhere—the ending, where Malone takes over most of the vocals, but even then, it never really takes off or ascends, but rather, stays in a low-to-the-ground holding pattern.

This kind of weird distance, or quiet, that I noticed in “Fortnight” can be heard elsewhere on the album, specifically within the first four or five songs. And because it’s Taylor Swift, I feel like that kind of long, slow burn, or more restrained approach to the songs, has to be intentional.

As one maybe could have anticipated from both the title of the album itself, but also from Swift’s penchant within her songwriting, there is an awful lot of longing throughout the album’s 31 songs—sometimes executed more successfully or more palpably than others. “Fortnight,” even in within the kind of shimmering whisper it is, is one of the songs where the longing is subtle, but effective, with Swift saying putting so much heft into a single line.

“I love you. It’s ruining my life.”

And I think it works because it is stated so plainly. She isn’t pleading with the antagonist within the song. It is simply what she is experiencing. And that’s the thing. She’s still experiencing it and why it is impactful is because it isn’t the past tense. It isn’t “loved.” The love is still present, somehow, even if it is in fact ruining her life.

*

And so, like, here’s the thing—the thing that I am realizing or coming to have a better understanding of the more I try to organize my thoughts about The Tortured Poets Department. It is that with an album of this size, or scale, both literally in how it was released, and what its sales expectations are, but also metaphorically because it is a sprawling double album that does truthfully become quite sluggish in its second half, it becomes hard to only talk about the music itself, or your experience with the music, because there are ultimately, so many other things swirling around, informing how you feel.

I am not sure if the early criticisms of the album were able to articulate this with any kind of clarity—the pieces that were, unlike this one, on a deadline with an editor breathing down the neck of a harried music writer, but after the first week, and in giving the album more than one listen through, the fatal flaw that it does reveal is how sonically, in Swift looking backward more then ahead, across so many songs, the impression it leaves—outside of the idea of the album release being an event, or whatever, from a marquee name pop star—is that a lot of these songs feel rather familiar.

Not that they’ve been “done before,” or in the past done better, or executed with more success—well, I mean, yes, maybe in a few examples. But. There is this notion of similarity in a number of places—similar melodies, vocal deliveries, arranging, etc.—and maybe, for some listeners, there are some small comforts in Swift returning to what worked for her before. But in returning to what worked before, with just minor alterations, it does run the risk of creating an album of diminishing returns.

It is an album that challenges the listener in the wrong way. Or rather, in a way that I wish it didn’t. It lacks the challenge of an artist pushing themselves into something new, or genuinely interesting, with the challenge coming in the form of just finding the patience and the grace to sit with the album, beginning to end.

Swift, with Antonoff in tow, continues to revisit the vintage, synth-heavy sounds of both 1989, and their work together on Midnights, in other places within the album’s first half—like within the bouncy, dreamy, self-aware title track. And, like “Fortnight” before it, there is this actual distance between the music itself, and the listener. Swift’s vocals are pushed up to the front a little more here, but the snare hit coming from an antiquated drum machine, and the twinkling keyboards all sound like they are miles away. There’s an airy feeling—but in its airiness, it is not giving you room to breathe.

And so, like, here’s the thing—the thing that I am realizing or coming to have a better understanding of the more I try to organize my thoughts about The Tortured Poets Department. Is that it is almost impossible not to let the debate about person and persona, and artist and the art they make, begin to influence how you feel or what your experience is with specific moments on the record.

Prior to its release, I was not certain what kind of album Tortured Poets would be—like, what it would be about, and what it would sound like. Was it going to be an album reflecting on the breakup of Swift and her longtime partner, Joe Alwyn, who apparently split up in early 2023, just as she was embarking on the Eras Tour. Was it going to be an album about the beginning of her new relationship, in the autumn of that same year, with Kansas City Chiefs tight end Travis Kelce?

Or, would it be about the Matt Healy of it all?

For as short as their courtship was, in the spring and early summer of last year, a lot of the songs on Tortured Poets, including the title track, are allegedly allegedly allegedly about Healy—the polarizing frontman from the group The 1975.

Lyrically, it is the first place on the album—the first of many, where Swift is unabashedly self-referential and self-aware, which is something that she has, of course, done in the past, and at times, does well, or with tact. And, I mean, there are places on Tortured Poets where she is able to write herself into a song with success, but there are a number of places here where it is cringe—and if not cringe, extremely uncomfortable in how it addresses its subject.

Healy, himself, is implied to be the tortured poet, though it is implied in the chorus that Swift herself could be one as well, with the expression being a veiled reference to the film Dead Poets Society, then proceeding to name-drop Dylan Thomas, Patti Smith, and the famed Chelsea Hotel, though in the self-aware world of the song, she is incredibly deprecating towards herself, and her antagonist. “You’re not Dylan Thomas,” she chides. “I’m not Patti Smith. This ain’t the Chelsea Hotel—we’re modern idiots.”

The way Swift depicts this whirlwind romance, at least here, is more than a little cloying, and extremely revealing, but what it is most impactful about that, even in the grimace and the eye roll that some of these lyrics cause for me, is the kind of unhinged desperation and urgent longing that was potentially at the core of their entanglement. Sure, you can hear it in the way her voice rises into that breathier, higher register when she asks the questions, “Who’s gonna hold you like me?,” and “Who’s gonna know you if not me?,” to which she answers by saying, “Nobody,” then emphasizing it by adding, “No-fucking-body.”

And, if I may, and if you will indulge me in a slight aside, before I continue talking about the titular track to the album, I do wish to discuss how, over the last four years, since the release of Folklore, which to my knowledge, was the first Taylor Swift album to be stamped with the Parental Advisory sticker on its cover, when Swift does opt to include profanity in her lyrics, I am hesitant to say that it is disingenuous, but there is a part of me that still feels like it sounds as if she is saying a “bad word” for the very first time in her life and cannot stop grinning at what an act of rebellion, or whatever, it must feel like for her.

The “No-fucking-body,” here, feels like a little much; like it doesn’t add anything to the song to punctuate it that way.

“Tortured Poets”’s bridge arrives as less of a bridge, with so much packed into it, it is truly aa third verse before the final chorus; and it is the verse with the lyrics that did make me recoil—out of embarrassment and surprise, the first time I heard them.

“Sometimes I wonder if you’re gonna screw this up with me,” Swift asks. “But you told Lucy you’d kill yourself I ever leave. And I had said that to Jack about you, so I felt seen.”

The Lucy, here, is Lucy Dacus; the Jack is, of course, Jack Antonoff. And maybe it is the way that these people, and their names, are so casually mentioned within the context of something seemingly serious, though dealt with in such an off-handed way. And maybe it is the off-handed and borderline intensive way that Swift sings about the idea of suicidal ideation1.

Or maybe it is because in the heightened sense of drama, desperation, and urgency that is fueling this relationship, there is a sadness that hangs over it, even without well-meant, I think, a lot of these sentiments are, because you know how quickly it self-destructed.

This kind of cringey, wincing, self-aware songwriting, as well as the feeling of the familiar in terms of arranging and production, returns later on within the first half of Tortured Poets, on the kind of funny, kind of cloying, “I Can Do It With A Broken Heart.”

With instrumentation—twinkling, jittery, whimsical synth arrays that I assessed, in my notes, as sounding “Bejeweled”-adjacent, Swift sings, with a little bit of a playful smirk, and wink, to the listener, “I’m so depressed I act like it’s my birthday every day,” in chorus to “Broken Heart.” “I cry a lot but I am so productive—it’s an art,” she adds, just a few lines later. “You know you’re good when you can even do it with a broken heart.”

The lyrics are a lot—there is no question about that; and they are contrasted with such a saccharine, up-tempo, glittering arrangement of keyboard beeps and boops, almost not moving fast enough though to keep up with her delivery (there is like just the smallest bit of dissonance, or like weird feeling of unease in this song, at least for me)—and that contrast is a lot as well. It was surprising during my initial listens, and it still can be just a little jarring now, even though you are anticipating it. So regardless, I guess, of how cringe or wincing the whole thing might make you feel, “Broke Heart” is memorable for its quotable chorus, as well as the pulsating, witting beat that ripples underneath the mostly spoken part of the song, leading up to where the chorus blinds its listeners.

Perhaps just slightly less to deal with, or unpack, Swift finds a groove to fold herself into as she rhythmically utters, “I’m a real tough kid—I can handle my shit. They said, ‘Babe, you gotta fake it ’til you make it’ and I did,” some of which echoes some of the more personal revelations about the earliest days of her career, or at least what it is like balancing a personal life with a persona, found in the Midnights track, “You’re On Your Own, Kid.”

“Lights, Camera, Bitch—Smile,” she continues through gritted teeth, leading to the surprising admission. “Even when you wanna die,” which does imply, as does a line that comes a little later, “Breaking down, I hit the floor. All the pieces shattered as the crowd was chanting ‘more!’,” that parts of this song, at least are a reflection on the dissolution of her longtime relationship with Joe Alwyn, the news of which broke shortly after the Eras Tour had started.

*

There is no question that Taylor Swift, as she has grown, has proven herself again and again, with each album, to be an extremely talented and often thoughtful or clever songwriter—and a very dynamic one at that. She can write something heartbreaking, or poignant in the emotions it conveys; and she can write a pop song that is just undeniably fun as hell to sing along to.

The thing with Tortured Poets is that the songs here are not, like, “bad,” or anything, and I am not implying that she has lost her ability to turn a phrase or craft a soaring melody. Not at all. But I think within the album’s absolutely sprawling runtime, the problem it faces is how are these songs, which were all apparently important enough to Swift, or considered to be good enough, to be included within what was ultimately conceived as a double album, able to stand out from one another. How do songs not get lost not even within the shuffle, but just lost within the sheer volume of material found here.

Specifically, within the latter portion of the album’s second half, and I never thought I would find myself considering this to be a fault, or a problem within Taylor Swift’s output, but within my notes on Tortured Poets, I considered that there were ultimately too many slower songs featuring the piano, which brings any kind of momentum or liveliness that the album might have had down to a glacial pace.

Because with there being what seems to be just, like, too many songs of this nature, how do really make the space for one, and find what truly does differential it from the others, or what makes it potentially more genuinely interesting to listen to.

And even if the kind of fatal flaw, aside from its cumbersome running time and the enormity of the ask to sit with something this intimidating, is the similarities, or familiarities to previous compositions, there are quite a few places, both within the album’s first and second halves, where there are moments that allows for a song to set itself apart from the rest.

And, yes, I would say that the metaphor of “jail” is perhaps a little overextended in the slinking, sparse, “Fresh Out The Slammer,” or maybe it is just a little bit of a perplexing conceit to use within the song itself; and yes, the way she sings the titular phrase—“Fresh. Out. The Slammer. Ahhh,” before the song’s chorus is something Swift has most certainly used the past, as are the swaying, up ticking inflections she puts on the syllables within the chorus itself.

But.

Even with these seemingly familiar elements that are woven into the song, there are things about it that I did find unique or at least surprising.

“Slammer” is one of the 16 tracks attributed to co-production by Jack Antonoff, though here he does away from the synth-heavy twinkling and glistening that the earlier tracks on Tortured Poets he worked on have, and instead, he works on a kind of gentle, slow convergence of more organic textures with a more slinking and reserved feeling coming from the pinging of the percussion that comes in underneath.

The interesting textures, at least for me, come in the form of the quivering, twangy electric guitar that you hear at the beginning, and throughout, as well as the dissonant, or at least darker sounding strummed guitar rhythm that is tucked subtly within the mix. And what does make “Slammer” one of the more interesting or noteworthy songs is the sudden shift it makes in tone shortly before it arrives at its conclusion.

The song itself is, like, three-and-a-half minutes in length, moving at a slower, smoldering kind of tempo, but with roughly a minute left, there is this abrupt change that occurs, with a new, skittering, programmed percussive rhythm coursing through, while Swift breaks off what she was singing, mid-lyric, and begins this kind of mostly rapped, kind of sung epilogue, that unfurls seemingly stream of conscious and almost breathlessly delivered as she races toward one big dramatic exhalation at the finish line.

“Now, pretty baby, I’m running,” Swift in a huskier register, and without breaking her stride, begins stretching out the syllables and breaths, allowing certain words to be extended or to be punctuated within the hit of the rhythm. “To the house where you still wait up, and that porch light gleams,” she continues. “To the one who said I’m the girl of his American dreams. And no matter what I’ve done, it wouldn’t matter anyway. Ain’t no way I’m gonna screw up now that I know what’s at stake here, at the park, where we used to sit on children’s swings,” Swift says, urgently, but patiently, and effortlessly creates an extremely vivid image within this short narrative. “Wearing imaginary rings.”

“Fresh Out The Slammer” gets very quiet after this, and you would think that the song, then, is over, suddenly—perhaps just as suddenly as it moved into this other direction. But, after a pause, Swift sings, “But it’s gonna be alright. I did my time.”

And there are these moments, of course, and maybe they can get lost in all the pop bombast, or the theatricality, or moody and somber, or anything else that informs how we, as listeners, and fans, might be feeling about The Tortured Poets Department, but even within a song like “Fresh Out The Slammer”—there are these small details you can begin to ruminate on. Not about who this song is about, exactly, but like the fact that it provides no easy answers, as Swift, or at least Swift as the protagonist, is both running away from something and toward something else, with an unease, and uncertainty, about each.

*

And this is not something that I really had considered, or, really, even a lot of experience with myself, but as the summer became the autumn in 2022, and both Taylor Swift and Carly Rae Jepsen were releasing new albums on the same day—the tracklist to Jepsen’s The Loneliest Time revealed around the time the album itself was announced, and Swift revealing, slowly, the names of the tracks on Midnights.

I tell you all of that to tell you this. But maybe this is something that has happened to you, where you see what a song’s title is, and until you hear it, you speculate on what it might sound like, or what it might be about—only to, perhaps, be a little disappointed, in some regard, once you are able to listen.

And maybe this was something that had happened to me, in the past, that I had not even really given much consideration to, but as the summer became the autumn in 2022, my friend Alyssa expressed how much she did not like knowing the names of songs this far in advance before she was able to hear them—because then you do speculate, or wonder, or have a vision in your heard (or rather, your ears, I guess) of what you think it will sound like, based on the title.

Then when you get to hear that song, upon the release of the album, if you speculated, or wondered, in the months or days leading up to that moment, you may ultimately feel disappointed. Or annoyed.

I tell you all of that to tell you this. That, even if I was not, in the past, putting as much stock in what something might sound like, or be about, based on the revelation of its title, in advance, I did have, in my mind, an idea of what I had hoped the song “The Black Dog” would be about.

It wasn’t about that.

And it isn’t exactly an obsolete expression, or description—but it is one that I do not believe is commonly used at this point.

He is not credited as the first one to describe depression as a “black dog,” but Winston Churchill did popularize the expression for a time. So it is, then, also, a very English way to detail one’s depressive state. Before his alleged death by suicide in 1974, one of the final songs Nick Drake wrote and recorded was the haunting, brooding “Black Eyed Dog.”

A stark, though accurate, meditation on the depression that Drake had been suffering from, the lyrics are sparse, and sung through gritted teeth, but are incredibly effective in their portrayal of the shadow that does, literally, always loom. “Black eyed dog, he called at my door,” Drake sings in the song, his voice terribly fragile. “The black eyed dog, he called for more. A black eyed dog, he knew my name.”

Then, in the short song’s second verse, maybe even more harrowingly—“I’m growing old, and I wanna go home.”

And I was, of course, aware of “Black Eyed Dog” for almost two decades before I really listened to it, and put together what it was about—and it was, honestly, the slow-moving and sentimental single from Arlo Parks (again, also English), “Black Dog,” that assisted me in making the connection.

“I’d take a jump off the fire escape to make the black dog go away,” Parks sings, sweetly, and tenderly, to a friend who is in the midst of a depressive state—which is depicted with a kind of graphic, poetic honesty, throughout the rest of the song.

And for as many as Swift’s songs, in the past, are about melancholy, “The Black Dog” is not one of them.

“The Black Dog,” which is one of the four bonus tracks selected to be tacked on at the end of one of the four physical editions of The Tortured Poets Department, is not about mental health. Well. I mean. Not really. It’s a breakup song—or, rather, about what happens after a relationship has come to a tumultuous end, what feelings remain, and what Swift, as protagonist, is supposed to do with those feelings.

In Swift’s song, “The Black Dog,” is much less of a metaphor, and is the name of a place—a bar, where her former partner has seemingly found himself, perhaps with a new, and younger, lover on his arm, and potentially, a little bit of longing in his heart.

Lyrically, “The Black Dog” hinges on a moment, or at least a want, within a moment. Okay. Well. Maybe two moments—one, lyrically, yes, with the kind of narrative that Swift creates with literally just using two or three lines, but also one of the very genuinely surprising moments, musically, and structurally, that occurs within the chorus.

The backstory behind the heartbreak, and the conflicted feelings, and the inevitable bitterness, and palpable longing, all kind of unfold within the verses—the bitterness, specifically, rises to the top within the bridge.

But it is this moment, as she heads into the chorus, where it isn’t posed exactly as a question, but there is an ask. “I just don’t understand how you don’t miss me in The Black Dog,” she exclaims, and, yes, the way the words, and syllables of those words are specifically emphasized, is extremely familiar and is a device, within a song, that Swift has done countless times before. From here, she does make a surprising reference to the 2000s-era pop-punk/emo adjacent band The Starting Line. “You jump up, but she’s too young to know this song that was intertwined in the magic fabric of our dreaming,” Swift muses, with some resentment, and sorrow, building in her voice.

And it is that building. You see. That is the moment. Because while what leads up to it is certainly a melody that Swift has deployed before in her music, and will, most certainly, use again, it’s the way that she carries the line, “The magic fabric of our dreaming,” and allows it to soar, and then, as she bellows, “Old habits die screaming,” the music, at least temporarily, explodes in cacophony around her. It’s startling. In a good way. Like, expected, in a sense, because you can tell that she is leading you towards something larger, and expected because of the use of the word “screaming.” But it, and the small portion of the larger narrative that occurs right before it, create such a powerful, and lasting moment.

*

Something that did give me reason for pause, initially, when Swift announced The Tortured Poets Department, and something that I know I am not the only person who has considered, is that it seemed like, perhaps, there had not been enough time since the completion and then eventual release of Midnights, until now—I mean, Swift objectively hit a prolific streak in 2020 with the back to back surprise releases of Folklore and Evermore, but both of those were admittedly brought on by the isolation of the pandemic.

She is also—and, I mean, really, I have no idea when she has carved out the time, or how much time it even takes, but Swift is still working her way through her back catalog, and re-recording and reissuing her first six albums, as part of the world’s longest “fuck you” to the head of the label she was initially signed to, Big Machine.

In 2021 and 2023, she did reissue four of those six albums, complete with supplemental “vault” material. And, I mean, she also spent nearly all of 2023 on the road with the Eras Tour. And, yes, there were days off in between performances—she really only performed on weekends, but with the rigor of the schedule, has enough time passed between the end of 2022 and now? Sure. Let’s say that a little over a year is time enough to begin a new album cycle.

But has enough time passed, and has Swift had enough time to really focus on writing and recording?

There are moments on Tortured Poets that say yes. Or, if anything, the rollout to the album says that she has had time to plan the business end that comes along with a new release. But there are moments on the album that say no. That she did not have the time to totally dedicate, and the longer you sit with the album—and the longer it gets, and yeah okay she had enough time to write and record 31 songs but, there does become a threshold of diminishing returns.

Is it an album that does suffer because it was, potentially, too rushed to be as thoughtful as it could have been.

You can see, or I guess hear, rather, the faults in Tortured Poets throughout, but there are places where the lyricism is so rough it moves beyond the aforementioned cringe into something else entirely.

Like the word embarrassing doesn’t seem to do justice to how uncomfortable and perplexed I was by the writing, or at least some of her choices on the songs “So High School” and “I Hate it Here,” both of which are tucked away in the second half of the album’s sequencing.

Even though a lot of the lyrics elicit an eye roll, or a groan, specifically in the bridge, what Swift does well on “So High School” is that she very meticulously captures a feeling—a kind of nostalgia that premeditated in such a way to emulate the sound a teen comedy from the latte 1990s—a similarly cinematic technique that you can hear on the song “Drew Barrymore” from SZA. And yes, some of the less cringey lyrics, or at least the lyrics that are slightly more palatable, assist in this—“I’m watching America Pie with you on a Saturday night. Your friends are around, so be quiet—I’m trying to stifle my sighs,” Swift coos a little after the chorus, which does create a vivid image, regardless of how the lyric itself makes you feel.

This feeling, though, does really happen, thanks to the song’s instrumentation and arranging. “So High School” is one of the 17 songs that Aaron Dessner is credited as a co-writer and producer on—and here, he does manage to play against the kind of production and aesthetic corner he has kind of backed himself into when it comes to his collaborative work with Swift over the last four years. There is a very real 1990s “alternative rock” edge to the song, with the slightly dissonant, slightly jagged sound of the electric guitar strums that it opens with, and then later, as it picks up momentum, the sharp crunch in the way the drums sound.

And so, yes, musically the song is unique for both Swift and Dessner in terms of being something quite different in comparison to the sounds they have favored or gravitated towards in the past—this does help it really lean into the kind of nostalgic, wistful feeling they are conjuring. But. The second hand embarrassment that does come from some of the writing on “So High School” makes it a hard one to sit with.

“Truth. Dare. Spin bottles,” Swift sings during the bridge. “You know how to ball—I know Aristotle.” Which, I mean. I get it. The rhyme scheme works and it is cutesy but not like unforgivable. “Brand-new, full throttle,” she continues. “Touch me while your bros play Grand Theft Auto.”

And there are, unfortunately, equally as uncomfortable, if not more uncomfortable, or if not more questionable, lyrics in the song that follows—the acoustic-tinged and swooning “I Hate It Here.”

“I Hate It Here” is another collaboration between Dessner and Swift—and it, like, I would say a bulk of the material on Tortured Poets that the two worked on together results in things that sound similar, or akin, to their previous collaborations across Folklore and Evermore. And I mean, maybe that is not a bad thing. It’s not necessarily a bad thing. There is a critical part of me that feels like the novelty has worn slightly, or the spark that the two originally had when they first began working together is starting to dull slightly.

Or, if not wearing or dulling, maybe there are just entirely too many of their songs together centralized in the album’s sequencing, without enough dynamism to provide balance.

“I Hate It Here” moves along quickly, and is rather delicate and quite beautiful in a number of ways in terms of how Swift’s voice sounds, and how Dessner dexterously plucks away at the acoustic guitar strings, giving way to his penchant for cavernous, often mournful piano chords. It works. And it works well. And even though the song opens with a little bit of a smirking, cloying lyric from Swift—“Quick quick. Tell me something awful. Like you are a poet trapped inside the body of a finance guy.” Even with a phrase turn like that, she does recover, though, in the very next line. “Tell me all your secrets,” she pleads. “All you’ll ever be is my eternal consolation prize.”

Something that Swift has explored previously, and does continue to explore in a few places on Tortured Poets is not where she is from, per se, or like going into great detail about her upbringing, but rather, she provides these small but very telling details that give the faintest impression of reflection on her past. Or, as much as she is interested in reflecting, and as much as she is interested in revealing. Here, within the restrained but swooning, shimmery chorus, Swift refers to herself as a “precocious child,” and there is almost not a sense of arrested development in Swift exactly, but she does, as the song continues, further develop the idea of her precocious nature both as a child, and as a woman in her mid-30s.

And there has been, and rightfully so, a lot of criticism, and if not criticism, just a lot of head scratching and jokes at the expense of the conceit of the song’s second verse—one line, in particular, that is just terribly out of touch.

“My friends used to play a game where we would pick a decade we wished we could live in instead of this,” she begins. “I’d say the 1830s, but without all the racists and getting married off for the highest bid.”

The knee-jerk responses to a line like that are warranted, because there is an awful lot to unpack, and it, for me, and potentially for you, did not land. At all. And it is so surprising in its seeming tone deafness, and privilege, that it does pull you right out of the world of the song, where you can’t really focus on anything else that might be occurring—bad, or good.

But in pulling us out of the world with a line that was, more than likely, designed to shock, or startle, and I am kind of surprised that with the “team” that certainly is working with Swift on a day-to-day basis, nobody stepped in to ask if she was certain she wanted to use those lyrics—but in pulling us out of the song, what is ultimately missed is Swift’s attempted explanation as to why she wished to live in the 1830s, BUT without the racists. Because what comes next is the reveal that romanticizing the past ultimately overlooks the troubling things of the past you wish to feel nostalgic or romantic about.

“Everyone would look down ‘cause it wasn’t fun now,” she continues. “Seems like it was never even fun back then. Nostalgia is a mind’s trick—if I’d been there, I’d hate it. It was freezing in the palace.”

It’s a weird thing—those next few lines. It doesn’t double down, and it doesn’t apologize. It attempts to make an excuse, or explain the reasoning, but those lines, like the main point the verse is trying to make, falls terribly short of whatever good intention Swift had when she began working on the song.

*

How much sad did you think I had—did you think I had in me?

And here’s the thing about The Tortured Poets Department—it, in the end, is an album that does run the risk of collapsing under the magnitude of its own enormous ambitions, or, if anything else, the risk of being overshadowed by its mythology and lore.

And within all of that, there are relatively straightforward songs that do work, and over time—yes, you might even need more than two or three weeks to truly feel a real connection to some of these songs—you may even warm up to some of the ones that did not originally resonate.

And, there are ones that might not ever resonate. Or, for whatever reason—lyrics, or otherwise, might keep you at arm’s length.

And, still, there are moments on this album that are quite spectacular—and I do thank you, of course, for your patience, because we will eventually be arriving there.

And, still, maybe more than those moments that are spectacular, or do blind in a flash of brilliance or exhilaration, there are moments where Swift and her collaborators find themselves in territory that is, in a sense, unfamiliar to them—something uncharacteristic and genuinely interesting to hear within the context of the record as a whole.

The speculation, once the original tracklist for Tortured Poets was announced in February, was that the song “So Long, London,” would more than likely be about the end of her relationship with actor Joe Alwyn, whom she was involved with for roughly six or seven years—and whom is credited as a co-writer, under a pseudonym, on a few of the songs from Swift’s Folklore and Evermore era material.

“So Long, London” is, of course, a breakup song—or, at least, a song that takes a long, cold look at the slow, final days of a relationship that had, at least as it is depicted here, exhausted its course and was, allegedly limping along.

Swift does, in the writing, while low, glitchy synthesizer patterns ripple and shiver underneath her quickly, point the finger, but she does so subtly. She isn’t angry, exactly, but sounds embittered and frustrated with both the way things dissolved, and what she has come to understand in the time that has elapsed.

“I kept calm and carried the weight of the rift,” she declares in the song’s opening verse. “Pulled him in tighter each time he was drifting away. My spine split from carrying us up the hill—wet through my clothes, weary bones caught the chill. I stopped trying to make him laugh,” she continues. “Stopped trying to drill the safe.”

Her musings become even darker in the second verse, and the imagery used within the second appearance of the chorus. “I stopped CPR—after all, it’s no use,” Swift confesses. “The spirit was gone, we would never come to,” she adds, before the most damming line that does, even in the ambiguity of who this song may be about, reveal just enough for a confirmation. “I’m pissed off you let me give you all that youth for free.”

“Two graves—one gun,” she says somberly, just a few lines later.

It has been joked that Swift could be an expert at infrastructure with the kind of bridges she is capable of writing into her songs—and the truth is that a number of the bridges on Tortured Poets are just not as impactful or anthemic as others she has penned in the past. But on “So Long, London,” she does really go for it, and it does really work—the music itself more or less remains in a place of tension with little, if any, release, with her voice being the thing that rises up. “And you say I abandoned the ship, but I was going down with it,” she reflects. “My white-knuckle dying grip holding tight to your quiet resentment.”

And there is a question that Swift returns to in “So Long, London”—one that she asks and never receives an answer for, and one of the more inherently dramatic lyrics that does make a dramatic, and emotional fan and listener, like myself, feel seen.

“How much sad did you think I had,” she says quietly in the chorus. “Did you think I had in me.”

In the album’s sequencing, “So Long, London” is placed fifth, and it is the first song within the album’s sprawl that is produced and co-written with Aaron Dessner—and while he, as a producer and arranger, has not shied away from the use of drum machine rhythms and synthesizer tones in his work with The National, Swift, or others, here there is a melancholic hush and shadow that he has not exactly explored before in such a direct way. It is refreshing, and the reserve shown in both Swift’s vocal performance and the music that courses below her, gives the song this sense of unease that, in the end, finds no resolve.

Placed near the top half of the album’s second part, and musically, it does find Dessner’s production and instrumentation returning to the aesthetic that he knows and often favors—quickly, but delicately plucked acoustic guitars, mournful, cavernous piano, and little, intricate electric guitar flourishes to punctuate within the chorus, but the stark “Chloe or Sam or Sophia or Marcus,” is another point of genuine interest in how Swift, poetically but also with a surprising frankness, unpacks the apparently messy end to a relationship.

The gentle and hypnotic instrumentation gives the song an unadorned quality that does allow you to focus on Swift’s lyrics, and the kind of pensive way she sings them. And there is of course the desire, small or large, to try and figure out who Swift’s songs are about. Sometimes, she hits you over the head with it—something she does a few times on Tortured Poets, like the eye-rolling football references she rattles off in “The Alchemy.” Sometimes the songs are vague, but with a little wink, or a smirk, as a means of direction to the listener.

But sometimes they are very ambiguous. And, I mean, sometimes the songs aren’t really about her. Or her directly. They are story songs, or songs where she is playing a character or an exaggerated version of herself.

So there is a sense of curiosity about “Chloe or Sam,” and Swift chooses her words well right from the opening line as a means of pulling us into the narrative she’s crafting. “Your hologram stumbled into my apartment,” she begins quickly and contemplatively. “Hands in the hair of somebody in darkness named Chloe or Sam or Sophia or Marcus,” she continues. “And I just watched it happen.”

And there is speculation that the song is another one about her short-lived and seemingly tumultuous relationship with Matt Healy—“You saw my bones out with somebody new who seemed like he would have bullied you in school,” is a more than telling line about the contrast between the pompous and arty frontman of The 1975 and Swift’s current partner. But there is a much more harrowing line that comes in the second verse: “You said some things that I can’t unabsorb. You turned me into an idea of sorts. You needed me, but you needed drugs more—and I couldn’t watch it happen.”

And, even with the biting, or at least remorseful lines like that, implying a kind of darkness that clouded Swift’s time with Healy (allegedly), there is a real hurt that rises to the surface here—a hurt that is still fresh, and will seemingly linger for a long time. “If you wanna break my cold, cold heart,” Swift explains. “Just say, ‘I loved you the way that you were.’ If you wanna tear my world apart, just say you’ve always wondered.”

Swift, as an artist, is not one to “experiment” exactly, or to push her sound into places that are totally uncharacteristic, though I would argue that there are certainly moments on Evermore that are more dissonant or noisier, and there were a number of production elements on Midnights that were a little unexpected or pushed her sound out just a little further. And there is not a lot of experimentation or pushing against boundaries on Tortured Poets—again, a number of elements have such a familiar, or similar feeling to them, so more than anything there is a sort of comfort that runs through a good portion of the album.

But.

There are also a few places where there are interesting arrangements—and I am thinking, specifically here, of vocal arrangements and melodies that are a surprise, and do assist in drawing more attention to a song. The higher register, eerie echoing of the titular phrase that opens “So Long, London” is one moment—it’s haunting, and fragile in its beauty, and is not indicative of the song to come, but does captivate even for the few moments it is present.

Another moment is the juxtaposition of playful and sad that is struck in “I Look In People’s Windows,” which is another one of the additional tracks found in the expanded edition of the album; it is also one of the few songs from the second set that includes production credits by Antonoff, and he and Swift are joined by Patrik Berger, who has worked with Swift in the past but also has credits for songs like Icona Pop’s blown out “I Love It,” Lana Del Rey’s “Off To The Races,” and Robyn’s classic “Dancing On My Own.”

“People’s Windows” does not reach the bombastic or cathartic heights of those aforementioned songs—it says in a quiet place of reserve, with Swift kind of skipping along the sparse rhythm that’s created from very few, but extremely effective elements, including a hypnotic bit of string plucks on a tight sounding acoustic guitar—so precise in how it sounds, each time, and the feeling it has, that it almost seems like a loop built around the riff being played a single time, accompanied by subtle flicks of the strings of the cello, and oscillating synthetic atmospherics.

And there is of course the juxtaposition of the playful and sad nature of it all, but there is also collision that occurs between the organic warmth of the guitar and the cello, with the ripple of other noises cutting through, and the metallic, icy vocal effects that trail off of Swift as she sings.

The playful melody within the song arrives early on—“I had died the tiniest death,” she begins in the opening line. “I spied the catch in your breath,” she continues, before repeating the word “Out” six times—each with a slightly different emphasis in order to stretch this to the next line. “Northbound, I got carried away—as you boarded your train.” This melody returns, with the word “South” this time, and she does reintroduce it in both the chorus, albeit a little abbreviated, in part of the line, “What if your eyes looked up and met mine one more time,” and again in the song’s second verse.

For a song that does have such skeletal arranging, and is the album’s shortest track (just barely over two minutes), Swift does give us a lot to think about with the very idea of looking in people’s windows, among other themes that she mentions, seemingly as an aside, near the end of the song.

“I look in people’s windows,” she boldly declares in the chorus. “Transfixed by rose golden glows,” which is both a very poetic, and also a very accurate way to describe the feeling. Because. Have you, reader, ever been walking through a neighborhood—either your own, or a neighborhood you are simply visiting, or passing through, and caught a glimpse of the life happening that is framed by a living room window? Have you perhaps wondered what is on the television?

Have you tried to slyly look at their furniture, or attempt to make out what books are on a shelf?

Have you been unable to advert your gaze as you try to continue your walk, but find yourself imagining this life that is not your own.

The glow coming from the window, out onto the sidewalk, rose golden.

“I look in people’s windows in case you’re at their table,” Swift explains. “What if your eyes looked up and met mine one more time?”

Lyrically, throughout her career, as it has continued to grow, and as her mythology and lore build with literally every move she makes, it is apparent that nothing Swift does is coincidental. More than likely, what she does, in terms of promoting a record, and even within the songwriting itself, is done deliberately and with intention.

And what is, perhaps, more interesting to me—just slightly, though, because the concept of peering into the windows of strangers is utterly fascinating to me—is a line that not a lot of time is spent on within the final verse. “I tried searching faces on the street,” Swift explains. “What are the chances you’d be downtown?”

And, perhaps, this is a bit of a reach, or a stretch. Or, perhaps it is just simply a coincidence, though that seems unlikely even. And I tell you all of that to tell you this—there are a number of lyrics from the opening song on The National’s Laugh Track, “Alphabet City,” that I regularly think about since hearing it late last summer, but there is one in particular, that comes alongside an idea, or a concept, that I find myself returning to often. “Sometimes I want to drive around and find you,” the band’s frontman, Matt Berninger, sings in his low, rumbling baritone. “And act like it’s a random thing. I always wonder if you ever feel like I blew all chances of this happening.”

This line is, apparently, based on something that Bryce Dessner—brother of Aaron and someone who contributes orchestral arrangements to a few tracks on Tortured Poets- does. Or at least used to do. That if he has the urge to seek someone out, and physically look for them. And if he does find them, he will act like it is a coincidence, or chance, rather than something he had intentionally set out to do.

And, for me, there is too much of a connection here to be ignored, between Berninger’s lyric, and Swift’s in “I Look In People’s Windows.”

“I tried searching faces on the street. What are the chances you’d be downtown,” she asks.

Swift, in the final run of the chorus of the song, refers to herself as a “deranged weirdo” for her penchant for looking in people’s windows. I disagree—though a line like that does lean into slightly taboo or at least the unsavory nature of the practice. She doesn’t really acknowledge it, or explore it, but in both this idea, as well as the one of attempting to manifest an encounter with someone, there is a desperation of sorts that is unsettling, yes, but also surprisingly beautiful, and if anything, it is something that I, and perhaps you do too, understand.

*

Am I allowed to cry?

And we have reached that point. Or, we are on the cusp. Where I, with what I hope was care and attention, have talked about certain songs, and certain elements of The Tortured Poets Department, but have, as I so often do, my favorite, or what I have deemed to be the most impactful tracks for the end, before I attempt, as I so often do, to drag all of these words on the page towards a conclusion.

With the excess that does, truthfully, weigh down the album and create a real barrier that prevents a casual listen, it was not difficult to, in the time that I have spent with Tortured Poets, over the last few weeks, determine which songs would arrive with me here, near the end—but rather, it was, as it so often is, difficult to figure out how to write about them with tact and grace, to detail why these are the songs that, for me, are the album’s finest moments.

I joked that, around a week after Tortured Poets had been released, my takeaway from the album was if I were to send someone—regardless of whether I was romantically involved with them or not—a song by The Blue Nile, it would not be “Downtown Lights.”

And, yes, okay. Maybe it is the honestly surprising reference to The Blue Nile woven into the opening line of “Guilty as Sin?” that initially lured me into the song—but what I have come to understand in the weeks that followed, and in my listens through the album, is that “Guilty as Sin?” (yes, the title is stylized with the question mark) is one of the most accessible songs on the album, and is certainly one of the more straightforward in its structure.

It is also built around something that I think Swift is really good at, but something that she does not explore very often in terms of tempo and arranging, and that is the mid-tempo slink.

I am remiss to say that Swift, as a songwriter and performer cannot be sultry, or sensual, because she can be—and she has done it in the past, I think, with some success. But she’s also very self-aware, and perhaps at times with that self-awareness, she can be sillier than anything else.

“Guilty as Sin?,” though, works because there is a kind of effortless sensuality to it, which, like the reference to a song from The Blue Nile’s second album, Hats, is a surprise. But it works. Like, she does really commit to this smolder that the song finds itself within almost from the moment it begins, and the way she carries herself in the lyrics—a longing, a little lusty, a little melancholic—only helps it burn as slowly, and as powerfully as it does.

And there is a part of me that wonders if Swift and Antonoff (who are credited as producers on the song) could have tried to tastefully interpolate a little more of The Blue Nile song referenced—it is one of the more shimmery and uptempo songs on Hats, but there is another part of me—the more analytical listener, that is glad that they played against the urge if it was even there, and instead, craft a kind of downcast tone with moody synths set against a clattering drum machine beat when the song opens, before it continues to build, with ease, into the dazzling, soaring chorus.

It soars, yes, but even in the, like, borderline triumph of the moments when Swift guides us to the surprisingly lusty question she asks at the beginning of each chorus, there is still this sense of emotional restlessness, longing, and of course, a terrible kind of melancholy.

The arranging in the song, and the slower tempo it is given, and the way it lifts itself up just enough when it counts, are all certainly things that contribute to just how accessible of a listen it is, but it is also a vocal melody that Swift makes use of throughout the song—one that is not familiar or similar to things from the past, which, I think, is another reason the song is such a standout. She introduces it near the beginning—“Drowning in The Blue Nile,” she sings. “He sent me ‘Downtown Lights’—I hadn’t heard it in a while.” And it’s the way she finds a natural rise and fall to “lights” that she will then hit a few lines later, and then in the chorus, where it is the most effective.

“What if he’s written ‘mine’ on my upper thigh only in my mind,” she asks with a surprising bluntness. “One slip and fallen’ back into the hedge maze—oh, what a way to die.” And from there, she she continues to push herself into this surprisingly sensual place. “My bedsheets are ablaze—I’ve screamed his name. Building up like waves, crashing over my grave. Without ever touching his skin,” she asks. “How can I be guilty as sin?”

The song’s one fault—there is, unfortunately, just the one, is the bridge. It does, intentionally so, bring the song to a crawl, and is littered with just a little too much religious/messianic imagery (something that is found throughout the album.) But. When the song kicks back in for the final chorus, which includes the line, “Messy top-lip kiss, how I long for our trysts,” Swift asks the question found in the title. But for me, at least, a more pressing question, or one that is more relatable, is the one she bookends the song with, after mentioning “Downtown Lights.”

Neither question receives an answer. But she asks, pensively, “Am I allowed to cry?”

Because, again, with the intentionality of Swift’s writing, there are, of course, layers to that question—two, for sure. The first and most obvious is the kind of longing, or emotional resonance, that comes in from the reflection on this relationship—the song, I don’t think, attempts to hide the fact that it is about Matt Healy, who has stated, The Blue Nile is his favorite band, and he sampled “Downtown Lights” in a song with The 1975, apparently.

The resonance, and longing, that comes with hearing this song, and thinking about the way they all intersect and wondering if there is an allowance for tears when everything converges.

But there is more to the line, I think. Something that adds more heft to it. And that is a kind of breaking of the fourth wall between Swift and the listeners, and removing the idea of person and persona, and her questioning if she is truly allowed to show this kind of human emotion, or have this reaction as a result of this tumultuous and very public relationship, and subsequent breakup.

Am I allowed to cry?

*

Admittedly, I was surprised at just how many of the songs on this album, across all 31, are seemingly about her short-lived courtship with Healy. Though, based on the title The Tortured Poets Department alone, maybe I should have expected their relationship and its demise would provide her the fodder she needed.

Not every song is about him. And while there is an attempt to disguise the antagonist in places, or for Swift to potentially downplay just how much of herself she is writing about, as opposed to a story, or playing a character, but there are also moments where it is very obvious who the object of either her affection, or admiration, or her vitriol is.

Placed near the end of the standard version of The Tortured Poets Department, “The Smallest Man Who Ever Lived” is, without question, one of the angriest and most pointed songs Swift has written about the aftermath of a relationship’s end. Dragging her former partners is not new territory for her (see “Dear John,” or “All Too Well,” or most recently, “Would’ve, Should’ve Could’ve”), but this is the first time she is doing it with a kind of seething resentment through clenched, gritted teeth, all of it devastating and chilling to hear unfold.

The anguish begins within the first line of the song, and the anguish gives way, quickly, to the depiction of something bleak, and honestly, pretty sad. “Who the fuck was that guy?,” Swift snaps. “You tried to buy some pills from a friend of friends of mine. They just ghosted you—now you know what it feels like.”

“Smallest Man,” before it reaches its stunning climatic moment, is surprising lyrically, in that it does find Swift at least acknowledging that her involvement with Healy became a source of contention and disappointment for a number of her fans—if not contention and disappointment, at least confusion. “I don’t even want you back,” she laments in the chorus. “I just want to know if rusting my sparkling summer was the goal. And I don’t miss what we had, but could someone give a message to the smallest man who ever lived?”

The song itself begins with a telling, seemingly exasperated, contemplative sigh from Swift before the sound of a swaying, quiet piano melody begins. With production and co-writing credits attributed to Aaron Dessner, the structure of the song itself is a fascinating one in the way Swift lets the words tumble out, just at the right time, into the delicate rhythm that’s forming, but there is a kind of fragile looseness to it, at least within the first lines, before a subtle synthesizer blip and quickly paced drum machine beat comes shuffling in underneath to create just a little more direction.

The verses to “Smallest Man” are dedicated to a kind of embittered reflection—the things one wishes they could say, or could have said, before the relationship came to an end, or the kind of things you only realize well after things are over. “In public showed me off, then sank into stoned oblivion,” she reflects with regret. “‘Cause once your queen had come, you’d treat her like an also-ran.”

With the way the song simmers in such a place of sadness and tension, the way it explodes should really not have been a surprise to me. But it was. It was, like, the most surprising and perhaps the most impressive moment on the album—the way everything just fucking detonates all at once, beginning with a swelling of the string arrangements by Rob Moose after the second chorus, and a huge inhale from Swift, who rushes into the bridge, with a noticeable distorted, blown out effect on her voice, as she asks, “Were you sent by someone who wanted me dead? Did you sleep with a gun underneath our bed? Were you writing a book? Were you a sleeper cell spy?,” demanding answers, with real, honest rage and contempt in the way she delivered each line as the music behind her continues to thunder, with enormous, ringing piano chords, gigantic electric guitar strums, and pummeling hits of percussion.

Swift continues with the religious imagery in the bridge on “Smallest Man,” though this occurrence is one of the times when it actually works and isn’t overextended, as she is just absolutely unrelenting in her attack. “I would have died for your sins, instead, I just died inside. You deserve prison, but you won’t get time,” she sneers. “You’ll slide into inboxes and slip through the bars—you crash my party in your rental car. You said normal girls were boring, but you were gone by the morning. You kicked out the stage lights,” she concludes. “But you’re still performing.”

And, perhaps, more impactful, and more resonant, than this cacophony that swallows the song, and rightfully so, is the way it just ends. Swift fires one more shot, as the music begins to resolve around her, and it concludes. Quickly. Not rushed, though. Because there is, like, no way for her to top that explosion or bring the song into a final chorus or a key change. The wall of noise collapses around her, and she’s left standing. Angry and heartbroken. A terrifying and show-stopping moment on the album—a flash of brilliance and cantharis that, even if briefly, reminds us of why we continue to listen to Swift and why we, or at least I have spent so much time with The Tortured Poets Department. Because even when it runs long, there are still these places of harrowing power.

*

The story isn’t mine anymore

And we have arrived at that point, now, haven’t we, reader. The part of these essays that are, of course, about an album, but often are about much more than that, where I am supposed to draw some kind of short, but poignant conclusion from my time spent sitting with and analyzing the record in question—the music itself, of course, and the artist responsible, but I often feel compelled, or find, that I am learning something about myself, or how much of myself I see in the music.

I often—and yes, of course, I am aware that I do this, will refer to difficult questions asked by the album with no easy answers provided.

I often, perhaps too often for it to hold the merit it once might have, refer to the record in question as an allegory or a reflection on the human condition.

The Tortured Poets Department is not that kind of a record.

The album asks questions, certainly, but more than anything, it asks too much of its listener.

It’s easy to simply say that 31 songs is a lot of songs for a listener—a casual fan or a diehard—to sit with and have the patience and care for. And it’s easy to say that when the album does, in the end, completely buckle under the weight of its sky-high ambitions and rollout, that somewhere in there, there are songs that work, or are more accessible, or more palatable, and that Swift could, if she were so inclined, self-edit, and have paired this album down to a much more manageable amount of songs (a dozen? 14 at most?) and have come away with a much more concise and less intimidating experience.

There is more to it than that, though. Than just the songs. That there are too many and some of them are just not that memorable or enjoyable.

It’s easy for me to avoid certain corners of the internet, because I know that I do not belong there, and do not feel compelled to spend time in them. But there are places where an album like Tortured Poets is a topic of speculation—specifically, if there are hidden, or at least well-buried meanings and intention behind some of these songs.

Is the country-adjacent and grandiose “Daddy, I Love Him” not the story song that it actually appears to be on the surface, but is a very sly “fuck you” to her fans for their disapproval of her relationship with Matt Healy?

Is the spooky, sweeping, and cinematic “Who’s Afraid of Little Old Me?” really about her alleged, ongoing feud with Olivia Rodrigo?

Does this matter to you, as a listener? Do you believe it? Does it matter to me? Does it inform how I feel about the album?

How much of the mythology and lore surrounding Swift to you buy into, or take into consideration? How much of this lore and mythology do you think Swift herself buys into?

Tortured Poets might be good, or fine, and just like too long and uneven, of an album, but the length and commitment needing to be made to it is not the only barrier to my experience with the album.

There is the idea of Taylor Swift. She’s an artist. She’s a singer and a songwriter. A performer. An entertainer. A businesswoman. A brand. And she, as best as she can—she is not perfect—has tried, especially in recent years, to find the balance between the person and the persona.

We love the art. We appreciate the art. Can we reconcile with the artist who makes it.

Taylor Allison Swift is a person. There is the persona she projects, or wishes to be perceived as. Those things end up converging in on one another. We love the art. We appreciate the art. How forgiving can we be, or how critical can we try not to be, at what are missteps—the enormous platform she has, yet she remains silent on enormous, and important issues.

We love the art. We appreciate the art. We want to appreciate the artist. But it becomes hard to defend when she is the butt of countless jokes at the expense of the use of her private jet, and the billion she is apparently now worth.

We want to reconcile with the artist, but it becomes hard when they become romantically involved with someone we question.

We want to reconcile with the artist, but it is exhausting when everything—every literal move becomes monetized, and then monetized again.

There is the idea of Taylor Swift. She’s an artist. She’s a singer and a songwriter. A performer. An entertainer. A businesswoman. A brand. But she is also a person. Is she allowed to cry? I would say yes, but I do not know if she will allow herself to do so in an effort to maintain the seemingly unending facade of the persona.

How much sad do I think she has in her? I wish I knew. I don’t think she’ll ever tell us. Because there is this projection. Someone who wishes to be seen as affable or grateful, and ultimately human but does have to, like, calculate every move and consider an image.

The Tortured Poets Department—both the 31-track expanded version, as well as one of the four iterations available in physical forms, concludes with the song “The Manuscript,” which, if anything, serves as an epilogue to the album’s themes, but it also speaks to something else—a little larger, or more personal. It’s one of the more self-aware songs in the collection, but it is done so with a thoughtful kind of grace, so Swift, in writing about herself as a very famous pop star, is not as cloying as it might come off elsewhere.

A reflection not on where she came from, but on a specific (albeit ambitiously written about) relationship’s end, blurred with other observations from the past that she looks at now with more than a little remorse and shame, it does, if there can be one, in the end, a kind of thesis statement for the album as a whole. “Looking backward might be the only way to move forward,” she says on the bridge. “The actors were hitting their marks, and the slow dance was alight with the sparks. And the tears fell in synchronicity with the score. And at least, she knew what the agony had been for.”

It ends with a line that implies, as much as Swift is able to, wishes to understand how to move forward, or look beyond. “Now and then I re-read the manuscript,” she explains. “But the story isn’t mine anymore.”

In her announcement of the expanded version of the album, she ended it by saying, “The story isn’t mine anymore—it’s all yours.” Which is cute, and all, and endearing to say to her fans, but the story, ultimately, does remain hers.

Doesn’t it.

I mean I don’t know if it was ever, really, going to be ours. It’s always going to be Taylor Swift’s story, and we, as listeners, continue to read along and sometimes just trying to keep up with the pace she’s moving at—looking to reconcile, looking to be captivated, or be moved.

We continue to look for the allowance to cry even if Swift does not show that kind of kindness to herself.

1 - Okay, so, like a footnote here is not really the time nor the place to address the problems I have with the way mental health is addressed in contemporary popular music. But, as someone who is sensitive to that—perhaps too sensitive, so might say, it is like really unfortunate and kind of gross. The way that Swift talks about suicide in this song. She, also, like literally so many others, liberally uses the word “crazy,” which is so troubling. But again. Not the time or place. Just something I would love if more people were aware of.