Put That Song On, The One We Love That Makes Us Sad — Albums in 2023

The introduction I write for this—this year end thing, each year, ends up being the same, every time. I will talk about how many new releases within a calendar year I was able to successfully write about—this year it was 21.

I will lament about how with each year that passes, and now as I am closing up the tenth year of writing about music, and publishing things on Anhedonic Headphones, every December, that number is a little smaller.

I will try to articulate that the amount of pieces about new releases in a given year is not reflective of how much new music I did listen to—it is reflective of both how many albums ultimately spoke to me in some way, or that I felt compelled to write about, as well as where I am at personally.

I will give a gentle reminder that for every album that I do successfully write something about, regardless of it is for this site, or for elsewhere, that there are a handful of others, every month, that I wish to write about, but am unable to for myriad reasons.

I will reiterate the way I think about contemporary popular music, the way I write about it, or want to write about, and the way I write overall, now, has changed drastically over the last four years, and it makes prolificacy for the sake “content generation,” or whatever, difficult if not impossible. I will use words like exhausting, and phrases like time consuming.

I will use words. I use too many words, I’m sure.

I will remind that poor mental health, jobs, and household responsibilities, all contribute to the give and take of how much I would like to be doing, or writing about, and how much I am realistically able to.

A list of albums, at year’s end, provides the chance to reflect on what I listened to over the span of roughly 11 months, and identify the reasons that I found myself to specific things, or what was most representative of a moment, or what spoke to me—and continues to speak to me, still, months after I originally sat down to listen.

And given all of the factors that play roles in what I am realistically able to do as someone who writes about music on the internet, a list of album’s at year’s end, provides the chance to reflect on albums that I enjoyed, but was unable to find the time and the capacity to write about during the month of their release.

The introduction I write for this—this year end thing, each year, ends up being the same, every time, and I will, usually briefly, make mention of the liberties I take, each year, with the idea of a year end list. I am no longer interested in numerically ranking ten individual albums. This year, much like last year, and the year prior, begins with the top three—the “best” or my absolute favorites, followed by seven additional entries, in alphabetical order.

Maple Glider - I Get Into Trouble

Writing about music, specifically the way I have opted to write about music over the last four years, is not easy. It is truly exhausting sometimes. And writing about some of that music again, at the end of the year, presents a challenge, because you want to sound sincere, and not like you are simply repeating all of the things you may have said before.

And for as challenging as it is, and the kind of give and take in terms of genuine interest or passion, and what can border on becoming or feeling apathetic while you sit with your fingers on the keyboard, to make the time, and the space, to reflect on the albums that I listened to in a calendar year and enjoyed enough, or was moved enough by, to write about them—in many cases write about them a second time, albeit in a way that is not as lengthy or complicated—this does present the chance to think about growth—like, how has the album in question grown along with me as the months progressed?

Have my feelings changed about it? And if so—how have they changed?

Is that change good or bad?

Writing about music is not easy. It is truly exhausting sometimes, and writing bout some of that music again at the end of the year presents a challenge because you want to sound sincere, and not like you are simply repeating all of the things you may have said before.

I Get Into Trouble, the second full-length released from Tori Zietsch’s indie folk adjacent Maple Glider, was released in mid-October, and even before my initial listen of it was complete, I was so stunned by it—all of its delicate, haunting beauty and the harrowing bleakness it often depicts within the songs found within—that I knew it would be my absolute favorite record of 2023, without question.

And in figuring out which albums to write about with the remainder of October and the entirety of November, I knew that I needed to dedicate a lot of time to sit with and really live inside the world of I Get Into Trouble, and I knew that I wanted it to be the last “new” album that I wrote about before I began reflecting in the final month of the year.

The thing about I Get Into Trouble is that even after two months and change since I first heard it, even though I know what’s coming, it never fails to surprise me with just how incredible of a listen, and an experience, it is, and how gracefully and thoughtful Zietsch works through the horrific traumas that she alludes to throughout the album.

And there is a lot to try and unpack, in a relatively short amount of time—as Zietsch, in the record’s first two songs, “Do You” and “Dinah,” works through her religious upbringing, and what that does to a person, as an adult, and as they develop, once they try to get out from under it. She goes into, perhaps, the most vivid details in the bouncing, clever “Dinah,” where, in the chorus, Zietsch sings, “I’ve been in the church making sure no one’s looking up my skirt—but I do not feel safe here”; and when the rolling, rollicking melody returns near the end of the song, she’s altered the lyrics slightly to heighten the sense of unease: “I’ve been in the church but the church is in my skirt—and the skirt defines my worth in the church.”

I think the thing that, the longer I spent time with I Get Into Trouble that, I admired the most about it was the hyper-literate way Zietsch had written these songs, and the techniques she has used in creating extraordinarily vivid portraits by only using a small amount of words, or phrases, within the boundaries of something that is three to four minutes in length. She is the most direct, or at least leaves less to the imagination, when she writes about the slow decline of a relationship, which is the focus of the swirling and nearly psychedelic “Two Years,” the dissonant and glassine “FOMO,” and my favorite song on the record (and among the saddest) “For You And All The Songs We Loved Before,” which finds Zietsch in a last gasp of a slow dance with a partner she fell out of love with long ago, unable to leave, but incapable of seeing a future with.

“And you’ve said that you don’t like it when I make plans,” she sings, mournfully, over a slow rhythm that has just the slightest hint of a melancholic twang in it, “So put that song on—the one we love that makes us sad,” she continues, resigning herself. “I’ll pretend I’m not going anywhere.”

And perhaps it is for the best, or for the sake of the listener that throughout I Get Into Trouble, Zietsch is less direct and much more ambiguous, intentionally so, in how she writes through the trauma she depicts in some of the album’s most stirring, and affecting moments, like the howling centerpiece, “Don’t Kiss Me,” where she repeats the expression, “Sometimes my own body doesn’t feel like my body but definitely don’t kiss me,” but rather than finding comfort in the repetition, it creates a state of unease, as she explains, “My safety should not have to be earned. I was just a baby until you made me a lesson to be learned.”

The darkest song, lyrically, and musically, one that walks a line between a kind of creeping sense of dread and sounding warm and inviting, is the penultimate “Surprises,” where, over delicate and swirling acoustic guitar string plucks, Zietsch does walk us up to the edge of something unspeakable—and in doing so, does let our imaginations run with what details she is willing to provide. “I wonder if you knew what you were going to do?,” she asks of an off-stage character she expressly wishes she had never encountered. “Surprises work like they should,” she sings in the chorus. “You got me real good—you took something that you could not give back again.”

It isn’t all trauma, or relationships that are beyond salvaging on I Get Into Trouble—there are a few small glimmers of hope, though again, through her songwriting, Zietsch manages to blur the past and present into something difficult to recognize, exactly, on the gorgeous “You At The Top of The Driveway,” which is in part about, and in full dedicated to, her niece, though the beautiful sentimentality of the song’s opening lines, “Every time we talk, I don’t want to hear the end of it. Months that follow, I’ll be hanging on to the words,” are applicable to more than just a blood relative.

I Get Into Trouble is not a hopeless album by any means, but it is not one that is full of hope, either. It is simply real—unflinching in its honesty and narrative exploration of Zietsch’s life, it is put together so well in terms of arranging and production that it, at no point, is inaccessible to the ears, even when it reaches its darkest, lowest moments. Less of an opportunity for self-reflection while we listen, it is Zietsch’s memories and experiences that she is recounting, and we should consider ourselves fortunate enough to be present for them all.

Romy - Mid Air

Are you emotional? Do you want to dance?

Romy Madley Croft asks these two questions of us, as listeners, written out in huge pink letters, in the liner notes of her debut solo album, Mid Air. And I suppose that they are asked, or we should ask them of ourselves, in preparation for listening to the album—regardless of whether it is the very first time we’re hearing it or if it, since its release in September, has become something we return to often.

And the answer, at least for me, is certainly always a yes to the first, and almost always a yes to the second.

“Emotional,” though, as a descriptor, is a little ambiguous—that is the point, I think. And maybe you, like me, heard it, or think about it, and at first, perhaps you associate it with being upset or extremely sad. Or, maybe, rather than one or two specific emotions, you hear the word “emotional” and think of an individual who often struggles with finding the balance between extremes—big and often exhausting, sometimes unpredictable highs and lows.

An individual who often struggles, then, with knowing what to do when finding themselves in those extremes.

But being “emotional” does not, necessarily, have to mean something…and I am remiss to say “bad,” but it does not necessarily have to mean, or imply sadness, or being upset, or finding yourself in the space created by big, exhausting, unpredictable highs and lows.

Emotional, in some cases, could mean—or, with Mid Air specifically, does mean, a kind of tenderness. A sentimentality.

The space that forms in the convergence between yes, a kind of melancholy, but also, and maybe somewhat surprisingly, lust.

An easy way, or at least maybe an accessible way, to frame Mid Air is that it is a love letter—but within that framing, there are layers. Musically, it is a love letter to the sound, and aesthetic, from another era, with nearly every song on the album owing much in terms of production and arranging, to queer dance-club-oriented pop from the 1990s and into the first part of the 2000s.

The co-front person of the late 2000s moody, textured indie rock trio The XX—her aesthetics as a solo artist are much more kaleidoscopic and propulsive in comparison with the material from Mid Air, with nearly all of the songs included strutted around infectious, airy, and unrelenting rhythms. It’s certainly an homage to a sound from the past, but it also, in 2023, is so dazzling and jubilant that it sounds startlingly refreshing.

Are you emotional? Do you want to dance?

Lyrically, too, Mid Air, or at least a majority of it, is a literal love letter—the lived experiences and the observations, both big and small, from Madley Croft’s relationship with her partner, which, given her demure vocal delivery and the balance of lust and melancholy, all set against the backdrop of often bright, energetic musical textures, create an absolutely fascinating juxtaposition that she carries from song to song with a quiet, sly charisma.

In the way that it is structured, Mid Air is an album that I think is intended to be played uninterrupted from beginning to end—there is, the further along you go into it, a very natural rise and fall that it follows sequentially before it does arrive at its conclusion—the triumphant back to back placement of the towering, disco-infused rhythms of “Enjoy Your Life,” and the erotic joy of its shimmering closing track, “She’s On My Mind,” which includes the surprisingly lusty lyric, delivered without a smirk of irony, “She’s on my mind but I wish she was under me.”

And I am remiss to say that Madley Croft front loads Mid Air with its best, or most accessible material at the top, but it is assembled in such a way that subjectively, its two finest, or at least the most fun songs of the set are found as the record begins—“Loveher,” which is an introduction of sorts to the album, and the world built within. A quickly paced but skittering rhythm does make way for the very 90s, club-ready keyboard sound that twinkles and builds throughout as the music begins to swirl, as we are lured out into the darkness of the dance floor, Madley Croft sings gently, though thoughtfully, about her partner. “Hold my hand under the table,” she coos. “It’s not that I’m not proud in the company of strangers—it’s just some things are for us.”

The glitchy, writhing “Weightless,” is another early standout—in the way that there is a sense of tension and release, albeit a slight one, in the production, and how it continues to spiral around, though never really reaches a place where it risks becoming too much, or getting away from the hands of Madley Croft or her producers, Stuart Price and Fred Gibson; and lyrically, it does continue the kind of delicate intimacy that she sings about in “Loveher”—“I was at a party, and she was at home,” Madley Croft explains with a romantic sense of urgency in her voice as the music swells around her. “All I really wanted was to be with her alone—it’s better with her arms around me.”

Are you emotional? Do you want to dance?

And yes, there is a convergence of those two things—high emotions and the urge to move your body in time with the rhythm that occurs throughout Mid Air, but there are also moments where the album focuses on one much more than the other.

And what I have, perhaps a little slower than maybe I should have, learned, and tried to be more understanding and accepting of, is that not everything within contemporary popular music needs to be taken so seriously. Serious music—somber, depressing, vivid lyrics with layers of meanings that all are begging to be critically analyzed and poured over by some depressed middle-aged individual such as myself—is certainly what I gravitate toward listening to, but I understand that there are songs in the world, and artists out there, making music that is all about the vibe, and the vibe alone.

And the vibe, or the desire to have fun, and the encouragement and implication that us, as listeners, should be having fun too, is where a lot of Mid Air operates from, and in doing so, it is just an unabashed joy to experience and hear—like the big, open swooshing rhythms and pitch-shifted vocals of “One Last Try,” or the jittery, effervescent synthesizer ripples and earnest messaging of the midway point’s “Strong,” where Madley Croft acts like the most supportive or assuring person in your life—“Let me be someone you can lean on,” she implores within the first verse. “I’m right here—you don’t have to be so strong.”

With an album like Mid Air—on that does have a lot of heart, and a lot of thought within, but is also so firmly rooted in just wanting to have fun, and for someone like myself, who is a self-described extremely depressed individual, my love for this album is a bit like playing against type, or is perhaps unexpected.

Especially when you consider the title of the bombastic and glittering penultimate track—“Enjoy Your Life,” which is something I rarely, if ever, do, though Madley Croft certainly wants me to take the idea under advisement, and with how utterly fun this album is, she does make a very compelling argument.

Are you emotional? Do you want to dance?

Romy Madley Croft asks these two questions of us, written out in huge pink letters, in the liner notes of her debut solo album, Mid Air. And the answer, at least for me, is certainly always a yes to the first, and almost always a yes to the second.

Because there is something incredibly alluring about it all, isn’t there? Alluring and comforting. And I think that is what I found so compelling, and ultimately so welcoming about Mid Air. Yes, it can be melancholic, at times, and extremely earnest and sentimental, but that fragility is deftly balanced with moments of transcendental bliss and meticulous production detail on every track.

Am I emotional? Do I want to dance?

There is something incredibly alluring about it all, isn’t there? Alluring and comforting at the idea of losing yourself for a few moments—just letting go completely, and not only listening to these songs, and the messaging behind them, but really feeling them within your body and allowing yourself the chance to feel good for once.

Or to feel hopeful.

Or to have fun.

You don’t have to be so strong. And for, like, 30 minutes and change, Romy Madely Croft is enjoying her life openly and wants you to enjoy your life too.

Angie McMahon - Light, Dark, Light Again

Light. Dark. Light again.

Angie McMahon repeats these words—the titular phrase of her sophomore album, like an incantation, near the end of its explosive closing track, “Making It Through.” And, I mean, just taken at face value, the sequence makes sense, and can appear quite literal in how it could, and maybe does, in part, describe the beginning, the ending, and the start of a new day.

Light. Dark. Light again.

And this becomes very clear within, like, the first song on the album, but that sequence is intended, mostly, to be looked at figuratively as a reflection of ourselves. We are light. We can be dark. We can be light again.

It takes effort, though, to find your way back into the light.

Light, Dark, Light Again, arriving four years after McMahon’s blistering full-length debut, Salt, is a marvel in its meticulous attention to production—intricate, with songs often crafted around incredibly dense, warm layers of sound, and lyrically, McMahon’s writing comes from a place of deep self-reflection—contemplative and clever, but also, in its brutal honesty, can be quite difficult to hear as she regularly faces herself and her shortcomings, and then requests you do the exact same.

And the demands that self-discovery and self-improvement put on one can be rather intimidating, or daunting, but the thing that is so impressive about Light, Dark, is how, even with all the work that must be done, and in making eye contact with all the difficult things, it is an album throughout, and especially as it concludes, is full of a surprising kind of hope, or optimism.

In the delicate, then stirring opening track, which serves as a prologue to the album as a whole, “Saturn Returning,” McMahon makes the first of a number of pledges, or promises to herself—assurances she says throughout the record about what she wants, and in saying them out loud, there is an understanding of the amount of effort that goes into keeping those promises.

“I’m gonna love every inch of this body,” she exclaims as the song begins to build, and before she arrives at another one of the more prominent themes present in a number of songs on Light, Dark—which is the idea of surrender.

Surrendering to yourself, yes, but also to something much larger, and perhaps unknown. But that in doing so, you trust that there is something out there for you.

“Please, always catch me the way that you caught me,” she sings, her voice soaring as the music continues to swell toward a crescendo.

And what is impressive, and most impactful, about Light, Dark, Light Again, and the way McMahon presents her journey into self-discovery and self-improvement, is yes, certainly, the optimism and hope that is imperative to reaching this place, but not every song on the album is optimistic or hopeful—there is a tonal dynamism that is fascinating, as she balances on the line between the desire for something more significant, and the pathos that brought her to the place where she understood what, within, needed to change.

Sometimes the sorrow is found within just a line or two, like the stark chorus to “Divine Fault Line”—“You’re on your own dark side of the border tonight—and you’re all fucked up, and you’re wanting to die,” she howls while the thuds of the percussion and cavernous piano chords swirl around her. And other times, the sorrow is the entire song, like the stunning “Fireball Whiskey”

—the album’s second track, and one of the singles released in advance of the album’s arrival in full, which details, rather graphically at times, the difficulties of realizing you are no longer in love with someone, and the process of having to let go.

And it is within “Fireball Whiskey,” where McMahon delivers one of the most affecting lyrics of the entire album, and perhaps one of the most harrowing of the entire year. “This morning I did not want to get out of the shower, but hot water runs out, and you have to carry on, don’t you?”

The conceit of Light, Dark, Light Again is the self, but within that, there are moments where McMahon deviates, and as the record winds down, one of the earliest written songs for it, the jazzy, stuttering “Staying Down Low,” details her attempts to both help herself, while still trying to show up, and be supportive for someone else who is also struggling—and while you can make suggestions of things that can be done to pull yourself out of a depressive state, what she lands on, and what the important take away here, is respect and understanding.

“I know that you’re tired,” she confesses near the conclusion, but within the admittance of understanding someone’s exhaustion, she still wants to be encouraging, and repeats that the titular “staying down low” is no longer fitting this off-stage individual.

The idea of improving yourself, or looking within for larger discoveries, and even surrendering yourself over to something much larger and unknown—it is all difficult to wrap your head around, or make space for, even in some small regard, because, and I think this album does a good job acknowledging that it can be, and often is, difficult to do—pushing yourself to be “better” is maybe too big of an ask, and the push you give yourself is to simply get out of bed in the morning, or to not stand under the showered until the hot water is all gone, or to not cry in the driver’s seat of the car either before or after your day at work.

Sometimes, the push is existing as you are able, and what McMahon has done with Light, Dark, Light Again, and has done so with a delicate grace, is remind us that there might not be a cure for the human condition, but there are shreds of hope that we can wrap our fists around as a means of pulling ourselves, slowly, out of the darkness.

* * * * *

Boygenius - The Record

In a calendar year, there are so many different kinds of albums I find myself listening to—there are the ones that I listen to with the intent of writing a piece about and am ultimately able to follow through on that intention; there are the albums that I listen to with the intent of writing a piece about, but am ultimately, for whatever reason (there are often many) unable to follow through on that intention; and there are the records that I listen to out of curiosity—perhaps I read a positive review, or saw it mentioned somewhere on social media.

And sometimes, those are records that do end up connecting with me in some ways; in other instances, I find myself struggling to understand what someone else might see (or hear, rather) in it.

In a calendar year, there are so many different kinds of albums I find myself listening to, and within those, there are things that keep me returning to that album as the months pass, and we find ourselves at the end of December, in moments of reflection.

With some albums—pop music, specifically, it is often because I am in search of something that is more vibe-based and probably a lot more fun to listen to. With most albums though, regardless of it I am listening with the intention of writing about it, or just listening for myself, I gravitate towards the melancholic, and the kind of lyrics that lend themselves to analyzing critically.

And with the melancholic albums that I do find myself gravitating towards, and then returning to, throughout the year, it is because of either one specific song, or a handful of songs, and within those songs, there is often a key lyric that resonates the most.

It should not be surprising that The Record, the full-length debut from Boygenius, contains a number of those songs, and a number of those lyrics—ones that will stay with me well into the new year, and the years that follow. But the one that I keep returning to, as of late, that is perhaps surprising to me, is from the Phoebe Bridgers lead “Emily, I’m Sorry,” where, in the chorus, Bridgers, along with her bandmates Julien Baker and Lucy Dacus lament, “I feel myself becoming someone only you could want.”

The reemergence of Boygenius, at the beginning of the year, came as a welcome surprise, because I was, and maybe you were too, uncertain if the trio would ever reunite to write and record as a group again, given the continued rise of their respective solo careers after the initial outing under the moniker in 2018.

And I get the backlash, or at least the criticisms of The Record, or perhaps of Boygenius as a project, or an idea. I mean—I get it to the extent that I can. Or I, at least, try to understand that the album, and the group, is not for everyone, And with many of the criticisms, or the backlash, I disagree.

The thing about The Record, and it did take me a little bit of time to really figure this out, is that it both played its hand entirely too soon, in terms of its points of accessibility, and it can be, especially within the second half, be a challenging listen.

The thing about The Record is that, in that juxtaposition between accessibility and difficulty, it is the kind of album that is intended to be consumed as a whole—specifically when listening to it on vinyl, because it begins with a distended, stretching effect between the album’s intro, “Without You, Without Them,” and the first “proper” track, the blistering Julien Baker-lead “$20,” and then ends with an unnerving, fascinating, and ironic locked groove on the final word of the scathing “Letter to An Old Poet”—“Waiting.”

And The Record playing its hand entirely too soon (within its first side) isn’t necessarily a bad thing, or like a fault of how it is sequenced, and the process of rolling out the album prior to its release—the first three singles, all released at once, as well as the final advance single—the explosive, emotionally charged “Not Strong Enough,” all arrive before the halfway point, which does give, perhaps, the wrong impression of the album.

Because, yes, The Record is full of these big memorable moments, like “Not Strong Enough,” or “$20,” or the thrashing, ramshackle “Satanist,” which appears near the end of the second side—but it does also work, throughout, with a biting, dry sense of humor, which you can hear in the acoustic interlude, “Leonard Cohen,” or in the strummy, rootsy, “Cool About It.”

And, the further along the album gets, the more inward, and more somber the tone—the slow-burning, Lucy Dacus-lead “We’re In Love” is, thanks in part to the tone of Dacus’ voice, as well as the lyrics themselves, is particularly harrowing, as is the embittered and sorrowful “Letter To An Old Poet,” which in its melody and structure, surprises with a direct callback to the Phoebe Bridgers penned “Me and My Dog,” from the group’s debut EP.

The thing about The Record that is, I think, most observationally impressive, even if Boygenius, as a group, or the members of its group, individually, are not for you, is the way that the songs here are divided up in terms of which ones are more focused on a specific member, and which provide opportunities for all three to work together—i.e., songs like the slow-burning, regretful “Emily, I’m Sorry” and the gentle, sweeping “Revolution 0,” both feature Phoebe Bridgers taking the lead, and are both musically similar to the material she has released on her own, while the stirring “Not Strong Enough,” where each member takes a verse, within the way it builds, dazzles, and then takes off into something much larger than itself, is not really indicative of any one artist’s output outside of the group.

And the thing about The Record that lingers well after you get up to take the record off of the turntable and putting an abrupt end to the locked groove that continues to awkwardly play through your speakers, is that even when this album, in its writing, can take you to some extremely sad and dark places, and often asks that you confront, or at least acknowledge some very unflattering things within yourself that it very easily reflects at you, is how much unabashed fun it sounds like Bridgers, Dacus, and Baker are having—you can see it when they perform live, or in the myriad photo shoots they’ve done in promotion of the album, and you can hear it in the rich production and arranging of this album. It sounds labored over, yes, and rightfully so, but it is also the sound of three peers, and close friends, coming together to support each other, to create something new that is extraordinarily personal and completive, and at times challenging, all while have an absolute blast doing it.

The thing about The Record is that it does ultimately make a big ask of you, as a listener, but within that ask, and the patience and thoughtfulness required, there are rewards offered in return each time you listen, and rewards offered every time a moment from it, or even just a certain lyric from one of the songs, crosses your mind.

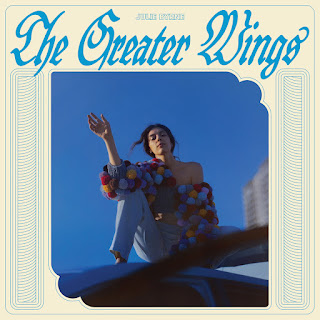

Julie Byrne - The Greater Wings

I used to, for a number of years, return to this idea that someone—at the time, a close friend—had mentioned to me in a conversation that, despite my efforts, we never really finished having. She said that there was a place where both grief and joy could co-exist. This isn’t like a new concept by any means, but it was not something that I had, in spending so much of my life with more of one of those than the other, ever given consideration to. And for a long time, I often felt like I was trying to find that space—the space where there was a balance, somehow, between those two extremes.

It seems so easy. We grieve, yes, but rather than finding yourself lost within it, you recall the moments of joy you shared with the individual who is gone, and you try to hold on, as tightly as you can, to that good, joyous feeling, rather than allowing your fingers to slip away from it, falling back down, further and further, into a kind of sadness you are either uncertain or simply just unable to process in a healthy way.

But what I realized while listening to and then writing about Julie Byrne’s stunning The Greater Wings, is that I had stopped looking for that space where those two emotions co-existed, which is funny, I guess, or at least fitting or appropriate, because the album itself is document’s Byrne’s search for that very space.

In writing about Julie Byrne, I have often referred to her as enigmatic—in part because of the long periods of time she often has gone without releasing any music. Long enough to make you wonder what became of her, or if she decided to leave performing behind. And in a sense, she sometimes has, but then finds her way back to it—between her earliest recordings, released on limited edition cassettes in 2012 (then reissued on vinyl two years later), she worked as a park ranger, and experiences, as well as her almost nomadic lifestyle at the time, helped inspire Not Even Happiness.

And the thing about The Greater Wings is that it, under different circumstances, would be more than likely be a completely different album. Byrne began working on it with her regular collaborator, at-times roommate, and at one time, romantic partner Eric Littman, who passed away unexpectedly in the summer of 2021—causing Byrne to cease working on the album entirely and shelve it for close to a year before she, like she had in the past when stepping away from music, found her way back and completed it.

As it walks the line between grief and joy, or of fond remembrance, The Greater Wings is both terribly beautiful and terribly haunting in how it sounds, and how elements of it will linger well after the album is over. Byrne’s voice has always had a rich smolder to it since the first time I heard her on a cassette over a decade ago, and that low, soothing range she often sings from is very present throughout this ten-song meditation on the intersection of love and grief, and the space that begins forming when those two things converge.

Byrne, as a performer, could and probably often is categorized as a folk singer—regularly accompanied by an acoustic guitar, and not much else, there is a quiet, rootsy, delicate nature to a bulk of her work. And yes, this kind of folk or folk-aesthetic is present throughout The Greater Wings, but it is an album where Bryne has become more comfortable, perhaps out of necessity, with the idea of floating away from the sound she is most associated with through, through the inclusion of the moody yet shimmering warm synthesizer textures, like within the bubbling and swirling “Summer Glass,” or later when she explores more a soulful but ominous sound on “Conversation is A Flow State.”

The arranging and instrumentation across The Greater Wing do lend themselves to Byrne’s reflective lyricism, which is as poetic as it is poignant in the observations she makes about herself and what it is like to exist from the deep end of grief, attempting to swim, as best as you are able, toward shallow waters, or even to shore. Her writing, as one might anticipate, as she comes face to face with her grief, is earnest—“I drank from the pitcher of life,” she exclaims on the bouncy acoustic “Portrait Of A Clear Day,” a song that ends with the album’s most outwardly sentimental line: “I get so nostalgic for you sometimes.”

Her writing is also full of a palpable, often restless kind of longing, which you can hear in the sweeping, gentle “Lighting Comes Up From The Ground,” where she coos, “I tell you know what, for so long I did not say—that if I have no right to want you, I want you anyway.”

This is no longer the case, but for a number of years, I used to return to this idea that someone, who, at the time, was a close friend, had mentioned to me in a conversation that we never finished having. She had said there was a place where both grief and joy could co-exist, and for a long time, I often felt like I was trying to find that space—the space where there was a balance, somehow, between those two extremes.

Without realizing it, or really understanding that I had done so until I sat down with The Greater Wings, I had stopped looking for that space. And maybe Byrne was not, at least up until 2021, was not looking for that space but had to find herself in, and then work her way out of it through this collection of songs.

As much a meditation on grief and joy as it is on who we love, and how we love them, The Greater Wings is a gorgeous, emotional, and thoughtful statement that, like the grief, joy, and love, remains with us as listeners long after the record has come to an end.

Carly Rae Jepsen - The Loveliest Time

Over the summer, just a few months shy from the first anniversary of her album The Loneliest Time, Carly Rae Jepsen announced the imminent arrival of its companion piece, The Loveliest Time, by saying, “At this point, you know me so well that I won’t even tease about the b-sides. It’s almost disrespectful because you know that it’s coming.”

And we, as her audience, and listeners, do know, I suppose. And there was, and is, and will continue to be, what I feel like are fine lines between what an audience, or listeners know, and what they might ultimately have come to expect, or presume, and the space where those lines might, in fact, overlap, for better or for worse.

Jepsen has traditionally, in the past, issued a collection of b-sides roughly a year after the release of the “proper” album as a means of commemoration—in 2016, it was an eight-song EP of material leftover from the Emotion writing and recording sessions; in 2020, two months into the pandemic, it was a full-length LP of more songs that were, at one time, contenders for a place on Dedicated. And in giving it a similar, but different title, The Loveliest Time is intended to both serve as a continuation or expansion of her 2022 album, and also stand on its own.

And the thing that has, since the release of Emotion certainly, made Jepsen such a fascinating songwriter and performer, is, yes, the mythology that surrounds her prolificacy (she allegedly writes upwards of 200 songs when preparing to record an album), but also the extraordinary tonal diversity she has developed, and continues to nurture with each album, which can be heard on The Loneliest Time, certainly, but is even more apparent on The Loveliest Time.

Jepsen has referred to it as a collection of her more experimental songs—and for someone like her, operating within the boundaries of “pop music,” yes, a lot of the songs featured within this collection could be seen as a little experimental, and if not experimental, a little more daring, or risky. They aren’t inaccessible by any means, but there are moments that could be considered a little more challenging, at least at first—like the surprisingly dissonant, and borderline shrill vocals on the chorus to the swaying and sultry opening track, “Anything To Be With You,” the handful of songs that make use of a jittery, frenetic pacing and production, like the dizzying rhythm of “Put It To Rest,” or the unrelenting and shimmering “After Last Night,” and the vibrant bombast of the closing track, “Stadium Love.”

The homage to, and influence of, a 1980s kind of dazzling aesthetic could be heard, and felt, throughout Emotion, but Jepsen has been stepping further away from that with each subsequent album—both on The Loneliest Time, and here, there are myriad echos and nods to the 1970s—a smoldering, slow motion haze heard on “Kollage,” and the slithering, pulsating disco-inspired production on the collection’s first single, “Shy Boy,” and then elsewhere on “So Right,” the glistening “Come Over,” and the rollicking, blown out, Daft Punk-esque “Psychedelic Switch.”

Even within the few moments that are not as immediate, though they do grow on you, or at least me, with enough listens, and even in the few moments when it does truly falter, there is such a compelling dynamism throughout The Loveliest Time that is an album strong enough, and genuinely interesting enough (albeit restless at times) to stand on its own, and continues to show why Jespen, well over a decade removed from the success of “Call Me Maybe,” remains the kind of artist who is very capable of making pop music that can be both thoughtful and unabashedly fun, often within the same breath.

The National - First Two Pages of Frankenstein / Laugh Track

The National has been, for years now, and will remain, for the foreseeable future, one of my favorite bands—my second favorite band, actually, and if I am required to put them in placing or ranking, and they are second only to Radiohead.

But even in my admittance that The National is one of my favorite bands, I am the kind of fan, and listener, who can be a fan, and continue to listen while remaining analytical, or as objective as I can, perhaps, be—my affinity for them does not require, nor does it bind me, to love, without question, every album that they release, or everything that they do.

And, when I was writing about their sprawling and dense 2019 album, I Am Easy to Find—16 tracks and just slightly over an hour in length—what I had decided was, even though there are caveats to the album that should be taken into consideration, like many of its songs being included within a short, experimental film of the same name, or that it was the first time the group worked with myriad guest vocalists, that somewhere within that hour plus, and 16 songs, there was a slightly leaner, and more cohesive album waiting to be found if just a few things things were trimmed away.

And I do ultimately feel quite similar about the two albums The National released in 2023—First Two Pages of Frankenstein, and its companion piece, or continuation, Laugh Track.

In combining both albums to 23 tracks total, there, again, is what I would consider to be a tighter album, waiting to be unearthed—one that continues building on its own momentum, and leans further into its strengths, or the band’s strengths, rather, instead of becoming weighed down or appearing sluggish in its pacing. Across both albums, there are no real “bad” songs, per se, but there are certainly moments that are less successful than others, and if you were to theoretically remove those, it would give space for all of the more impressive, poignant, and slow-burning moments to resonate just a little bit more.

And that’s the thing—even when the albums (both albums) falter, like the unhinged, inaccessible closing track to Laugh Track, “Smoke Detector,” or the slithering, “Alien,” found at the halfway point on First Two Pages, the songs are not like, unlistenable; they are just not as genuinely interesting to hear, or as thought-provoking as the band has certainly shown, over their career, they are capable of being.

Both First Two Pages of Frankenstein and Laugh Track were written and recorded during the same time period, and both albums are, lyrically, a reflection on what it took to get the band back into the studio—it has been well documented in the interview cycle leading up to Frankenstein, as well as in literally every piece of writing about both (it was unavoidable to talk about in my own reflections on the albums) that the band did almost disintegrate during the pandemic, with front-end and principal lyricist Matt Berninger slipping into a debilitating depression, coupled with a year-long bout of writer’s block.

He was convinced the band was finished, or at least that he would never regain his ability as a songwriter, and that unease and tension can be heard rippling through both records—self-doubt, self-deprecation, and sentimentality for those closest to him, and what that closeness means, have always been among the themes present in his writing, but this time, the stakes are much higher, and everything is much more fragile than it had been in the past.

I referred to Matt Berninger as a “wife guy” somewhat recently, because, in the earlier days of the band, his writing was, famously, much more abstract and dark—there are often still abstractions, sure, but he is much more personal, and literal now, and has been for certainly the last decade. And while it might be a little too saccharine or disingenuous for some listeners, as someone who does struggle with big emotions and difficulties communicating within my own marriage, something that keeps me returning to The National, and has kept them as one of my absolutely favorite active bands, is that I find his portrayals of domestic scenes to be regularly vivid and heartbreaking—and in those portraits, I often catch such unflattering and difficult, but unavoidable and accurate, glimpses of myself.

Berninger can, and often is, wistful, in moments across both albums. On one of the advance singles from Frankenstein, “New Order T-Shirt,” over a slinky, and bouncy rhythm, he recalls through evocative, fragmented details, the earliest days of his courtship with his spouse Carin Besser, who often co-writes lyrics with him. But even in the kind of jubilant, youthful nature of the song (depicting New York City, pre-September 11th, 2001), there is a melancholic or at least bittersweet nature to how he looks back: “I keep what I can of you,” he muses in the chorus. “Split-second glimpses and snapshots in time.” The mirror image, then, or at least funhouse mirror reflection of these kind of memories occurs, is represented within the absolutely stunning, smoldering, and chaotic centerpiece on “Laugh Track”—“Space Invader,” where Berninger, while both ruminating from within his writer’s block, walks us back even further, and with serious earnestness, wonders what would have happened if he and Besser had never crossed paths at all, or if he had not, in one of the most resonant lines of 2023, written her a letter and put it in the sleeve of a record.

An argument can be made, and has often been made, that a lot of The Nationals canonical works, especially in the last five or six years, has suffered from multi-instrumentalist Aaron Dessner’s production and arranging, and that a lot of their music, in terms of tone and dynamism, finds itself in a holding pattern of a specific sound. It does work for me, or is something that I do genuinely like, but I understand that it is not for everyone. Admittedly, from the way these songs are orchestrated alone, the reliance on drum programming rather than the powerhouse percussion of Bryan Devandorf is a source of frustration, though his work behind the kit is more prevalent on Laugh Track, thankfully. And when the band hits a stride, and all of the elements that they are, at current, working with, come together well, things really do work, and sound incredibly robust and sweeping.

Across both albums, though, it does come back to Berninger’s writing—and the way he has unflinchingly depicted the decline of his mental health, and the ultimate toll that it took on those around him. Perhaps most graphic, or truthful, in the prologue to First Two Pages, “Once Upon A Poolside,” but it is present elsewhere even in passing phrase turns within “This Isn’t Helping,” “Your Mind Is Not Your Friend,” or “Tropic Morning News” (even with as jaunty as the song with its relentless rhythm and searing guitar work.) And it’s also present in the songs that are more about interpersonal connections, or his own relationships, like the cinematic and deprecating “The Alcott,” which boasts an appearance from Taylor Swift, or within “Hornets” and “Coat on A Hook,” tucked within the second half of Laugh Track.

First Two Pages of Frankenstein and Laugh Track are not the sound of a band on the brink, but a band that was close to the edge, found their way back, and in doing so, managed to reinvest in themselves. There are flaws, certainly, across both, but these companion albums are quite vibrant texturally, thoughtful lyrically, and even when they operate from a place of sorrow, there is that is still so invigorating and exciting, for me, about The National.

Chappell Roan - The Rise and Fall of A Midwest Princess

And I think the thing that is, perhaps, my favorite component to The Rise and Fall of A Midwest Princess, the long-gestating debut full-length from Kayleigh Amstutz, who records and performs under the name Chappell Roan, is, outside of often being an album that is more fun than legally allowable, it is just simply audacious.

Audacious, yes, and surprisingly, and admirably, brazen, which is what contributes to making it as fun and as razor-sharp of a listen as it is.

From the floor of a very underwhelming and cramped Airbnb in Duluth, in the dead of winter, near the beginning of 2022, where I sat attempting to calm an anxious and playful dog we had adopted five months prior, I was both trying to edit an episode of the interview podcast I host and produce, and browsing Instagram while the conversation played through my headphones. And it was on Instagram where I saw the cover art for Amstutz’s single, the writhing, sapphic “Naked in Manhattan,” shared in a post from producer Dan Nigro, with whom I had become familiar with through is work collaborating with Olivia Rodrigo on her blistering debut, Sour.

A similar formula to the one Nigro and Rodrigo used in their work on both Sour and, later on, Guts, is what, I think, makes Rise and Fall such a dynamic, well-produced, and intelligent pop record—Nigro produced the record entirely, and is credited as co-writing the album’s 14 tracks alongside Amstutz, with their collaboration resulting in songs that are infectious and dazzling, carried by the impressive vocal performances from Amstutz, and the youthful, playful charisma she exudes at literally every turn.

Opening with a sweeping and saccharine string arrangement, she laments about the disappointments of modern romance. “He disappeared from the second that you said, ‘Let’s get coffee—let’s meet up,’” she observes. “I’m so sick of online love.” Amstutz, who came to understand her queer orientation during the writing process for the album, then bellows, moments before the scream-along chorus, “I don’t understand—why can’t any man…”

The self-aware sense of humor, and camp explodes, then, as, before the song kicks into overdrive, she demands that Nigro play a song with “a fucking beat”—something she screams with increasing intensity each time the duo arrives at the chorus, which is unabashed in its chaotic fun, as Amstutz sings, hypnotically, “Hit it like rom-pom-pom-pom. Get it hot like Papa John. Make a bitch go on and on—it’s a femininonmenon.”

The commitment to audacity and camp continues in the sultry, scuzzy, pleading “Red Wine Supernova,” which, like its predecessor, was among the staggering nine of the album’s 14 tracks to be issued as a single ahead of Rise and Fall’s September release. And “Red Wine,” like a few other moments throughout, is where Amstutz writes with a smirking, frank, and lusty nature, which, much like the enormity of the album itself in sound and scope, is wildly refreshing.

“I like what you like,” she sings playfully in “Red Wine Supernova”’s second verse. “Long hair, no bra—that’s my type. You just told me want me to fuck you…Baby, I will, ‘cause I really want to.”

Slightly less audacious, but no less fun, and no less campy, are songs like the aforementioned “Naked in Manhattan”—which, as it slithers along, ends up treading the line between playful and sensual, with Amstutz using the opportunity to again explore her sexual orientation. “Touch me, baby, put your lips on mine,” she commands. “Could go to hell, but we’ll probably be fine. I know you want it, baby, you can have it. Oh, I’ve never done it—let’s make it cinematic like that one sex scene that’s in Mulholland Drive.” And this leads up to the big, lusty, swirling chorus, where, when not repeating the titular phrase, continues demanding, “Touch me, baby.”

That unbridled lust, and rollicking, winking kind of humor and camp is what makes the buoyant “Hot to Go” as compelling and gleeful as it is. Complete with a brief dance that Amstutz instructs you how to do during the chorus (another enormous shout-along opportunity), over an absolutely unrelenting beat and 80s-inspired synthesizer tones, she makes her intentions known. “Baby don’t you like this beat?,” she asks. ‘’I made it so you’d sleep with me. It’s like a hundred ninety-nine degrees when you’re doing it with me.”

And perhaps that, outside of how enormous this album is, and how brazen and audacious Amstutz and Nigro are in their approach, what is most impressive, or at least the thing that I continue to focus on when I have returned to The Rise and Fall of A Midwest Princess, which, since its release, is an album that I do return to quite regularly, is just how dynamic it is in tone. Because for as often as the album is here for a good time, and encourages us along with it to have a good time, or have fun, it does both a mid-tempo jam and a smoldering ballad extraordinarily well.

Originally issued as a single roughly a year before the album’s arrival, and placed early on in its sequencing, “Casual” was one of the first indicators of just how diverse of a performer Amstutz was—slow and hazy in its rhythm, the production values themselves are intentionally fuzzy and distant sounding, with noisy, buzzy synthesizers and muffled, but clattering percussion all rippling around as the lyrics detail the difficulties that come from when one person in a romantic relationship is keeping the other at an arm’s length. Self-effacing and biting in its writing, it is within the chorus to the song where I can remember, the first time hearing “Casual,” that I realized just how impressively bold Amstutz was as a writer: “We’re knee deep in the passenger seat, and you’re eating me out,” she exclaims with a mournful tinge to her voice before asking, “Is it casual now?”

Far less lusty, or sensual, is the scathing vitriol of the dazzling “My Kink is Karma,” where, in the wake of a messy breakup, Amstutz, over a heavy-sounding synthesizer and chintzy-sounding drum machine pattern, works herself up (and eventually, the song’s arranging, too) into a frenzy by thinking of a series of horrible things happening to her former partner. “It’s comical, bridges you burn,” she observes in the second, slow-burning verse. “Karma’s real—hope it’s your turn.”

“It’s hot when you have a meltdown in front of your house and you’re getting kicked out,” she sings with a strange blend of anger and sensuality in her voice, before, a few lines later, leads us into the shimmering, ascendant, and gigantic chorus. “People say I’m jealous, but my kink is watching you ruining your life, you losing your mind…you crashing your car, you breaking your heart, you thinking I care—people say I’m jealous, but my kink is karma.”

And with the smoldering, sparse ballads, like heartbreaking “Coffee,” or the bittersweet longing of “Kaleidoscope,” Nigro and Amstutz know, in sequencing the album’s 14 tracks, where the pacing, or momentum of the album could benefit from slowing down slightly, before, in each instance, they work toward building it right back up. There are little if any reprieve from the energy this album has, but these are the moments where that enthusiasm does take a short break, and in doing so, allow a tender, melancholic side of Amstutz as a songwriter to show.

In a sense, the two tracks are mirror images of one another—“Coffee” is a pensive look at life, and love, after a breakup when one person has not, as of yet, been able to let go of the feelings they have. Over delicate, stirring piano, Amstutz finds that she is unable to meet a former partner literally anywhere (an Italian restaurant, or a jazz bar, or the park) because there are too many memories, or implications, coming from each location, except for grabbing a coffee. “I’ll meet you for coffee ‘cause if we have wine, you’ll say that you want me,” she admits. “I know that’s a lie. If I didn’t love you, it would be fine—meet you for coffee, only for coffee. Nowhere else is safe. Every place leads back to your place.”

And if “Coffee” is about the aftermath of when a relationship is over, but a confusing kind of love remains, “Kaleidoscope” is when there is a confusing kind of love forming in the wake of something unexpected. “I guess we could pretend we didn’t cross a line,” she sings early in the song. “But ever since that day, everything has changed. The way I write your name—a cursive letter A.”

Less stirring, and much more dramatic in its arranging on piano, matching the heartfelt vocal performance from Amstutz, who sells both the love and the trepidation over that love within the chorus—“Whatever you decide, I will understand. And it will all be fine, and just go back to being friends,” she tries to concede. “Love is a kaleidoscope. How it works, I’ll never know. And even all the change—it’s somehow all the same…even upside down, it’s beautiful somehow.”

And there is, of course, a kind of escapism that comes with pop music, which I think is part of the allure of an album like The Rise and Fall of A Midwest Princess, and Chappell Roan as a persona, or an extension of Amstutz as an individual growing into herself and her identity still.

The album, as a whole, is so youthful, accessible, and inviting that it never makes you, as a listener, of any demographic, feel unwelcome at its table, and the exuberance it propels itself forward is not a cure for the human condition, but it is something that, for roughly an hour, allows us to forget.

It is an enormous, bold, and stunning debut from an enormous, bold, and stunning new artist.

Olivia Rodrigo - Guts

Pop music, and a lasting, impactful sense of catharsis, are things that, at first, might not be synonymous with one another. Because, pop music, anecdotally, is about an escape. It’s about a vibe. It wants to have fun, and it wants you, the listener, to have fun along with it—it, often, can be less concerned with lyricism, or is not interested in opening itself up to analysis.

But there are times when pop music is, or at least can be, genuinely interested in catharsis. And when it comes in a moment—enormous, and perhaps much more powerful than you were anticipating, it does really stay with you, for months, or in some cases, years, after you first heard it.

At the beginning of 2021, Olivia Rodrigo did not have to go as hard as she did with her instantly ubiquitous debut single, “Driver’s License,” but she did it anyway—a song that was so expertly crafted by Rodrigo, and her collaborator, producer Dan Nigro, that its command of tension and release is as impressive today as it was when I first heard it. Because there is truly something incredible about howling along with her—when the verses swell up to the gigantic peak of “You didn’t mean what you wrote in that song about me,” or in the now iconic bridge which houses the line, which she belts, and rightfully so, “I still fucking love you.”

And there was, truly, no way that Rodrigo’s second full-length, Guts, would disappoint, or would somehow fall short of the preternatural potential demonstrated on Sour, though it might behoove us, as listeners, and as the audience, not to put undue pressure where it is certainly unnecessary. But Rodrigo and Nigro took that pressure and managed to work with it, and in the end, ultimately use it as a reference point, to create a huge, bombastic, bright, and thoughtful pop record that, like its predecessor, contains impressive moments of absolute catharsis, and doubles down on the bratty, brash, pop-punk sound that, outside of being bombastic, bright, and often thoughtful, makes for a collection of songs that is, as a whole, fun as hell to listen to.

Across the album’s 12 tracks, Rodrigo walks the line between slow burning, pensive ballads, like the speculative “The Grudge,” and the heart wrenching depiction of difficult love, “Logical,” and if not slow burning, and pensive or at least much more introspective, and surprisingly (and refreshingly) somber moments, like the reflective, melancholic, and restrained “Making The Bed,” and the sneering, angsty ferocity from shout alongs like “Ballad of A Homeschooled Girl,” “Get Him Back,” and the snarling, sardonic opening track, “All American Bitch.”

There is only one real moment when the album falters, early on, and really, Guts is a collection that continues to surprise the further you get into it—with Rodrigo tapping into a writhing,1980s New Wave sound on the unrelentingly energetic “Love is Embarrassing,” which, too, has its share of opportunities for a shout along. Certainly within the chorus (“Now it don’t mean a thing. God, love’s fucking embarrassing”) as well as within the dissonant, borderline unhinged delivery of the closing lines, “I give up, give up—I give up everything! I’m planning out my wedding with some guy I’m never marrying,” Rodrigo yelps while the song’s dense, shimmering arrangement nervously jitters around her. “I’m giving up, but I keep coming back for more.”

And just a few songs later, near the conclusion of the album, there is the equally as surprising and as genuinely interesting turn into something startlingly dreamy and indie rock adjacent in its aesthetic, with the self-deprecating, hazy “Pretty Isn’t Pretty.”

Pop music, and a lasting, impactful sense of catharsis, are things that at first might not be synonymous with one another, but there are times when pop music is, or at least can be, genuinely interested in providing that kind of moment of catharsis—enormous, and much more powerful than you were anticipating.

Something that really does stay with you for months, or in some cases, years after you first heard it.

Rodrigo did that in 2021 with “Driver’s License,” and she did it again with both singles released in advance off of Guts—the seething, regretful, and explosive “Vampire,” and the playful, sensually charged, and ostentatious “Bad Idea Right?” The former, at first, showing signs that it might, in some regards be similar to “Driver’s License” in structure, but she and Nigro never allow the song to truly fall into a familiar pattern, as they keep pushing the song forward toward greater momentum until bursts at the seams.

And it, like “Driver’s License,” and like so many other places across Guts, includes the key moment to scream along with—this time, with a startling about of vitriol in its lyrics, as Rodrigo, at the end of each chorus, lands on the following phrases: “Bloodsucker. Fame fucker. Bleeding me dry like a goddamn vampire.”

“Bad Idea Right,” placed second within the album’s running, is its most relentless in exuberance, assembled that so after Rodrigo slyly talk/sings her way through the verses, she pulls us, as the listener, through a series of escalating and infectious instances—the first of which is the charm of her chanting “I should probably, probably not,” followed by the urgent assurance, through gritted teeth, “Seeing you tonight is a bad idea, right?,” which, after repeating with a growing sense of desperation, she lands on the whispered punchline of the song: “Fuck it, it’s fine.”

Neither of these parts to “Bad Idea Right” is the actual chorus to the song—over noisy guitars and bashed-out drums, Rodrigo, with razor-sharp precision, lets the words come spilling out of her as they land exactly where they are supposed to within the cacophony below: “Yes I know that he’s my ex but can’t two people reconnect? I only see him as a friend—the biggest lie I ever said.”

The thing that I kept coming back to when I was writing about Sour, in the spring of 2021, was the line Rodrigo utters in “Good 4 U,” where she says, “Maybe I’m too emotional,” because the more I thought about it—what I realized was, first, aren’t we all; and second, is there something inherently wrong with that. Two years removed from her breakthrough, Guts is a huge and thoughtful statement—fun and funny as it is arresting in how insightful it is, that follows Rodrigo as she continues to grow into herself as a person and an artist, and shows time and time again that there is still nothing wrong with being too emotional.

Jonah Yano - Portrait of A Dog

If there’s one thing I know, it’s you—there’s something about how you were holding onto grief…

Something that I started doing around seven years ago, and have not really been able to stop myself from doing it, is, in my over-analysis of pop music, identifying when a specific lyric, or perhaps the entire song itself, is incredibly toxic—and often, when it is written, and sung, by a man, when the lyricism finds itself within what at least I feel is toxic masculinity.

It started innocuously enough in noticing examples within beloved songs from the past—i.e., “The Distance” by Cake or “Barely Breathing” by Duncan Sheik. And this is not to say that men cannot, if they feel so inclined, write about heartbreak, but it almost always comes of sounding a certain way to my ears when I really sit down and contemplate the writing, and what they were attempting to convey.

And it took me nearly the entire calendar year to realize the small ripples of that kind of wounded toxicity in the dizzying, gorgeous second track on Portrait of A Dog, from Jonah Yano—and it took me from when the album was released, at the end of January, until now, for a few reasons. The song in question, “Always,” is, simply putting it, jazzy and rollicking fun. It sounds big without being boastful, taking huge musical swings and always connecting, but doing so in a way where there is a little bit of restraint shown even when the musical’s Yano is working with—the critically acclaimed contemporary jazz outfit BADBADNOTGOOD (stylized just like that), start to show off just a little bit, rather than showing out, with just how tight of a group they are, and how tight they sound on this record as Yano’s band.

Yano’s voice, too, also partially hid the lyrics I am now able to identify in their borderline toxicity, because he does sound so relaxed, and light. And in that lightness, and relaxedness, there is a soulful quality to his vocal delivery that comes through, but it is an uncharacteristically quiet kind of soulfulness that is never at risk of overpowering the instrumentation, so there are times when he almost takes a backseat within his own song. It’s not a good or a bad thing, just something that I continued to realize the longer I spent with Portrait.

One of the things that first drew me to explore Portrait of A Dog, upon its release, was that it was a concept album—one structured around the ideas of impending loss and grief, and memory, as well as heartbreak. And it is, as you may anticipate, the heartbreak, which leads to lyrics like the lines in the aforementioned “Always,” that I call into question.

“The way she left you feeling is the opposite of care,” he sings, his voice so soothing and woven so well into the fabric of the instrumentation that keeps spiraling around him—and he does repeat the expression, “The opposite of care,” four additional times, and it was, finally, in sitting down to listen to this album with the intention of analysis for this year-end list, that I understood what was happening.

“The way you left me feeling is the opposite of care,” he continues at the end of the second verse, building up toward the grand, sweeping chorus. “It’s the opposite of care—and was the feeling ever there?”

There is beauty, though, from beginning to end, on Portrait of A Dog—and album that is, at its core, about a breakup, certainly, but its conceit also lies within Yano’s attempts to remain connected to his grandparents, both of whom were forget things. Like his name, apparently, per the review of the record featured on Pitchfork, which is how I was first introduced to it.

In being open and honest, outside of name recognition, I know very little about BADBADNOTGOOD, and I know even less about Yano—save for the other album he has released under his own name, issued in 2020 (which I have not had a chance to sit down with), and a single that he recently put out, so my fondness of Portrait of A Dog, at year’s end, is indicative of the moment it creates and sustains, more than anything else.

It is a hypnotic, warm, and inviting album in sound—a delicate, often fragile kind of gorgeousness that stems from both the range and tone of Yano’s voice, as well as the fun, relaxed, and often impressive music, which finds a space between jazz, or jazz adjacency, and indie folk, perhaps. It doesn't defy classification exactly but it presents a challenge to accurately describe.

Musically, Portrait of A Dog is bold without being completely grandiose, and even though it does, rather quickly settle into a kind of comfort zone of an aesthetic, it does, as a whole, leave a little room to move around in how it explores a restrained, mournful kind of soulful or R&B sound with the groove Yano and BBBNG find themselves in on the titular track, or the “soft rock” tenderness from the twinkling piano keys, low sweeping of the cello, and the steady, crisps sounding percussion of “Call The Number.”

Within how the album is structured, it does not exactly play its hand within its first half, because there are moments to behold, and moments of genuine interest, in the second half, but perhaps the more accessible and welcoming material does arrive at the top—and yes, even with its questionable display of emotion in its lyricism, “Always” is an absolute stunner and high point on the record, as is the insular, “Haven’t Haven’t,” which is less rollicking, and much more melancholic with its focus on the acoustic guitar, and additional wind instruments accompanying along until the percussion comes tumbling in.

And because Yano’s delivery of his lyrics is so relaxing in a way where his voice is not entirely the main focus, but rather just an additional element to a larger whole, the kind of imagery that he does end up writing about can be missed unless you know to look for it, or have been listening so intently. The vivid but fragmented and vague imagery he conjures in “Haven’t Haven’t” is as impressive as it is stirring—“I’m very close by with a friend. I know it’s been a while, but would you like to talk to me,” he begins, before easing into the short chorus. “And you were very closet o me at home. And seal an envelope for rose at home.”

Or, the surprising way he opens the titular track, his voice unaccompanied until the final line before a delicate, acoustic, warm groove comes coasting in—and the unaccompanied nature allowing the poignancy of the lyrics to sink. “If there’s one thing I know, it’s you,” he begins. “There’s something about how you were holding onto grief. The tide doesn’t change the see, but it sure sinks its teeth in me if I’m holding onto you.”

The thing about Portrait of A Dog is that the thematic elements of grief and heartbreak do not cast all that long, or dark, of shadows throughout it, and certainly, the album’s commitment to a specific sound that is not really all that dark at all gives this collection a surprising, and welcomed, lightness—not as a means of distraction from the gravity of the emotions that comes from the end of a relationship and the reluctant acceptance of mortality, but more of a way to off-set it. But as the album arrives at its penultimate track, “Song About The Family House,” it is impossible to forget the conceit that Yano has spent the entirety of this record sustaining.

Over just an acoustic guitar, he reflects, “How do I keep the living room intact? Exactly as it was. If I have to commit it and rebuild it in my memory. There’s nothing cruel as the route of the truth from your mouth that I hold close to sentiment when a moment is undone.”

“But my home is a house,” he continues. “And not any city I’ve talked about. So bury me on Jefferson Street. Replace me with concrete and all of the stories I’ll keep between family—it’s just me.”

Portrait of A Dog is a brilliant and thoughtful reflection on things that are ultimately unavoidable, and in that inability to avoid both grief, and heartbreak, and loss, Jonah Yano navigates both with admirable grace and beauty.