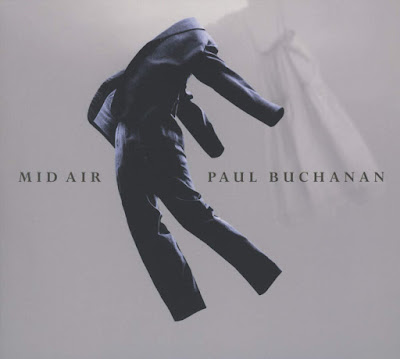

Are You Trying to Tell Me What I Already Know? - On Loneliness and The Tenth Anniversary of Paul Buchanan's Mid Air

And it is not an idea that I have spent a lot of time, in the past, thinking about, but it is something that has been on my mind as of late—and what I am uncertain of is why it had not occurred to me, before now, to use this idea as a point of access, or as the conceit, when thinking about, and beginning to write about, the tenth anniversary of Mid Air, the only solo album from the seemingly reclusive Paul Buchanan, the former lead singer and principal lyricist to the beloved cult outfit The Blue Nile.

And I used the word itself twice when I wrote about The Blue Nile’s seminal sophomore album, Hats, when it was reissued at the end of 2019—both in conjunction with the album’s thirtieth anniversary as well as part of the campaign to reissue all four of The Blue Nile’s studio albums on both vinyl and expanded double CD editions. And it is a word that Buchanan himself uses in a question that he poses in a song, and is the title of that song as well, however it was not included in the final cut of Mid Air, only later included on a bonus disc of b-sides, alternate mixes, and instrumental versions, appearing around five months after the album was initially released in the spring of 2012.

And it is that question that begins the first side of the second LP in the recently released tenth-anniversary reissue of Mid Air. And it is not a question that is, like, the key to a greater understanding of the album—not exactly, but it is a word, and a word within a question, that perhaps, after ruminating on it within this context, allotted me a much greater appreciation to what the album winds up inherently being a meditation on.

The word is “lonely.”

And the question that Buchanan asks, in the opening line of a song placed at the start of the album’s third side, is “Have you ever been lonely?”

And it makes sense that this would be the question, and that “lonely” or “loneliness” would be the word, because there is an icy, at times seemingly dark sense of pensive loneliness that is found in nearly every song, both musically and lyrically, on The Blue Nile’s Hats—and well over two decades later, recorded when Buchanan was in his mid-50s, Mid Air more or less lacks the preoccupation with mortality one may think would be found on a late-career album such as this, but rather, it is written from a place of terrible, though often beautiful, wistful longing, often for something—or someone, connected to a lifetime that has long since passed.

Fragments continually slipping through fingers.

A bittersweet loneliness that always lingers.

*

Perhaps you are like me—you are a person who often purchases books, but for whatever reason, might never get around to reading some of them, despite whatever good intentions you might have.

They sit, either on a shelf in the living room, filed alphabetically, or they form a pile on the bottom shelf of your nightstand, sadly collecting dust as the days turn into weeks, then the weeks into months, and then the months into years, and the books are shuffled around every once in a while, the dust wiped off, and then re-stacked with the belief that, someday, they will be read.

This would have been at least two years ago when I felt compelled to order a copy of Nileism—The Strange Course of The Blue Nile, Allan Brown’s biography about the beloved, partially mysterious Scottish band that Paul Buchanan formed in 1981 with Robert Bell and Paul Joseph Moore.

And I am uncertain if I ever, at any point during 2020, or even into 2021, made an attempt to begin Nileism, and found that I was simply just not in the mood to read a somewhat sprawling and lengthy music biography, or, if it was a book that I just felt compelled to order after I had immersed myself in the band’s catalog upon its reissuing, and was content with placing the book on the bottom shelf of my nightstand, occasionally wiping away the dust that collected, and shuffling it around within the stack of my ever-present “to read” pile.

Originally published in 2010, Nileism was reprinted nine years later, however it was not updated or revised. Not that there was, like, a demand for the book to be revised upon its reprinting, though updating it could have provided readers with information about The Blue Nile’s reissue campaign—launching near the end of 2019 with the re-release of A Walk Across The Rooftops, Hats, and Peace at Last, with the band’s final studio album, High, arriving in the summer of 2020.

A revision could also have provided some information about Buchanan’s solo foray with Mid Air—released two years after the book’s original publication, the beginning stages of the album are mentioned, almost off-handedly, in a few sentences near the book’s conclusion. The album, then untitled, is referred to as a “seventeen-song suite for piano and vocal.”

A “suite” for piano and vocal is a generalization of sorts, yes, but it is probably the easiest way to describe Mid Air at first—in this context, a suite is defined as a set of musical compositions to be played in succession. And that’s the thing about Mid Air—it isn’t impossible to extract songs out of its run to be listened to on their own, but it is intended to be listened to as a whole, and the songs themselves work better when listening uninterrupted from beginning to end. Buchanan has created an extremely insular world, especially in how similar so many of these songs sound—and leaving the world before he is ready to let you go is, again, not impossible to do. However, the album's emotional resonance is diminished if you choose to exit before Mid Air reaches its intended conclusion.

*

What I find is that I am thinking about the differences, whatever those might end up being, between feeling “lonely,” or a “loneliness,” and feeling “alone.”

Because there is a place, of course, where those feelings begin to not converge so much as overlap, but they are feelings that begin in different, but not opposing, places before that overlapping occur.

I am thinking of a quote from Toni Morrison’s Sula—“Yes, but my lonely is mine.”

*

One of the things that struck me immediately about The Blue Nile—Hats in particular which is, of their four studio albums, considered to be their finest and most cohesive artistic statement, is the extremely evocative imagery Buchanan often used in his songwriting.

And I am finding that it is challenging—perhaps more than I was anticipating- to write about the scope and focus of Buchanan’s lyricism with any kind of clarity or articulation.

If we compare Hats and Mid Air, both of them have an insular nature, but there is a different kind of insularity in each—or rather, a different kind of world that has been built for each. The portraits painted on Hats conjure late nights on cold and rainy city streets—perhaps the reflection of a neon sign glistening off a pool of rainwater forming near the curb, or dancing across a car that slowly drives by, but more importantly than that kind of a feeling, there is a desperate longing and sense for connection, or in various moments throughout, a fading flicker of hope.

The Blue Nile’s debut, released in 1984, was titled A Walk Across The Rooftops, and it is the only album, out of their four studio recordings, that features all three members in the photograph found on the cover—washed out and black and white, they stare at a dilapidated building you’d find in a major city. Even with that literal imagery, and a title that calls to mind a more urban setting, it is within Hats where you find yourself deep in the heart of the city, losing yourself in the night, trying to assure someone of a potential, or a promise, that you have no intent on keeping, and you are just desperate enough to convince them otherwise.

Hats can be insular, yes, because there is a similar tone that courses through the album, but the songs are also structured in a way where they are able to stand on their own, and be removed from the context of the album as a whole.

I hesitate to say the scope and focus of Mid Air are larger, because that is inaccurate—as an album, there is little, if anything, large about it at all. It’s an intimate recording—perhaps among one of the most fragile and hushed records I have come across in recent years. But even within how physically close to the music, you are as you listen to Mid Air, and even within how interconnected its “suite” of songs are, it is an album that looks at the past thoughtfully, and does so from a much further away kind of emotional geography than the feeling of the “city at night” from Hats.

Mid Air finds itself somewhere between the pastoral and the provincial, then slowly and deliberately closes in on specific moments and slightly fading memories.

*

Around the beginning of the year, I read The Sea, a novel by the Irish author John Banville. In it, the protagonist, ruminating on the recent death of his wife, returns to the seaside town where he spent the summers of his youth, and throughout the narrative, often without coming up for air, interweaves and attempts to unpack both the grief over his wife’s passing, and a childhood trauma he seemingly never really came to terms with at the time it occurred.

Often dense and complicated in the way its story develops and unfolds, I thought the most compelling part of The Sea was the way it played with the concepts of time and memory—doing it with a spectral beauty, extraordinarily vivid in the detailing and language Banville used.

And there is a haunting quality within much of the songwriting on Mid Air, with Buchanan also playing with the notions of time and memory, and providing excruciating detail at times on seemingly the most insignificant things, but using those to craft much larger, vibrant, and gorgeous moments.

Because Mid Air is referred to as a “suite,” I find that I am having difficulties coming up with another way to describe the material found within this album—they are songs, yes, of course, they are, in the sense that there is music being played underneath and a voice carrying notes and following a melody. Still, they are not “songs” in a traditional pop song sense of the word, or the concept, because they are often so sparse and intimate, with many of them structured in a way that does not follow the typical “verse, chorus, verse” organization. They meander, lyrically at least—often like someone with a story about the past that they desperately want to share. They, at times, get hung up on one specific phrase or detail, not entirely turning it into some kind of incantation, but creating a surprisingly hypnotic, resonant effect.

The longest song on Mid Air—at least on the album’s original CD release, is its closing track, “After Dark”—pensive, deliberate in its pacing, and roughly four minutes in length; its shortest is “Newsroom,” which is less than two minutes, twinkles, rising and falling with a sense of melancholic whimsy, thanks to the very dated sounding synthesizer Buchanan uses in the song’s arranging.

Even with the relatively concise running times, and with the kind of literate, poetic, storyteller nature of Buchanan’s writing on Mid Air, the tunes here never feel rushed or unfinished, per se—they, at times, feel intentionally fragmented—focused so intently on specific moments or details. When that moment has come and gone, or the exploration of the detail has been exhausted enough, Buchanan opts not to overstay his welcome.

The reissue of Mid Air pairs the original album—fourteen tracks total, on one LP, with the supplemental material that was available on the album’s bonus disc in 2012—appearing for the first time on vinyl within this set. And across those fourteen tracks, Buchanan, as an arranger, rarely strays from a specific sound and tone on the piano—and with Mid Air being referred to as a “suite,” it makes perfect sense that many of the songs within this cycle would sound similar. Still, there are moments when, because of how the album is paced (in all of its quiet and reserve, it does move along quite slowly), it can become a little frustrating when there is little, if any, dynamism from song to song.

Mid Air is perhaps structured so that it is front-loaded with its best, or at least most emotionally gripping and compelling material within its first side—even within the little deviation from how the songs from this half of the album sound, Buchanan is quite honestly at his finest in terms of creating, and then sustaining, a mood—gorgeous, delicate, and absolutely heartbreaking.

The album opens with its titular track—a piece that isn’t exactly a thesis statement for the things to come as the rest of Mid Air unfolds, but it does really set a tone as Buchanan moves back and forth between chords that have the slightest dissonance to them, before allowing himself a little musical resolve. There is a sense of tension, or heaviness as it opens, that he returns to throughout “Mid Air”’s two-and-a-half-minute running time, but when he allows himself to wander away from that heaviness, it grows just a little lighter—somewhere between the melancholic and the whimsical.

I hesitate to refer to those as “extremes,” because in an album this hushed and fragile, there is really nothing extreme about it, but Buchanan, as the album continues into “Half The World,” and “Cars Are In The Garden,” finds himself working within those highs and lows, musically speaking, in terms of tension, and a palpable sadness that he pushes and pulls into something bittersweet.

Something I think about, when I think about The Blue Nile, is how their music—the sound of it, specifically, has aged over time, because there are moments on Hats that are able to transcend any kind of late 1980s synth-heavy pop trappings, and it still sounds extremely relevant and borderline timeless, thirty years later; there are also moments where that is not exactly the case, or the era which the music was made shows its hand a little more.

Part of the mystique or like the allure around The Blue Nile is the years of relative silence and reclusiveness in between their studio albums—five years in between their debut and its follow-up, then a staggering eight years between Hats and the maligned Peace at Last, and then another eight years until their final album, High, released in 2004. Never a band to fall into the whim of current trends in contemporary popular music—strangely making certain moments of High sound like they were recorded upwards of 15 years prior in terms of their production and the overall sound and style.

And I bring this up because even though Mid Air is billed as a suite for “piano and vocal,” there is other instrumentation, albeit subtle, used throughout the album, but there are moments when it gives Mid Air a strangely dated sound—making it appear as if it was recorded years before 2012—the sweeping “Newsroom” is probably the best example of this kind to antiquated aesthetic, at least within the album’s first half with its layers of gauzy, twinkling synthesizers that sound like they were exhumed from another era of pop music.

And yes, the subtle inclusion of additional instrumentations in these songs adds just the right amount of depth to them when it’s needed—the quiet washes of synths in the background, string arrangements, or a mournful sounding horn, but because these layers are so subtle, and because there are moments on Mid Air that sound much more dated than it should for a record made a decade ago, it can be difficult to figure out if these elements are actual strings being played by a small ensemble, or a genuine horn being blown into, or if they are artificial—coming from yet another keyboard in Buchanan’s array.

And there are inconsistencies, or at the very least, difficulties within the production with these additional layers of instrumentation, because it seems there are times where he favors real string accompaniment in some songs, while including the synthesizer or MIDI-created equivalent in others—the latter of which, along with the somewhat antiquated sound the album can have at times, also makes it sound a little chintzy, ultimately distracting from the emotional resonance of Buchanan’s lyricism.

And like the music itself, which can be difficult to analyze with any kind of articulate clarity, Buchanan’s lyrics are similarly difficult to provide any type of in-depth analysis of simply because of the way these pieces unfold—not like sketches exactly, but like fragments, where there are specific things throughout that are a little more resonant than others wind up being. Mid Air, lyrically, is again like the book The Sea—a first-person, character-driven narrative where there are certain lines, or passages, that is exponentially more poignant or memorable than others—the kind of phrase turns that linger well after you’ve made it to the final page. In all of his wistful melancholy, Buchanan’s writing is similar in the way there are very specific lines, or moments, that haunts like a specter of loneliness well after the final notes have dissolved into the ether.

Mid Air begins with its titular track, and with the depiction of small, yet vivid details—“The buttons on your collar. The color of your hair,” Buchanan sings quietly and delicately. “I think I see you everywhere.”

“Mid Air,” as a song, like a number of the songs on the album, blurs the line between these lived-in moments, or somber fragments, with his attention to specific, often seemingly trivial or overlooked details. “And only time can make you the wind that blows the leaves away,” Buchanan observes shortly before the conclusion of the track. “For everything that life was worth—the fallen snow, the virgin birth. Yeah, I can see her standing in mid-air.”

It was surprising to me, when sitting down with Mid Air to listen analytically, how many biblical or at least religious allusions and references there were, as they are something his writing with The Blue Nile did not include. On the delicate, and rather desperate sounding “Half The World,” Buchanan sings, “The astronaut in God’s blue sky, dreaming of a summer day and waving his last goodbye,” then, getting the phrases that linger well after the song is over: “There were reasons, but we forgot them. Nothing stands here, our way. For the starlight in my suitcase and for the good days—don’t leave.”

The literate nature to a lot of Buchanan’s songwriting on Mid Air can also turn into something much more poetic and slightly more ambiguous in its use of imagery—still vivid, of course, but becoming more of a challenge to try and completely understand, like “Wedding Party,” which arrives near the record’s the halfway point, where against a gentle piano accompaniment, Buchanan just lets his words very deliberately, but freely, tumble out into the music.

“It’s a good day for a landslide,” he began with his voice remaining quiet and fragile. “There are tears in the car park outside…We were lost under glittering skies. Are you trying to tell me what I already know?,” he continues. “Let Me go.”

The most poetic, or at least most poignant and memorable, line comes near the end—“I was drunk when I danced with the bride. Let it go.”

“Movie Magazine,” sequenced within the album’s latter half, is similar in how Buchanan steers his writing in a vague, poetic direction. It is, like a few of the songs near the top of the record, another place where he makes a religious allusion—“Is Jesus on the telephone? Or is he sleeping?,” he begins as the song opens, before, a few lines later, making seemingly ordinary observations appear much more poignant and weighted than one might give them credit for—“The coffee is cold and out of reach,” he sings. “You are mistaken.”

I am somewhat remiss to say that Mid Air loses some of its energy, or enthusiasm, as it gets into its second half simply because an album that is this reserved and full of a simmering, bittersweet tension is anything but energetic or enthusiastic, but there does reach a point in the second side where the songs are slightly less captivating on an emotional level, or less impactful than they were on the first half.

After an unfortunately ill-fated instrumental composition—“Fin De Siecle,” Mid Air’s penultimate track, which is the place where the lines blur the most in my inability to properly tell which instruments are coming from a synthesizer, and which instruments are actually present and being performed (it also sounds like the kind of thing you would hear edited in underneath somebody’s wedding video), the album ends with “After Dark,” and like the way Mid Air begins in a near whisper, slowly circling a place of wistful reserve, the album, fittingly ends that way as well.

“After Dark” is the album’s longest song, and there is a slightly more relaxed feeling to it, or at least one where Buchanan is singing from a place of somewhat less restraint, though still extraordinarily melancholic, and perhaps the most regretful or remorseful in terms of its lyricism. “Life goes by, and you learn how to watch your bridges burn,” Buchanan muses in the song’s first few lines, then later, one final bit of poetic, vivid, ambiguity—“Evening falls on me now. A carousel on empty ground.”

Like a majority of the songs on Mid Air, there is no clear chorus on “After Dark,” but lines that find themselves being repeated, or returned to. And here, like Buchanan did years before this in the assurances he made, but was unable to keep, on Hats, there is a somber desperation to the way he speaks of love, or tries to convince someone of love, while the album is coming to its end. “Didn’t I tell you everything you wanted?,” he asks. “That I loved you, and I love you, after dark.”

*

Paul Buchanan was in his 50s when Mid Air was written and recorded—and into his 30s during his time with The Blue Nile. And I bring this up mainly because there is something—not strange, but there is something about his usage of the expression “motor car” that I find fascinating, especially now, in 2022, ten years after the album was initially released. There’s something extremely antiquated about it—which is why the album sometimes seems to be coming from somewhere between the provincial and the pastoral. Just in that description alone, something brings to mind an entirely different era.

I hadn’t considered that until now, listening more analytically than I have in the last two years since I was introduced to the record, and what I also had not considered until now was if any of these songs at all could lend themselves to being developed further with additional instrumentation and become Blue Nile songs. And out of them all, “Buy A Motor Car” is the one.

Mid Air is not an album that is designed to have any kind of songs with the potential to be a single, but I get the impression that “Buy A Motor Car” was released as a single from the album, and that out of any of the 14 tracks included within this suite, this is the one that has the most structure to it—like, traditional songwriting structure that is reminiscent of a verse/chorus/verse organization, simply because the song’s melody is similar in specific places, but Buchanan’s writing, even though it can be similar at the beginning of a “verse” or a “chorus,” is unique in each iteration.

Musically, again, “Buy A Motor Car” exists in that uncanny space where it can become difficult to tell if the string plucking that glistens through the song is coming from real violins and violas, or if it is coming from a synthesizer—and it seems strange, for someone like myself who has such an ear for so many details within an album, but Mid Air is simply puzzling in the sense that there is something off about the way the strings sound—a little sharp, maybe, or perhaps just a little artificial. Regardless, the string plucks—real or fake, give the song a bit of a slow-motion bounce that helps propel it forward, as does the fact that the piano chords have more of a forward rhythm to them, rather than the pensive wandering a majority of the other songs have.

“Buy A Motor Car,” lyrically, comes from less of a wistful or lonely place in comparison to the other songs included in this “suite,” and surprisingly, it finds Buchanan honestly more deprecating than anticipated, at least within the first few lines. “Buy a motor car and drive somewhere you believe,” he asks in the opening lyrics. “Far away from me.”

“I am not sure if I am alive,” he continues. “If everything I see live inside of me.”

The effacing tone of the lyrics, in contrast with the arranging, then shifts the further into the song we get. “I want to think you’ve got it made. The birthday candles—the serenade. But all this time, you’re half afraid. Yeah, I know.”

And like so many of the other narratives Buchanan casts across Mid Air, there is no resolve to the story within “Buy A Motor Car”—ending with a passing acknowledgment of somebody’s fear, and then the song’s final notes from the piano and the airy synth accompanying underneath, dissolving into a slow silence.

*

Have you ever been lonely?

And what I have come to realize, especially the more time I spent with Mid Air—specifically the anniversary reissue of the album, is that I somewhat regret my decision to skim through to the final pages of Nileism, and the discovery that the album was, at one point early on, conceived as a “seventeen song suite for piano and vocal,” because, retrospectively speaking, the inclusion of the b-sides recorded during the album’s sessions that are featured within this reissue inadvertently give a small glimpse into what might have been in terms of an alternate tracklist.

However, one of the b-sides, “God is Laughing,” would simply not have worked within the album's context as it is presented now, and it truthfully barely works as an outtake, included within the supplemental material in the reissue. A quiet, tinny drum machine rhythm and a low organ drone run underneath Buchanan’s strummed acoustic guitar, which calls to mind the polarizing acoustic turn he took with the instrumentation on The Blue Nile’s third album, Peace at Last, but here his voice strains in a way—he isn’t struggling to hit the notes. Not really. But just really reaching to deliver the phrases in the way he wants and is unsuccessful at doing so.

And it is the collection’s other actual outtake from Mid Air’s recording that is not only the most impressive, or poignant of the ephemera found on the third and fourth sides to this reissue, but it as fine, if not finer of a song comparatively to the material that made the final running of the album, especially in its latter half.

Have you ever been blue?

“Have You Ever Been Lonely?” asks a question, yes, but within that question, it gets to the heart of Mid Air and the wistful, melancholic longing and loneliness Buchanan has written a majority of these songs from, but it also gets to the heart of that melancholic longing and loneliness that has been present in his work for almost his entire songwriting career.

The song, coming from a similarly pensive and damn near devastating place akin to the album’s titular track, or some of the other songs sequenced early on within Mid Air, is among the most meditative here, though—much more so than Buchanan is in other moments here.

And it is on “Have You Ever Been Lonely” where perhaps Buchanan walks the finest line between all of the emotions he works within, both in his days fronting The Blue Nile, as well as his writing as a solo artist in this one outing he has made. There is a loneliness, of course, which should be apparent from both the song's title and the first few lines. Still, he then begins to move past that, with declarations of love that are both surprisingly earnest and seemingly genuine. However, there is a part of me that is still skeptical within the context—that he is still treading that space, in these assurances, that there is a desperation at their core.

“Have you ever been lonely? Have you ever been blue?,” Buchanan asks in a whisper at the beginning of the song. “Have you ever been sorry, too?” He then more or less answers his own questions—“I have often been lonely. I have always been true. I have often been sorry, too.”

After that come the assurances, delivered in such a heartfelt way that the “you” in this case almost has to believe him—“I know what to do,” he confesses. “We’ll love, and hold each other now. Believe me—I’m caught up in loving you.”

Unlike a number of the songs found within Mid Air, many of which make observations, or ruminate on a past that, despite the pain or sorrow, Buchanan is unable to stop himself from revisiting, there is a fleeting sense of hope in “Have You Ever Been Lonely?,” that, like these memories, is something he is trying, at times desperately, to hang on to—the desperation in the fragility of his voice, quivering with an unabashed honesty while he walks the line between the loneliness and the desperate assurances.

Outside of the two additional, original songs presumably recorded from the sessions for Mid Air, a large portion of the second LP of this reissue is comprised of instrumental versions of five songs from the proper album, and with Buchanan’s vocal tracks missing, while there is a real beauty to them in this form, but there is something about them that becomes a little more saccharine. In the way the notes tumble and swell within both “Two Children” and “My True Country,” or the overall grandeur of “A Movie Magazine,” I couldn’t help but be reminded of the dramatic, sweeping moments within the score to the movie Love, Actually.

*

And there was something, at the end of 2019, when I was first pointed in the direction of The Blue Nile, and Hats, that briefly kept me at arm’s length—it was Buchanan’s voice. In my piece about Hats, perhaps for lack of a better description, I hesitated to refer to his voice as being “different,” because that is not exactly a resounding endorsement; what I ultimately settled on was that it was distinctive—a little fragile, a little off, but also powerful and soulful, and what I eventually came to understand was that you just needed the patience to ease into it, even when it sounds like his voice doesn’t exactly fit within the music the band was playing in 1989.

Well over twenty years after Hats, and eight years after The Blue Nile’s final album, Buchanan as a vocalist is uninterested, or perhaps simply unable to, hide the age in his voice on Mid Air. It’s a little lower, and maybe a little weathered around the edges, but time had been relatively kind to him upon Mid Air’s arrival in 2012.

And there is, and perhaps there always was, a mystique to The Blue Nile—maybe it would have behooved me to sit down and read my copy of Nileism before the release of this reissue and my analysis of it. The mystique, I think, comes from the years of inactivity and presumably the silence in between each of the group’s four albums, as well as the resentment and contention within the trio that, in the end, contributed to the band’s demise following the release of High.

The mystique within the years of inactivity and silence, and Buchanan’s decision to release one solo album, then more or less return to his existence as a reclusive figure within popular music.

Mid Air is such an unassuming album—small, fragmented, hushed, full of such evocative, literate imagery and melancholy. It’s not a depressing album—but a sad one, and in spending so much time with it, upon its tenth anniversary, what I am left wondering is when is the right time, if there even is one, to listen to Mid Air.

What is the right frame of mind to be in when you put it on? Or perhaps, what frame of mind are you okay with finding yourself in, once the record is over.

Given the smaller, quiet nature of the album, my instinct is to say Mid Air is best suited to be listened to late at night—low lights, the score playing just underneath a perhaps whispered, thoughtful conversation with someone you are extremely close to.

Or is it the kind of album to listen to near the end of the afternoon, and into the early evening—perhaps close to the “golden hour,” where you are drenched in the warmth of the setting sun through your kitchen window, tending to the daily minutiae of cutting vegetables for dinner, as these songs bring to mind the fragments, and memories, that you often feel a wistful kind of melancholy over.

As they bring to mind a loneliness, you try your hardest to avoid ruminating on it.

The people, and places, from the past that have slipped through your fingers.

*

Yes, but my lonely is mine.

There is a way that some can embrace a kind of solitude, and I am, admittedly, a little envious of the way some are able to do so.

The way some are comfortable with themselves—comfortable and outwardly confident in being alone, or doing things on their own.

Have you ever been lonely?

And there is, of course, a difference between being lonely, or loneliness, and being, or feeling alone. The feelings never converge, but can overlap in a way—the feelings that begin in not opposing, but different, places before the overlapping occurs.

Out of curiosity, more than anything else, I asked a friend what her experiences, if any, had been with these ideas—of loneliness, and of being alone, or if she agreed that, before they begin to overlap, if there was enough of a distinction between the two.

“I associate loneliness with, like, a disconnection from everyone else,” she told me, then recalled her experiences, and the effort that went into becoming better equipped in being alone, and feeling less lonely in the process. “That feeling of wanting to belong to someone is a sad desperation that I remember really well, and I’m glad it’s behind me.”

Have you ever been blue?

I came to Mid Air a little over two years ago, after looking into what the members of The Blue Nile had gone on to do following the release of High and subsequent falling out with one another—ordering a surprisingly affordable and still sealed copy from an international seller on Discogs. It’s an album that, at the time, four months into the pandemic, I did not spend a lot of time listening to, but as the months turned into a year, and then a year turned into two, I found I thought about it quite regularly—the album’s use of imagery and its somber tone.

And perhaps this reissue found me at not exactly the “right time,” but at a time that is incredibly fitting, or makes the most sense. At the beginning of the year, it was on my list of albums celebrating milestone anniversaries, and while I figured I would be trying to analyze the album itself—for what it is, as a collection of songs that are loosely tied together to make a whole, what I was not anticipating is that I would be doing this within this other conceit, and this would come at a time when I was compelled to look further into the more significant ideas within Mid Air, and within Buchanan’s songwriting output as a whole.

I was not anticipating this idea that I would find myself ruminating on more and more.

I have often been lonely.

Yes, but my lonely is mine.

I famously do not thrive when left alone—or, perhaps, being sent out into the world alone is a more accurate description. Even the relatively simple act of running errands on my own becomes an exercise in managing low-level, yet urgent anxiety that comes from a place that I genuinely do not understand.

But there is a restlessness that also comes from being left alone—often an uncertainty of what, exactly, I should be doing with myself and my time. How many, if any, kindnesses should I extend to myself with that time if I am able. Or how productive should I continue to push myself to be.

And perhaps it truly is the weight of the last two and a half years finally catching up to me, and the way the maintenance of relationships has changed, but there is a distance I can feel, and have felt, that forms between myself and others. A distance brought on by actual, tangible miles, or by time itself, yes, but a figurative distance as well.

I described this to my friend as a curtain—“I often am overcome with this distant feeling,” I told her. “Kind of a disconnection from others, but just this sensation that I am fading away, or there is a curtain between me and someone else that really is preventing any kind of actual interaction.”

Have you ever been lonely?

And it is less of a feeling of wanting to belong to someone that there is a sad desperation in but a wanting to belong. And a disconnection—a barrier that I cannot see but I can almost touch.

Mid Air, and really, even Buchanan’s writing within The Blue Nile, is not depressing, but there is a sadness—melancholic, bittersweet. The desperation in a wanting to belong, or to connect—and the assurances or promises with little if any intention on keeping found within the songs on Hats then becoming slowly fading memories, wistfully gazed upon, from a time that is too personally difficult, or painful, to revisit with any regularity.

The way nostalgia sometimes aches.

Mid Air is not a depressing album, but there is a sadness throughout in the way Buchanan uses and depicts time and memory—and there is an overlap, of course, between those two. Between sadness or a melancholic feeling, and a visceral depression. Similarly to the overlap between feeling alone and loneliness.

Yes, but my lonely is mine.

However, I am uncertain what to do with it—how to draw back the curtain, or prevent this feeling of slowly fading away.

I am reminded of the lyrics to “From A Late Night Train,” which comes at the halfway mark on Hats—“It’s over now. I know it’s over—but I can’t let go.”

Paul Buchanan, at the time of the album’s recording, was not a perfect vocalist, or was intending to record the perfect take for each song. In this context, he doesn’t need to be. He is grappling with these complicated feelings, breathing in and exhaling them into the world, often fragile and hushed.

Mid Air is not a perfect album, but it isn’t trying to be, and it doesn’t need to be. It is a suite, and it hangs in the balance between the beauty and the sorrow that simply comes from being human—a desperate longing, memories, fragments slipping through fingers, and a bittersweet feeling that lingers in the wake of it all.

The 2xLP reissue of Mid Air is available now through Paul Buchanan's webstore.