Priceless Silence - Seven Mary Three's Rock Crown at 25

And if I remember this correctly, on many of those Friday nights, I did not have intention, or a plan, but by Saturday morning, I would have—albeit, an often haphazard or impulsive one.

For about a year and a half, from the very end of 1996 until the autumn of 1998, my father lived in Dubuque, Iowa—a city that, in only a few years, I would wind up moving to when I went to college. And, for that year and a half, for one weekend a month, I had visitation with my father, where he would pick me up on Friday evenings, usually at the McDonald’s in Galena, Illinois—a town a little less than halfway between Dubuque, and the place I grew up, Freeport, Illinois, then returning home on Sunday, mid-morning.

On Saturdays, we often went out to lunch, or occasionally we would see a movie in the early afternoon; and what I remember doing the most on those Saturdays was wandering around the Kennedy Mall, looking for things to spend my allowance on.

I have always been bad with money, and I realize now, as someone on the cusp of 40, that the trouble started when I was very young.

As a kid—like, a very young kid, up until I was 11 or 12, nearly every dollar from my allowance went toward buying comic books, once a week, from the drug store in Freeport on Tuesday afternoons, usually carted down by my mother when she was done with work, or when I would get home from school. It wasn’t until I became a teenager that I quickly drifted away from regularly buying and reading comics. I was much more interested in adding to my growing compact disc collection.

In the mid-1990s, and still, to this day, Dubuque was around double the size of Freeport, but the Kennedy Mall was not very large—not even two levels, but for some reason, from the mid-1990s until 2003, it contained both a Musicland at one end and, again, for some reason, in the food court a Sam Goody—literally the same store, both owned by the parent company—The Musicland Group, Inc., which also owned another staple of shopping malls in the 1990s, Suncoast Entertainment.

As a young teenager, and later, as a college student, I spent a lot of time, and even more of my money, in both Musicland and Sam Goody.

And, unless it was something I could buy at a department store like Wal-Mart or Shop-Ko, Freeport did not have an easily accessible record store when I was a teenager, so on many of those weekend visits with my father during the years he lived in Dubuque, if there was a recently released CD I wanted to look for, or something I had read about in a music magazine, my plan, or intent, was to see if I could find it at either Sam Goody or Musicland.

And there were some weekends when, on Friday evening, as I settled into the guest room of the apartment my father lived in with the woman he recently married, I did not have a plan, or any intent.

I just had money, as it still occasionally does, burning a hole in my wallet.

*

“Records can age like people do. One day you might wake up, look in the mirror, and not like what you see. A few years later, same mirror, same face, and you find something worth loving again. So it goes. Do you ever ask yourself, ‘Are you still you, in there, somewhere?’”

*

And it is something that had, as one might anticipate, taken me quite a long time to realize, but the older I get, the more I can discern, and am often surprised when I do discern, the misogyny and toxic masculinity that has been woven into the lyrics of contemporary popular music—probably often going unnoticed by a majority of listeners.

It would have been when I heard the song “The Distance,” by Cake, maybe four or five years ago playing in the kitchen at work—a song I had heard countless times before when I was a teenager with as ubiquitous as it was at the tail end of 1996. But in hearing it now, I understood the toxic nature of the conceit and could hear the gross desperation in the unwanted advances of the song’s protagonist.

And I hadn’t really thought about the song “Cumbersome” by Seven Mary Three within this kind of a context before. Still, it, too, like countless other songs, is written from a place steeped in a toxic and fragile masculinity—flaunting it within the snarled opening line, “She calls me Goliath and I wear the David mask—I guess the stones are coming to fast for her now,” which are sung as the thesis being the song.

I am uncertain if this is a term that is indicative of a specific era, and is no longer applicable because of how music, as a whole, is released and consumed, but there was a long time when the expression “one-hit wonder” was used to describe a band or artist who saw unprecedented success with one song, then was unable to match, or surpass that level of commercial success with subsequent singles or albums. There are instances of a band or artist that had been deemed a “one-hit wonder” who continues to make music, just on their own terms, often developing a smaller, but devoted base of listeners who were drawn to more than just one popular single.

Conversely, there are instances of a band or artist deemed a “one-hit wonder” who, unable to match or surpass that level of commercial success, folds completely and fades into obscurity.

Until recently, I had not considered the band Seven Mary Three to be “one-hit wonders,” but in even a cursory glance of their trajectory, beginning with the release of their major-label debut, 1995’s American Standard, through The Economy of Sound, released in 2001 and the last record they’d issue via a major label subsidiary. Until their unceremonious split in 2012 following two additional independently released efforts, the group was never able to replicate the success of the single “Cumbersome,” and the album it was lifted from.

But it is also possible, and perhaps implied by members of the band, that after the meteoric rise of the band’s profile, that level of success was something they were not interested in replicating.

*

What I don’t remember if it was in June or July, but it would have been a Friday night, during the summer of 1997, when I was in Dubuque for visitation with my father, and I was up late, hunched at the edge of the bed in his apartment’s spare room, television volume down low enough that I could just barely hear it, watching music videos on The Box.

I grew up in a house that almost always had cable television, but the channels offered in Freeport paled in comparison to what was available through Dubuque’s cable provider at the time—including The Box. The channel was initially launched in 1985, according to Wikipedia, and for its first five years, was a fledgling network based out of Miami. Sold in 1990, a co-founder of MTV and VH-1 was brought in to run and subsequently expand the network's reach.

By 1997, The Box, or at least the programming that aired late in the evening, was entirely comprised of viewer requests. Through a 1-900 number, for prices ranging from .99 to $3.99, you would be prompted to enter the code for which video you wanted to request—and perhaps I am misremembering this, but I thought, at least in 1997, the numerical codes that corresponded to each video available ran as a text scroll on either the top of the bottom of the screen—by the network’s demise in the early 2000s, The Box’s layout became much more elaborate, and per its Wikipedia description, the scroll of numerical codes took up the bottom third of the screen, paired with real-time comments from viewers on each video; the videos themselves were placed in the top left of the screen, while the network’s hotline was displayed in large numbers on the right.

And what I don’t remember is if I had skimmed Rolling Stone’s paltry two-star review of Seven Mary Three’s third album, Rock Crown (stylized as RockCrown) before seeing the video for the album’s single “Make Up Your Mind,” late on a Friday night in either June or July, on The Box, or if it was after I had already bought the album.

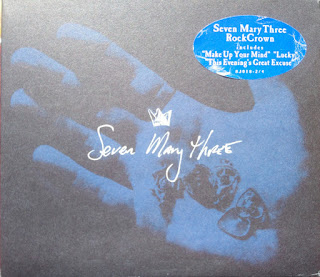

But it was on a Friday night, in either June or July, hunched at the edge of the bed in the spare room of my father’s apartment, that I sat, watching and listening, for all of two minutes and thirty seconds. And perhaps a little haphazardly, and a little impulsively, the following day at the Kennedy Mall, I bought a copy of Rock Crown on CD from Sam Goody—the large yellow sticker, indicating the album’s sale price in red numbers, clinging to the cellophane wrapped around the disc’s thick cardboard slipcase.

*

“Collective Soul, Candlebox, Live, Bush, Seven Mary Three: none of these bands were cutting-edge or underground, and none were consumed, Cobain-like, by the possibility that the wrong sorts of listeners might turn up at their concerts. But all of them provided proof that in the nineties, being in a band that played ‘rock,’ as opposed to some subgenre of it, meant sounding a bit like Nirvana.”

-Kelefa Sanneh, Major Labels: A History of Popular Music in Seven Genres

There are myriad theoretical genres out there. Up until recently, I did not realize that the expression “post-grunge” had been used to describe the crop of bands popping up shortly before Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain died by suicide, or shortly after. “Alternative Rock” was a catch-all descriptor tossed around in the early to mid-1990s that eventually lost its meaning. Still, I can see now, or maybe more accurately, hear now, why a band like Seven Mary Three, inherently a “rock band,” could be called, as they are listed on their Wikipedia page, “post-grunge”—not as earnest and artistically temperamental as Pearl Jam, not as creeping and paranoid as Alice in Chains, not as swooning and psychedelic as Soundgarden, and not as volatile as Nirvana, but borrowing just enough of the sonic elements to keep the idea of “grunge” music alive after the moment had come to an end in 1994.

Named after a reference to the television show “CHiPs,” Seven Mary Three formed in 1992 after Jason Pollack and Jason Ross met in college in Williamsburg, Virginia. Ross and Pollack shared songwriting, with Ross singing lead vocals and playing rhythm guitar, with Polloack playing lead, and contributing backing vocals. The duo filled out to a four-piece with the addition of a bassist, Casey Daniel, and drummer Giti Khalsa. Two years after forming, the band independently released its debut, Churn, and a song from the album—an early iteration of the single “Cumbersome,” began to generate traction through airplay on a hard rock station based out of Orlando, Florida.

The band relocated to Orlando, and their regional success attracted the attention of major labels—in 1995, Seven Mary Three inked a deal with the Atlantic Records subsidiary Mammoth, recording and releasing their major-label debut, American Standard, which featured re-recorded versions of nine songs included initially on Churn. Maligned by critics right from the gate, but regardless, American Standard eventually went platinum within seven months of its release thanks to the success of “Cumbersome,” which peaked at number one on the Billboard Mainstream Rock charts, reached number seven on the Modern Rock Tracks chart, and just barely cracked the Top 40.

In 1998, around a year after the release of Rock Crown, Seven Mary Three issued Orange Ave., which featured “Over Your Shoulder,” a mid-tempo, kind of twangy single that managed to chart relatively well, and the short, wistful ballad “Each Little Mystery,” which, if I remember correctly, found placement in an episode of a teen drama on The W.B.—probably “Dawson’s Creek.” The band’s real final gasp of commercial success came in the summer of 2001 with the bombastic single “Wait,” from their final major-label effort, The Economy of Sound, and had been featured on the soundtrack to the Kristen Dunst vehicle, Crazy/Beautiful.

Before the release of The Economy of Sound, Pollack left the group, and was replaced by Thomas Juliano, and drummer Khalsa departed in 2006. Seven Mary Three released two independent albums in 2004 and 2008, and quietly disbanded in 2012; a year after the breakup, per the little information available via the Seven Mary Three Wikipedia page, Ross was appointed as the head of media and strategic partnerships for The Bowery Presents, in New York.

*

Rock Crown, as an album, can take itself entirely too seriously at times.

In a pull quote from AllMusic’s review of the album, Seven Mary Three is described by a critic as a “horrid” cross between Pearl Jam and Grand Funk Railroad, and that the ambitions to “emulate the sociopolitical issues” found in Springsteen's best material was undone by lackluster guitar work.

And it is, in a sense, the sound of a band trying to come out from its own shadow, only to keep falling back into what it knows, perhaps out of comfort or familiarity.

There’s a quote somewhere, and I don’t remember where I read it now, but it goes on to explain how the band went into the recording of Rock Crown as a response to how quickly mainstream success came for them after the release of American Standard. It isn’t the inverse, or the antithesis of that album, let alone “Cumbersome,” that it often thinks it is. The band—specifically Ross, touts the record as being more in line with the tradition of a “singer/songwriter” or acoustic, folk-rock—something much more introspective. Something that reflected the growth they had experienced as their stock began to rise.

And yes, that is true, but only to an extent. Because in the sense that it is a record that sounds like a band trying to come out from its own shadow, there is a perpetual give and take that occurs throughout. A large portion of the album’s sprawling 15 tracks—primarily found in the first half, are extremely raucous and unhinged in their post-grunge caterwauling and angst.

Upon release, it made for an extremely uneven and frustrating album, but it was compelling. And that’s the thing—it always has been, even with those faults. It is still strange, confusing, but utterly fascinating and daring to hear today.

Running just shy of an hour, a good portion of Rock Crown’s 15 tracks are surprisingly short, e.g., “Make Up Your Mind,” which is barely over two minutes. And within the songs that are this concise, they never feel unfinished, or like they have been rushed. They just do not overstay their welcome.

And that is quite all right in some cases—specifically the songs that are a lot less successfully executed, or the songs that find the band falling right back into the crunchy, electric guitar chugging angst they were trying to get away from.

Rock Crown is a very deliberately paced record—you can almost hear how meticulously sequenced it is while it unravels, built around very clear first, second, and final acts, though almost entirely front-loaded with its most aggressive tracks early on, the uneven nature of the album’s temperament never really impacts how it feels from start to finish. It never really drags, and even when things slow down, the band, to their credit, knows how to build the momentum back up to push it through.

Following a dramatic, sweeping, and slow-burning acoustic opening track, which does kind of set the tone for just how seriously the album will take itself at times, Rock Crown’s titular track, arriving second in the tracklist, begins an explosive, angsty four-song run, with the conclusion of one song often careening into another, or little if any breathing room as one song ends and the next begins.

And it is this run of songs, leading up to the album’s middle act, that walks a fine line between the material on Rock Crown that works—in this case, if you take the songs for what they are—and material that doesn’t land.

I have never really sat down with Rock Crown and listened through an analytical ear before—always just someone who bought the album shortly after it was released, and has managed to carry that album with them, in one way or another, for 25 years. There are times throughout where Ross and Pollack’s lyricism is easier to unpack or decipher than others, but surprisingly, the writing on Rock Crown is shrouded in a lot of fragmented ambiguity, which is, perhaps in part, what makes it still such a compelling listen.

“I haven’t seen a doctor since I can’t remember when,” Ross begins with a guttural ferocity in his voice on “Rock Crown,” a chaotic and frenetic number built around aggressively bashed out percussion and distorted, crunching electric guitars. Later, in the briefest of bridge sections, he howls, “I’m a season in hell, 20 years from showing up.”

Later, on the creeping “Honey of Generation,” there is an unspoken sense of menace that courses through it, as the bassline slithers and a heavily tremoloed guitar quivers. At the same time, Ross continues to shred his larynx, shouting additionally mysterious and vague lyrics—“Liquid used to surround me. My freedom—swimming and drowning. Today we throw it up for sale. Today we’re giving it away,” he barks before the song slams into a hard rock-inspired thrash.

The grungy angst that “Honey of Generation” concludes with segues into the brasher “Home Stretch,” which is Rock Crown’s heaviest moment. Ross, still barking ambiguities, crafts a fascinating, though difficult to unpack narrative within the song’s opening lines: “You in your mother’s new shoes—bet you like them as much as her blues. Don’t tell anyone but I plan to move the first time you look away,” then, later, in what serves as the song’s chorus, though a song like this—and many songs on Rock Crown, seemingly lack the kind of traditional verse/chorus/verse structure, he growls “There’s only one sound to love,” before screaming “Bye-bye, bye-bye, baby goodbye,” a handful of times.

And it is moments like these on Rock Crown that is, perhaps, less about lyrical clarity, writing something infectious and accessible, and more about setting a tone, or creating an atmosphere. And in that sense, the band is doing their job. The first act of the album is dizzying in all of the shifts it makes—sequencing in between the heavier moments is the electrified-country inspired “Needle Can’t Burn (What The Needle Can’t Find),” which is among the most quickly-paced tunes on the album, clipping along with a strong rhythm and a little bit of a twangy edge to both the acoustic guitar and Pollack’s lead playing, as well as in Ross’ vocal delivery.

Among the songs on Rock Crown that aren’t just about “something,” but are about SOMETHING—heavy-handed attempts at writing those mentioned above “sociopolitical issues” into hard rock lyrics. “I don’t want to spend the rest of my life starin’ at a man, looking down a line,” Ross begins humbly on “Needle Can’t Burn.” Then, in the second verse, “I don’t want to spend the rest of my life lookin’ for the words I’m never going to find. You read them in a book and apply them to your life, but now can I be as pretty as she writes?” he asks, then continues to lean into the narrative of a struggling, blue-collar couple as the song progresses. “She don’t want to spend the rest of her heart—waste it on a job, and never get a start,” Ross muses. “Part of her says she should be herself, and part of her says she should be with someone else.”

In the way Rock Crown teeters back and forth between the ambition of what it wants to be, and what it can’t help but fall back on, there are other moments like “Needle Can’t Burn,” musically speaking, where Seven Mary Three push themselves into a particular sonic territory. The twangy, western feeling of “Needle” is the most successful, or the one that perhaps comes the easiest to the group—they try to electrify and amplify the angst in the blues later on in the record with “What Angry Blue,” and a few songs later, a rollicking, folksy, and rootsy stomp on “Player Piano,” both of which are among the album’s weakest contributions.

*

In the way music is primarily consumed now by listeners, the notion of the liner notes, or physical packaging, is an artifact from a different time.

I don’t think I had forgotten this element to Rock Crown—specifically the booklet housed in the CD’s jewel case; I just don’t think I had ever really put it together before, but what I realized in revisiting this album, and everything that comes with it, for its 25th anniversary, are all the similarities—less musically. However, there are some, and more with the way the album is presented through its liner notes, to Better Than Ezra’s second major-label album, Friction, Baby, which was released in the autumn of 1996.

There is a place where the careers of both bands intersect—both, arguably, were on the outskirts of the “alternative rock” movement in the mid-1990s, and had success with singles issued off of their respective major label debuts; both were signed to Warner Brother subsidiary labels (Better Than Ezra, for three albums, was linked to Elektra Records); both acts have a connection to the southern part of the United States; and in a sense, both released third albums via their major label deals that were much less commercially viable than anticipated.

The CD booklets for both Friction, Baby, and Rock Crown are printed on the same kind of cardstock, and both booklets, rather than reprinting the lyrics verbatim, use fragmental phrases throughout, overlaying out of context lyrics on top of extremely “artistic” photographs. There are more photographs of the three members of Better Than Ezra in Fiction, Baby’s booklet, but there is no clear band photograph in Rock Crown. The only real representation of the band finds three of its members sitting on couches in a warmly colored room while, presumably, Ross stands front and center, mid-movement, strumming the acoustic guitar, his face obscured.

And like each band’s connection to the southern portion of the country, both albums were recorded in New Orleans in 1996 in the same recording studio—Kingsway; Friction, Baby for a month in the spring, and Rock Crown in October.

“Recording in New Orleans changed my life,” Ross said recently about Rock Crown. “I can still taste that city on my skin, the kaleidoscope of hidden corners and southern gothic grandeur, the history, camaraderie, and endless opportunity for discovery, the Zydeco cowboys in the woods and brass bands in the streets—goldfish swallowing, indulgent, and otherworldly. I made some lifelong friends. The city showed me a glimpse of its glimmering soul—and laid bare my own.

“My experience there galvanized the way I look at the world, the way I see music, and why I still love whom I love.”

And it is interesting to reflect, even anecdotally, on how both bands used the recording space.

There is a lot more depth, and warmth, to the way Better Than Ezra’s Friction, Baby sounds in comparison to the very flat, early-90s production of Deluxe, which was issued independently in 1993, then rereleased in 1995; Seven Mary Three’s major-label debut, American Standard doesn’t exactly suffer from the same flatness, but the album’s arranging and mixing is far from the more robust sound they gravitated toward in New Orleans.

Outside of incorporating more instrumentation, and slightly more complexities within some of the songs, there is a very raw, organic feeling that runs throughout Rock Crown. And this element in the production—duties shared by Pollack, Ross, and Tom Morris, is maybe not a detail I had ever picked up on totally when listening to the CD in my car stereo as a teenager and into my early 20s, but instead it’s something I was able to discern in listening through headphones this time around, like the tape hiss filling the background of the album’s pensive centerpiece, “Times Like These,” or the, at times, lack of clarity on the way Ross delivers his vocals, or the way the microphone picks up his voice. And it is this kind of minutiae that adds to a sense of urgency within the album—an urgency I can recall hearing when I was younger, and the time I spent with it during my final year in high school, and an urgency that still surges through it today.

*

Within the uneven nature of Rock Crown—the album it thinks it is, or wants to be, and in its inability to escape its nature completely, the album it winds up being regardless of intention, there are very clear glimpses of the inward, folk-leaning, singer/songwriter kind of aesthetic that Ross and the band wanted, or were grasping at, but were not able to use to shape the entire album.

And it is those songs—two of them, specifically, that are similar in their arranging and structure, and another that, even in its unabashed, heart on sleeve, earnestness—all of them found within the album’s second half, have aged the finest, and are among the reasons Rock Crown has stuck with me for as long as it has.

“Gone Away” arrives as the album’s second half begins, following “Make Up Your Mind,” which, in a sense and as best as it is able to, closes out the first portion of Rock Crown. There is a gentleness—almost a whisper, to the way “Gone Away” slowly and gracefully unfolds. It, like so many of Ross and Pollack’s lyrics on the album, operate within an extremely fragmented narrative—there are implications of what a song like this might be about, but there is enough ambiguity within the wistful and reflective nature, so it feels like you are often on the cusp of understanding, or unpacking it more, but it slips away as the song, barely over two minutes, quietly tumbles into a space that connects it to the earnest storytelling of “Times Like These.”

Yes, Ross and Pollack rhyme June with June on “Gone Away.” But I try to be forgiving with this minor detail within the song’s narrative because the rest of the imagery in the song, for as fragmented and dream-like as it can be, is vivid.

“It’s not the clothes that she borrows,” Ross begins, singing much gentler than he does literally anywhere else on the record. “Just call me out, and you know I’ll follow.”

“Sometimes in deep thought, I’m 31,” he continues. “She’s wanting kids—sounds like fun. I’ll teach them to sing along. It sure beats the end of a smoking gun.”

And there is not a violence, per se, that is found within Rock Crown—outside of the caterwauling aggression of the first part of the album and the way Ross pushes his voice into a place of explosive angst. One of the things that have lingered with me, over time, are the instances of violence, or a darkness, referenced in some of the album’s writing.

It happens again in “Times Like These,” where Ross sings, “Got a sheriff’s name branded where I should have kept clean—and if you get too close, you’re gonna know what I mean,”; and again in “I Could Be Wrong,” where it seems, in the loosest way, ties back to the imagery of “Gone Away.” “My good looks won’t save my kids from their dad’s predicament,” it begins. “They won’t see my face like this—see my face as a shadow.”

“Gone Away” is structured around gently brushed percussion and a fragile, kind of bluesy guitar noodling riff that doesn’t exactly lighten the tone set by the song’s writing, but provides as much levity as it is able, especially in the song’s final verse (there is no chorus), where there is a sudden contrast in the depiction of the relationship at the center of its narrative. “I know that god exists because I feel him sometimes when she takes up the sheets or my telephone lines. But, when I’m home, she says, ‘Baby, you’re a lie. You’re not really here—you’ve gone away.’”

Musically, there is a slight playfulness to “I Could Be Wrong,” which slithers through its deeply resonate bassline, and quiet, but impactful jazzy drumming, which creates a tumbling rhythm for interplay between the acoustic guitar strums and reserve found in Pollock’s soloing. There is also the surprising and effective inclusion of a trumpet, which works in tandem with the guitar solo in the center of the tune, as well as punctuating the final lines in some verses and the lyrical pairing that serves as a chorus.

Within the final act of Rock Crown, Ross goes back to that Springsteen-inspired earnestness, though rather than making a statement on the working class, “Houdini’s Angels” is primarily a reflection on the self.

Musically, the song is again, like the most impactful moments on Rock Crown, slower and gentler in its instrumentation, and includes a subtle string accompaniment. And Ross, to his credit as a “rock” singer, tries to find the space between the hushed approach he takes in the second half of the album and the guttural shouting he employs in the earlier tunes.

It works, even though the song itself, lyrically, is incredibly heavy-handed in its messaging.

“Do you think that people get tired of themselves?” he howls in the song’s opening line. “Is that why the t.v.’s on all the time? And it don’t take much to get it right back on track, but it won’t fall from the sky, right into your lap.”

And it is one of the few times on the album where, in the self-reflection being done, Ross is also aware enough of the fame he’s achieved through the band. “If I don’t read what they wrote about me I might turn you on to something I’ve found,” he waxes, then later, perhaps sounding a little more agitated, “If I don’t hear what they whisper about me.”

There is a darkness—it isn’t all that oppressive, but it’s there throughout Rock Crown, but it’s a record I’d never consider bleak. Regardless, it’s on “Houdini’s Angels,” even in how plainly spoken its intention is, it is also the moment on the album where there is a real flash of hopefulness.

*

Unless I am simply not looking hard enough in the corners of the internet, the only version of Seven Mary Three’s “Make Up Your Mind” video I can find looks like absolute shit.

The only version of the video I can find was uploaded to YouTube around seven years ago—and rather than by the band’s former label, or the band themselves, it was done by an average site user. And it’s tough to describe the quality accurately—saying it looks like a photocopy of a photocopy doesn’t take into account just how glitchy and pixelated it seems, and how tinny and flat the audio is.

It looks like it was somehow captured while being played on a computer connected to the internet with a dial-up modem.

The video itself, like many videos from the 1990s, takes place in a grocery store—the camera’s point of view, ever-changing, at times is within the shopping cart, while Jason Ross stars as the clip’s protagonist, literally skulking around the store, at times mouthing the words to the song, following predatorily behind an attractive young woman who is trying to buy her groceries, trying her best to avoid the lecherous gazes of the other customers—all men.

The other members of Seven Mary Three appear in supporting roles, popping up in various places throughout the store.

The female star of the video is dressed like she walked out of the pages of a Delia’s catalog, and Ross, his hair a little shorter than it was a year earlier in the video for “Cumbersome,” is wearing a pair of John Lennon-esque eyeglasses.

And it wasn’t apparent, I don’t think, over the last 25 years, that a song that seems so harmless, like “Make Up Your Mind,” could be considered “toxic” in the way Seven Mary Three depicts the masculinity of its narrative. But in reframing how I have thought about a lot of contemporary popular music from the past (e.g., “Cumbersome”), along with revisiting the video—the video that I, 25 years ago, watched late on a Friday evening from the spare bedroom in my father’s apartment, the problematic nature of it is very apparent.

The video itself takes a whimsical, absurdist turn within its final third, before the build-up and ending of the song, as the woman stops at a display of shower loofahs (of all things) and spends a fair amount of time looking at all of them with indecision—the song’s titular phrase then, becoming a literal thing the people who begin comically gather around her ask—“When you gonna make up your mind?” The video ends with her selecting one, and her surprise from the applause and cheers coming from everyone who has convened nearby to gawk at her.

If the fragile male ego was hurt, or wounded, within the narrative of “Cumbersome,” here, it is less hurt or wounded, and bordering more on entitlement.

Because the song’s lyrics are not reprinted in the liner notes, and the Internet presence of Seven Mary Three is still developing, and because of the production on Ross’ vocals and the way he delivers them, there are specific words that get a little muffled and are subject to being misheard. And the song itself, at all of two and a half minutes, is less about the lyricism, I think, and more about the overall feeling created with the kind of rhythm, and the slight dissonance that rings out in the guitar riff that is repeated throughout.

There’s agreement in deciphering at least the first part of the song’s lyrics—“She says we can’t tell them…She wants up front—I can’t do that.” But there is dissension in the final line of the fragmented second verse. “She’s got backup boyfriend” is clear, but is the mumbled lyric that follows “I’m here” or “I’m him.”

Or does it matter?

Is it the same misogynistic lack of consideration for a woman, regardless of how you hear it?

*

I am uncertain when I began following Seven Mary Three on social media.

Up until their unceremonious split a decade ago, the group maintained a presence on Facebook—it doesn’t take very much time to scroll through and find posts from the fall of 2012, many of them regarding the band’s touring schedule.

No formal announcement about the group’s dissolution was made via social media—if it was, it has been erased, and their Facebook page went seven years without any kind of update, until 2019, when a new profile photo and cover photo were uploaded.

There were, again, no updates until the very end of 2021.

It was then that Jason Ross launched a new website for the band, and began writing a regular newsletter entitled High Shelter. Each edition has a link to stream an unreleased recording, often archival in nature.

“It’s been a while,” Ross’ introduction on the band’s website begins. “While there are no plans for live dates, we are sitting on a ton of music. Some recorded a long time ago, and some recorded days ago. It’s time to share this music, some memories, and ideas.”

There are also the implications the group wants to reissue their studio albums on vinyl and create a new merchandise store—though there has been no update on either of these since December of 2021.

Ross, in his first newsletter, offers a contradictory sentiment to what is implied by the greetings from the website—the new music, recently recorded, is not a return of Seven Mary Three, but of Ross himself returning to songwriting and recording with a new group of collaborators.

There have been 13 newsletters so far—many written as short, wistful, anecdotal essays. The third High Shelter goes into the history of the person who inspired Rock Crown’s smoldering opening track, “Lucky.” It links to a previously unreleased, electric version of the song.

The most recent newsletter is the first of a series that reflects on the 25th anniversary of Rock Crown, and accompanying his initial thoughts on the album reaching this milestone, is an outtake from Kingsway sessions—“The New Blues.” It’s a song that was among the titles handwritten on a setlist featured in the photograph used on the last page of the CD’s liner notes.

It’s one of two songs on the list that did not make it onto the album—the other being “A Little Hard, A Little Late.”

“Records can age like people do. One day you might wake up, look in the mirror, and not like what you see,” Ross writes in the newsletter. “A few years later, same mirror, same face, and you find something worth loving again. So it goes. Do you ever ask yourself, Are you still you, in there, somewhere?”

*

On February 11th, 1963, Sylvia Plath died by suicide.

After suffering through several depressive episodes in her life, and having already made a few attempts at ending her own life, she used dish towels and tape to create seals around the doors between the kitchen in her apartment, and the adjacent room where her children were sleeping.

She turned on the gas to the oven, and placed her head inside, as far as it would go.

Do you see Sylvia in the oven?

In my lifetime, there have been several albums that I have bought, and upon purchase, I didn’t connect with them right away—e.g. Fantastic Planet, by Failure, which I purchased in the spring of 1997, but it wasn’t until the spring of 1998 that I was, perhaps, “ready” for it, or had the patience to sit down with it from start to finish, and have a deeper understanding of it.

It’s now one of my favorite records of all time.

It took a few years for me to find my way further into Rock Crown. Even though I bought it upon its release in the summer of 1997 and also can recall buying Seven Mary Three’s next album, Orange Ave., roughly a year later, the first time I remember connecting with Rock Crown would have been during my last year in high school.

There is nothing quite like Rock Crown’s final track, “Oven,” and I think that’s the point. It was written to be a closing song—not the kind of final track that serves as the last gasp before the record’s conclusion, but rather, the kind that knocks the wind out of you and leaves you speechless in its wake.

It’s the kind of song that found its way onto mix CDs for friends, always tucked near the end of the disc, because it’s the kind of song you want others to hear—and to understand the weight of the same way you do.

Do you see Sylvia in the oven?

And this might be a bit of a reach—not a big one, exactly, but perhaps a reach regardless. Within the larger context of the song, as a whole, I am uncertain still, after all of these years, what the real meaning is, but even in that uncertainty, I remain surprised, and impressed, that there is a good chance part of this song is about Sylvia Plath.

“Do you see Sylvia in the oven,” Ross asks, bellowing the lyrics out over the top of strummed acoustic guitar. “Colossal fact—daddy’s ex don’t let you read. Here’s what she sees…”

The only book of poetry Plath published before her death in 1963 was The Colossus and Other Poems.

There is a memory I have of driving through my old neighborhood, in the Illinois town I grew up in. I would have been 17—behind the wheel of an enormous, dilapidated white mini-van. It’s probably the winter, or at least cold, and after dark, when the song “Oven” comes on over the van’s stereo.

I remember hearing the line, “This Kanas wheat won’t break me, and another drink won’t take me. I can make it if you can,” and the way both Ross and Pollack’s voices blend, produced to sound so raw, and honest, I recall the feeling of frisson I got—and I can recall the way that specific moment in the song moved me to tears.

“Oven,” as a song, bored on being emotionally manipulative in how it just keeps walking the line between drama or at least a theatricality, and unabashed beauty.

I still feel that fission today when I hear the song, and once it arrives at that moment.

Rock Crown isn’t a hopeless album, and there is, of course, that sense of hope—even just a flicker of it, that you can hear in a few songs earlier in “Houdini’s Angels.” But as the album ends, that sense of hope quickly fades into the darkness, and is replaced with a terrible sense of urgency and desperation.

Regardless of if “Oven” really makes use of an allusion to Sylvia Plath, it is here that Pollack and Ross’ lyricism is, unsurprisingly, the most poetic but also the most disjointed in how it crafts a narrative that you are just on the cusp of being able to understand. Still, it continues to evade you, specifically in its depiction of the song’s female protagonist in the second verse: “Was your life one big regret? The smartest man she ever met was not buried—put up on a cross.”

Then, the bridge's bleakness gets the song a little closer to its stirring finale—“She thinks it’s over still if that light won’t go on. There’s no hope in life at all if the oven won’t burn.”

The final lines, delivered with Ross’ guttural howl, are defiant against the odds, but are also rooted in a dare, perhaps out of the desperation—

This Kanas wheat won’t break us. And another drink won’t make us free. The oven’s wide open—hold your breath and see.

And for all of the songs on Rock Crown that barely make it to the three-minute mark, “Oven” sprawl itself out slowly and deliberately over six minutes, with the final two minutes serving as an instrumental resolve to the song, where alongside the acoustic guitar, a piano comes in, and very subtly, an atmospheric orchestral arrangement slides in, and then begins to overtake the way the song is mixed, with the guitar and piano eventually fading into the ether.

*

There was a time when what I wrote wasn’t nearly as complicated as it has gradually become over the last three years.

I don’t think I could go back and find the precise moment when the way I wrote about music began to shift—perhaps there were glimpses of it four or five years back, depending on what I was writing about, and eventually, pieces that are incredibly long and complex, somewhat serious or heavy-handed, often held together by flimsy conceits, broken up into sections that I hope I can pull together in the end, is just how I have come to both think and write about music.

But there was a time when what I wrote wasn’t nearly as complicated, and it would have been during the first two or three years I was regularly writing about music when the length of everything was much more manageable, and the tone was a lot more casual, and at times glib.

Rock Crown wasn’t celebrating any milestone anniversary when I briefly wrote about it in the past—during the summer of 2014, when the album itself was 12 years old.

I had been unceremoniously laid off that summer, and I tried to split all of the time I suddenly had between looking for a new job, and writing.

I don’t remember what prompted me to put something that, in retrospect, is very breezy and kind of sloppy, together about the summer of 1997—about the nostalgia of stores like Sam Goody and Musicland, my father’s apartment, and the Kennedy Mall in Dubuque, watching music videos and happening to catch something that grabs your attention. The piece reflected on a handful of CDs I specifically had bought on weekend visits to Dubuque, like Against The Stars by The Dambuilders, and The Sun is Often Out by Longpigs.

I refer to all three albums as “lost classics.”

The last time I immersed myself in Rock Crown would have been in either 2005 or 2006—it’s such a long album that I would often listen to it from beginning to end as a means of underscoring an hour spent in the car on the four hour drive between Dubuque and Northfield, Minnesota, which is where I relocated to 16 years ago.

I can remember at some point on the stretch of highway 52, maybe a little before hitting Rochester—that feeling of thinking you are close to being finished with your drive and realizing that you still have, like, an hour to go—getting the car up a somewhat steep hill, the late afternoon sun beating down through the windshield, listening to this album with my wife in the car, and perhaps being a little too exuberant or enthusiastic as it played—mouthing the words along, or drumming in time on the steering wheel.

And I remember her surprise, I think, that I had picked something so heavy—like, the first half of the record kind of heavy, to play in the car, but that I had such a connection to it. She said something like, “You really know this album, huh?”

Records age like people do.

I often think about how we take music with us over time—the albums, or artists, that we discover at a specific point in our lives that continue to grow as we do; and the albums, or artists, that we discover at a particular moment that we leave behind, occasionally looking back on them, but we no longer have the connection to them that we once did, for whatever reason.

I have always been bad with money. I’ve spent too much of it on CDs and vinyl records. And I am not able to do it as often as I used to, but throughout college, and well into adulthood, I would try to pair down my CD collection by trading in the ones I was no longer listening to at a second-hand store. And perhaps it’s because the cardboard slipcase is so damaged; perhaps the disc itself isn’t in pristine shape, or that I didn’t think there would be a great trade-in value offered for it, but Rock Crown was never up for consideration as a disc to remove from my collection.

Perhaps it’s because, even though it isn’t an album that I haven’t exactly taken with me through time, or that has grown as I have, it is one that the connection to hasn’t been completely severed, and I still find myself looking back often enough.

Rock Crown is indicative of a moment—for me, I guess more a series of moments. Of the summer of 1997, when I was turning 14, visiting my father once a month while he was living in a city that I would, in only a few years, relocate to. Of the winter of 2000—long, cold, dark nights and the aimless driving around that teenagers are wont to do and the realization of how a song could have such a lasting impact on you.

Of mixes made and the effort to pass that song and that feeling along to another set of ears.

Of letting it fill the space around me and getting me through.

Rock Crown is indicative of a moment—for Seven Mary Three, it was a turning point, taken early on, in their career. It isn’t a “difficult” album, but it is a night and day contrast to the sound of the band leading up to their arrival in New Orleans, in the fall of 1996. Even with all of its flaws, and how uneven and, at times, temperamental it can be, there is still beauty within, and the sheer honesty with which it was made still rings out when it plays 25 years later.

It isn’t a “lost classic.” Not really.

It’s an album I bought on more or less a whim when I was a teenager, but it’s the kind of album that finds you, and continues to find you, when you need it.