Album Review: Lana Del Rey - Chemtrails Over The Country Club

Near the beginning of the new year, on the day that the woman born Elizabeth Grant—known to most as Lana Del Rey—was formally announcing her new album and releasing the titular single off of it, I had a brief discussion with a friend regarding how, going forward, it might be difficult to reconcile Grant’s music with both the persona she has cultivated over nearly a decade, as well as who she really is, deep down, underneath the presumed facade.

Two years ago, when I wrote extensively about Grant’s album, Norman Fucking Rockwell, my favorite record of 2019 and a record I still return to somewhat regularly, I pointed out that Grant, as Lana Del Rey, is not a feminist icon—she never said she was, nor is she really trying to be, and at this time, to my knowledge, the most problematic or even questionable thing she had done in recent memory was become involved with a “hunky cop,” whom she claimed “saw both sides” of things.

Grant is no longer in a relationship with said chiseled police officer, and in the time that has passed since the release of NFR, and in the slow, longer than it probably needed to be roll out to her new full-length, Chemtrails Over The Country Club, Grant found herself in moments where it seemed like it might, going forward, be difficult to separate the art from the artist.

She never said she was a feminist icon—and neither did I. And I never said she wasn’t problematic.

Less than a year ago, Grant announced a new album, slated for a September release (which never materialized.) Within that announcement, she also reflected on her peers, as well as music writers, who take issue with her aesthetic and the implications that she tends to glamorize abusive relationships within her lyrics. The statement, more or less unprovoked in the direction it took, went on to criticize a handful of Top 40 artists for having “number one songs about being sexy, wearing no clothes, fucking, cheating, etc.,” adding that she was fed up with the idea she glamorized abuse when Grant sees herself as a “glamorous person singing about the realities of what we are all now seeing are very prevalent emotionally abusive relationships all over the world.”

The thing that people were very quick to point out in reacting to her diatribe was that the artists she called out by name were nearly all women of color—Beyonce, Nicki Minaj, Cardi B, and Doja Cat, to name a few.

Grant doubled down on her statement shortly there after, cumbersomely clarifying things about it, defending it, and stating that it “says so much more about you” than it did her, that people were making it about race.

In the midst of the pandemic, Grant concluded 2020 by releasing a collection of spoken word poetry—turning up for author events while wearing a mask that would do little, if anything, to protect anyone from dat rona, promising a digitally issued album of holiday tunes and old standards—which never surfaced, and teasing the new album with the slow burning, woozy first single, “Let Me Love You Like a Woman.”

The opening line of the song is, “I come from a small town—how ‘bout you?” Grant, according to her Wikipedia, was born in New York City, though raised in a small upstate town of Lake Placid.

Regardless, there is a fiction, or at the very least, a “creative non-fiction” about the person and the persona of Elizabeth Grant and Lana Del Rey and at a certain point it becomes very difficult to tell where one ends and the other begins.

*

Maybe it’s too easy to say that the cover art to Chemtrails Over The Country Club is the problem, and that if I had known there was going to be a “Target exclusive” edition of the album, pressed onto red vinyl (but of course) with totally different artwork, I would have foregone ordering the album from Grant’s website, and just taken my ass to Target on March 19th, and have possibly been able to….ignore as much as I can the problem the cover art turned into.

What I have gleaned from Grant’s persona as Lana Del Rey is that she wants to project the idea of having a lot of close friends—the alternate cover art to Norman Fucking Rockwell1 sees her outside, dressed in all black, meditating with a group of three friends. I hesitate to say that she needs to be a part of, or travel within, an entourage, but rather, the appearance that these people—her “friends”—are there because they want to be, not because they are window dressings.

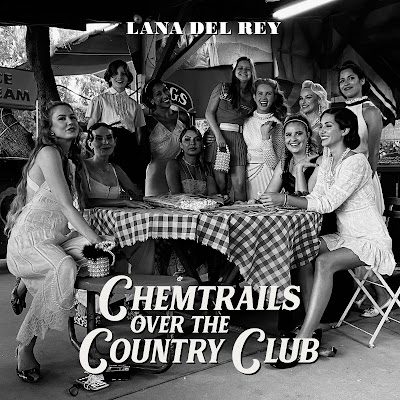

The cover art for Chemtrails is a black and white photo of Grant, flanked by 10 other women, sitting and standing around a table with a checkered cloth draped across the top of it. And outside of being a somewhat strange, or out of place, photo to juxtapose against an album with such a loaded and ironic title, I really saw nothing wrong with it, or did not read into it, until Grant, again totally unprompted, felt the need to return to her controversies surrounding women and race.

“My best friends are rappers and my boyfriends have been rappers,” she said in a statement on Instagram—the kind of tone deaf thing said by someone who probably also at one time has uttered the expression “I don’t mean to sound racist, but…” Nobody, to my knowledge, asked Grant to provide an explanation to the photograph, but she did anyway.

“As it happens, when it comes to my amazing friends and this cover, yes, there are people of color on this record’s picture and that’s all I’ll say about that but thank you,” then adding “We are all a beautiful mix of everything—somer more than others which is visible and celebrated in everything I do. In 11 years working I have always been extremely inclusive without even trying to.”

“So before you make comments again about a WOC/POC issue,” she continued, “I’m not the one storming capital, I’m literally changing the world by putting my life and thoughts and love out there on the table…”

So it’s difficult, as a fan, and a music writer, to not even reconcile with this, but to make any kind of sense of it at all—this unnecessarily confrontational performative allyship that continues to backfire. It’s difficult to separate this, as much as one can, when listening to Chemtrails Over The Country Club, and try to compartmentalize the music as far away as possible from the person making it and the persona performing it. It’s difficult, though not impossible, not to have this inform your listening experience, and subsequent thoughts on the long gestating new record.

Sonically speaking, once again pairing with pop auteur Jack Antonoff, Chemtrails is both a small continuation of the territory explored on Norman Fucking Rockwell, as well as a step inward.

Surprisingly brief—11 tracks, running around 45 minutes in length—overall it’s Grant’s most insular and quiet, and it also finds her moving away from the surprising revelations of its predecessor. Long gone are lyrics like, “You fucked me so good I almost said I love you,” or “If I wasn’t so fucked up I think I’d fuck you all the time”—and instead, Grant operates from a self-aware and borderline dry or humorless place with her lyrics.

She doesn't sound bored with herself, or the persona she’s worked to cultivate and make almost impossible to separate from who Elizabeth Grant is, but from the moment it opens, and even as it heads into its final two tracks, it’s a challenging record that stops short of keeping the listener at an arm’s length, but is also far from welcoming—not as immediate, or personal as Norman Fucking Rockwell, there is a surprising tension, or unease, that serves as a through line on Chemtrails Over The Country Club, and it is a record that, eventually, reveals itself to you, albeit very slowly, and it takes awhile to ease your way into and unpack.

*

Parsing the artist from the art, as best as you can, the first thing that is clear about Chemtrails Over The Country Club, even during my initial run through, is the uneven pacing. Norman Fucking Rockwell, to be fair, was not a perfectly paced or structured record either, especially in its third act, prior to the closing double shot of “Happiness is A Butterfly” and “Hope is A Dangerous Thing For A Woman Like Me to Have.”

Chemtrails is more or less organized by aesthetic, or sonic landscape, gathering the more pensive, piano-based songs and placing them at the top of the record, while the second half heads into the warmth of the late 1960s and 1970s acoustic folk-rock that Grant began developing her penchant for on Lust For Life, but really honed on NFR. And the more times you sit through the record, with the first half being much more accessible, and kind of gently guiding you into to the uneven territory of the latter portion, Chemtrails does wind up working—kind of. Like, it works as best as it can, given all of the things that it, in the end, has playing against it.

The truth is that it would be hard to top Norman Fucking Rockwell, in terms of both the production and arranging from Antonoff, and the very frank, sensually charged lyrics from Grant—the combination, sprawling out across the record’s running time, became a culmination, of sorts, of everything Grant had been working toward as Lana Del Rey—slowly shedding her glitchy, electronic based past, and coming into her own as a confident writer and vocalist.

And I guess that there are moments where the two try to recapture, or in a sense, continue that energy, or feeling—it doesn’t always happen though, but there are a handful of times, specifically in the first half, where they come very, very close.

The reason I say that they come close is because Grant, throughout Chemtrails Over The Country Club is writing from a much less personal place. There’s nothing as tender, or desperate as “Love Song,” or even “Cinnamon Girl”; there’s nothing as blunt and destructive, and uncomfortably funny as “Norman Fucking Rockwell” or “Fuck It, I Love You.”

Chemtrails opens with the simmering “White Dress,” a song that, in places, pushes Grant to the absolute edge of her vocal range and abilities, creating an uneasy sense of dissonance as she sings in a higher, breathy, and truthfully harsher register, causing her voice to crack. But I think that’s the point—to create a sense of tension, and if not tension, a sense of unease, which she’s successful at, as Antonoff’s swirling, dramatic, and cinematic piano spirals around her narrative.

There is a fiction, or at the very least, a “creative non-fiction” about the person and the persona of Elizabeth Grant and Lana Del Rey and at a certain point it becomes very difficult to tell where one ends and the other begins—and Grant steers Chemtrails into that blurry space in-between right out of the gate on “White Dress,” and she sings, “When I was a waitress, wearing a white dress—look how I do this, look how I got this,” sending her voice into a place so fragile it can’t help but begin to break. Then, a few lines later, “Felt like I got this down at the Men in Music Business Conference—down in Orlando, I was only 19.”

“I only mention it ‘cause it was such a scene, and I felt seen,” she continues.

And folks, there is a lot to try and unpack in just those few lines. For starters, I find there to be not so much an irony, but there’s something really fitting about Grant singing the line, “And I felt seen,” considering just how seen (and also attacked) she made me feel throughout a bulk of Norman Fucking Rockwell.

Was Grant ever a waitress, working the night shift, wearing a tight, white dress? Did she attend the “Men in Music” Business Conference in Orlando when she was not even out of her teens?

Is that even a real thing?

Despite the dissonant quality in the way she forces her voice into a range she’s unable to comfortably reach for, there’s something…it isn’t infectious, but the way “White Dress” is arranged, between Antonoff’s instrumentation and even the melody she is singing, it’s a song that lingers well after you have finished listening, leaving you wondering if it’s a song you even really like, or if it’s just spectral enough that it haunts.

Before it ends, and it is surprisingly the longest song on the album (at five and a half minutes), Grant manages to work in a few more lyrics of note—some, a little cringey, like name dropping the Kings of Leon, and saying that she was listening to The White Stripes when they were ‘white hot’; but some are less cringey, and more contemplative and vague—“Summer’s almost gone,” she muses near the end of the song. “We were talkin’ ‘bout life, we were sitting outside till dawn. But I would still go back if I could do it all again, It thought. Because it made me feel like a God.”

For someone who is from the east coast, originally, and currently lives on the west coast, there is a surprising amount of midwestern imagery in the early half of Chemtrails Over The Country Club—in an interview with Antonoff from last fall, she talks about how the midwest inspired a lot of the record, specifically Arkansas and Oklahoma, adding that she “found her heart” there.

The midwestern influence is most apparent in “Tulsa Jesus Freak,” a song that also plays with the religious imagery Grant dabbled in on “White Dress.” And it’s a song where she continues to create a sense of unease, or tension—though it’s not as palpable as it was on the opening track.

Through heavy use of Auto-Tune, and skittering, shuffling, quiet instrumentation, Grant juxtaposes evocative, sensual phrases alongside spirituality, creating a fascinating dichotomy—“You should stay real close to Jesus,” she opens the song with, following it up with “Find your way back to my bed again—sing me like a Bible hymn.”

And it, much like “White Dress,” and much like a bulk of the first half of Chemtrails Over The Country Club, is well written and meticulously arranged in such a way that Grant and Antonoff can write memorable material—here, the Auto-Tuned vocals can get to be a little much, but the melody wastes no time seeping in, and the whooshing theatricality of the song’s big moment, when Grant utters the phrase that was, at one time, the title to both this song and the record way back when it was originally hinted at in 2019, “White Hot Forever.”

Arguably, you could say that Grant has spent a bulk of her career as Lana Del Rey writing what, I guess, I would call the antithesis of a traditional “love song.” Or, at the very least, that is the kind of writing she arrived at throughout Norman Fucking Rockwell. Chemtrails doesn’t backpedal on this exactly, but parts of it are slightly more saccharine than one might anticipate—specifically “Wild at Heart,” overall, one of the album’s gentlest moments.

Grant, as well as literally everyone in contemporary popular music, has never shied away from ablest language, and “Wild at Heart” is no exception as she opts to rhyme the word crazy with lazy in the song’s opening verse—then adding she smokes cigarettes to understand the smog in Los Angeles. It’s also here that she sings the surprising line, “I love you lots, like polka-dots,” which upon my first listen, made me wince, but with each subsequent time through, I’ve come around to the idea of something so cloying being delivered with such earnestness.

In a sense, “Wild at Heart” is almost an inverse of the claustrophobic, desperate tension of “Love Song,” from Norman Fucking Rockwell. There’s even a similar rise in the structure of both the music and the way Grant delivers the lyrics leading up to when the song opens up—a drastic change in structure taking it from being exponentially less gentle and bringing it into that warm, sun drenched, folk rock that, also, shares similarities with the aesthetic found throughout NFR.

Chemtrails’ first side concludes with the aptly titled “Dark But Just A Game,” which is a sharp turn from the reserved arranging of the songs that come before it, and musically, it is the album’s darkest moment, with Antonoff working to create an unnerving, woozy, trip-hop inspired backdrop that underscores Grant’s fragmented lyrics. The title itself, allegedly, comes from something Antonoff uttered to Grant while attending an industry party where, in an interview, Grant states that, “Something happened, kind of like a situation—never meet your idols. And I just thought, ‘It’s interesting that the best musicians end up in such terrible places.’”

It’s eerie and ambiguous, and a little disconcerting with the very vague backstory Grant alludes to, but even with out that, it’s the kind of song that stands out on the record—a slight callback to her earliest material as Lana Del Rey (the Born to Die era), so it musically, and even lyrically with the creeping tautness, is unlike anything else on Chemtrails Over The Country Club.

*

I don’t want to say that Chemtrails Over The Country Club falls apart as it enters its second half, or even that it is unfocused—however, it comes apparent almost immediately that it is lacking the cohesion which held the first portion together, and the restlessness of Grant, as the person and the persona, begins to show.

One of the more surprising things about the album appears in its second half, and that’s the inclusion of a handful of guest artists—Grant is not typically known for playing host to features, save for the stable of marquee names that appeared on Lust for Life. Chemtrails boasts turns from country music singer and songwriter, Nikki Lane, who lends her smoky voice to “Breaking Up Slowly,” while both Zella Day and Natalie Mering (who performs under the moniker Weyes Blood) turn up on the album’s closing track, a cover of the Joni Mitchell song, “For Free.”

Lane’s voice is a stark contrast to that of Grant’s—and it’s Lane’s voice that you hear first on “Breaking Up Slowly,” which took me by surprise during my initial listen. The song is one of the album’s most dramatically paced—deliberate in the structure it is built within, and it’s not nearly as ominous as “Dark But Just A Game,” but there’s still a shadow that is cast over it, specifically in the chord progression. Grant’s voice, taking the second verse, provides a small reprieve from the heavy tone, and the two, when singing together in the refrain, sound incredible in the way that their voices blend.

“Breaking Up Slowly” is one of the better moments in the album’s second half, as is the shuffling, acoustic flourishes and sultry slow burn of “Yosemite,” the one track on Chemtrails that reunites Grant with her pre-Norman Fucking Rockwell writing partner, Rick Nowels—however, it is apparently not a new song, but one written and recorded during the sessions for Lust for Life, and was ultimately scrapped from the album’s sequencing, and one of minor lore among her fanbase.

One would think that including a song written and recorded three or four years before the rest of the album, or at least before a bulk of the album, wouldn’t work in terms of tone and continuity, but because the aesthetic of Chemtrails’ second half is less focused than its first, “Yosemite” actually fits in just fine as the album takes the pivot away from being piano-based.

Maybe you have seen the bumper stickers, or t-shirts, featuring the expression “Not All Those Who Wander are Lost.” It’s the kind of thing I that I, usually, will roll my eyes at, or at least sigh exasperatedly at how insincerely deep or thoughtful it is attempting to be, which is the reason I winced at the use of that expression in a title on Chemtrails Over The Country Club’s tracklist.

Opening the album’s second half, “Wander” is more or less Grant’s attempt at a country song, or at least a song with a little bit of twang included to balance out the whimsical turn it takes in the refrain. Parts of it work, or at least they try, like Grant’s lyrics in the verses, but it’s the repetition of the titular phrase that just does it in, as well as the unnecessary guitar noodling in the song’s instrumental breaks, trying to further cement the country-folk tinge of the song, but it never really connects.

Admittedly, up until I sat down with Norman Fucking Rockwell at a friend’s insistence, I hadn’t given Lana Del Rey much thought, and in going back through her body of work, there are clear moment within songs—specifically on Lust for Life, and near the end of NFR, where Grant, as the songwriter, is incredibly self-aware—but she is aware of the persona, and there is a disconnect, and that self-awareness doesn’t make it all the way through to the person.

Chemtrails’ two least successful tracks arrive at the end—“Dance Till We Die,” and the aforementioned Joni Mitchell cover, “For Free,” with the former becoming self-referential of the latter. “I’m covering Joni and dancing with Joan,” she begins. “Stevie’s calling on the telephone.” And for me, it’s like—okay, I get it. You are a famous singer and songwriter and you have shared a stage with Joan Baez, and had Stevie Nicks as a featured artist on “Beautiful People, Beautiful Problems,” and you have knowingly concluded your album with a Joni Mitchell cover. Regardless of it “Dance Till We Die” was even a good song (it is literally the weakest song on the record, lyrically and musically), the dichotomy of being that self-aware but also that aloof is frustrating.

*

There was a point, probably until I was in either junior high, or high school, that when I’d buy an album—CDs and cassettes at this time—that depending on the album, and my still developing feelings toward it, I might listen to the whole thing, yes, but because I was young and still figuring out “how to listen,” I would mostly spend time with the singles, or the popular songs off of it, forgoing the rest.

So there is a part of me that is mildly remiss to admit that, after working my way through Chemtrails Over The Country Club, I feel like the two finest, or the least flawed, pieces on the album are its two advance singles—“Let Me Love You Like A Woman,” and the title track.

But I say that because they are the two songs that encapsulate what Grant and Antonoff do best, or are most successful at, when collaborating—it’s still out of reach, but tonally, they are the two that almost grasp the feeling and aesthetic of Norman Fucking Rockwell. And that isn’t to say that artists and their collaborators shouldn’t take risks or step outside of “what works,” but throughout an album that appears to be as disjointed as Chemtrails winds up being, these are two small moments of musical stability.

I once read a critique of Lana Del Rey, in her early days, that referred to her as a “torch singer without a flame,” which is an expression I’ve used when describing other artists or albums in the past. There is a—and I don’t want to say a ‘lifelessness’—at times to Grant’s performing, but there is a lack of enthusiasm, or a very deliberately paced and dramatic delivery that it takes time to become accustomed to.

“I come from a small town—how ‘bout you?,’” she asks, her voice low and theatrical at the beginning of “Let Me Love You Like A Woman.” And admittedly, Grant is writing from a much less personally reflective place across the board on this record, but what “Let Me Love You” ends up doing is creating a feeling that is surprisingly easy to be swept up in, which is why it works, whether you really want it to or not.

The love that Grant writes about on Chemtrails is far less desperate, destructive, and tortured (and maybe a little less interesting?) than the love she described on NFR. “I come from a small town—how ‘bout you? I only mention it ‘cause I’m ready to leave L.A. and I want you to come,” she sings, her voice being pulled down slightly by a cavernous reverb that trails each word, giving it a haunted, somber quality, even though it’s not really a haunted kind of song. “Eighty miles north or south will do. I don’t care where as long as you’re with me, and I’m with you.”

“Let Me Love You Like A Woman” is a more traditional love song in the sense that it is not so much a declaration, but a statement, or a yearning for both continuing to build within a relationship as well as to escape. And within the dreamy, swooning atmosphere that slowly casts a spell, it’s easy to overlook that the song, lyrically, ends with the desire to escape—it’s unknown if it ever actually occurs, or if Grant ever does get to love this person “like a woman.” Like a majority of Chemtrails Over The Country Club, there is little, if any, resolution within the song in terms of questions posed but never answered.

Repetition, or the use of recurring themes or phrases is a common artistic device, and even though the “cross references” listed on the Lana Del Rey “fandom wiki” are helpful, you don’t need them to realize there are myriad ideas Grant returns to throughout her canonical works.

One of the lines that still lingers from the end of Norman Fucking Rockwell is, “Don’t ask if I’m happy—you know that I’m not. But at best, I can say I’m not sad.” There is a lot to unpack there, and I’ve spent the last year and a half returning to that idea regularly.

Again, serving as an inverse of sorts, Grant recalls that line slightly, but alters it, both in one of the poems she included in her collection Violet Bent Backwards Over The Grass, and in one of the lyrics to “Chemtrails Over The Country Club.”

“I’m not bored or unhappy,” she muses. “I’m still so strange and wild.”

“Chemtrails” is both unrelenting as it is reserved in the tension it creates. Grant begins singing right from the top, over Antonoff’s gentle piano playing, and it’s that gentleness here, as well as in “Let Me Love You,” that shows the kind of control they both have over the idea of tension and release—and there is no release in either of these songs; the tension created isn’t bad, or unnerving, but it’s there, and difficult not to notice or feel.

“Chemtrails,” out of any song on the album, is probably the most lyrically evocative in terms of Grant not stringing together a narrative with a beginning or end, but working through fragments of imagery—beginning with the title, of course, and the layers to try and work through with the very notion of privilege or feeling care-free, and that being soiled by a conspiracy theory regarding toxic chemicals being dispersed through the air above.

The song also, in one of its lyrics, whether intentional or not, becomes a bit of a conceit for not the album, but for the difficultly one can have, as I have, with separating the art from the artist, or distinguishing the person from the persona—or being completely uncertain where there is a line between the two.

“It’s beautiful, how this deep normality settles down over me,” Grant reflects in the titular track, as a woman born on one coast, residing on the other, but having “found her heart” in the midwest, and with Grant opting, this time, not to write about the volatile love that she found inspirational in the past, Chemtrails Over The Country Club finds her trying to balance the kind of turbulent relationships she has been accused of glamorizing with this quiet desire for normalcy and fondness for a less explosive kind of love and relationship.

At some point in an exchange with a friend of mine—the friend who had suggested I listen to Norman Fucking Rockwell—she referred to Lana Del Rey, or at least the persona of Lana Del Rey, as something to the tune of a “sad white girl on Instagram” aesthetic. And like the balance for what kind of life she wants within the songs she sings, which are probably a reflection, however small, of her own life, Elizabeth Grant and Lana Del Rey are constantly locked in a struggle between how they are and how they want to be perceived. Grant refers to herself as a “glamorous person,” and her demeanor and complete lack of self-awareness would lead one to believe that the “sad white girl on Instagram” projection is not a facade at all, but Grant also, within nearly the same breath, sees herself as some kind of heir to the Laurel Canyon folk-rock movement of the late 1960s and into the 1970s with her inclusion of a similar sound and name dropping Joan Baez and Joni Mitchell.

It seems impossible for her to do both, but she continues to try.

I have no idea how the unneeded controversy Grant stirred around herself and her performative, tone deaf effort to be ‘inclusive’ will impact the arrival of Chemtrails Over The Country Club, or its legacy in her discography. Norman Fucking Rockwell was an incredibly tough act to follow, so it’s practically unfair to compare the two records, and even as different as they are, there are some things between the two that are shared.

Over 5,000 words ago, Chemtrails Over The Country Club was an uneven record that I wasn’t disappointed with, but I was also uncertain just how much I legitimately liked it, and was kind of questioning my decision to hastily place a pre-order for some kind of limited edition colored vinyl variant from Grant’s website. 5,000 words later, it’s still an uneven record—it seems not unfinished, but it’s length does really leave something to be desired, and the lack of cohesion across the structure makes it appear to have been rushed into completion. Uneven yes, but the more time I spent with it and tried to open myself up a little more and as best as I was able to, separate the art from the artist, I was able to find more things about the record that I liked, or at least that I was more okay with.

Chemtrails Over The Country Club isn’t a difficult record, but it’s a puzzling record made by a difficult artist. It isn’t a misstep as an album—Grant, given what she’s put out on social media without a publicist or representative stopping her first—doesn’t need an album to make a misstep with her career or image. It has moments of grandeur and beauty, but it is far less thought provoking than its predecessor and has a partially unfulfilling feeling by the time it reaches its end.

Like the struggle we, as listeners, have with Elizabeth Grant, and Lana Del Rey, with person versus persona and the artist and their art, it’s an album that doesn’t ask a lot of questions, but of the questions it does ask, it provides few answers or any real resolve in the end.

1- This alternative artwork was used, in the end, for the Urban Outfitters “exclusive” edition of the album.

Chemtrails Over The Country Club is out on March 19th via Interscope/Polydor.

Comments

Post a Comment